Will France be the first Western nation to descend into outright civil war between the Left and the forces of sanity? An analysis of the situation.

From The Upheaval

By N.S. LyonsI’ve been keeping an eye on Europe lately, and on France in particular. As I’ve tried to articulate here previously, the era of general upheaval underway is hardly a phenomenon limited to the United States. Instead, propelled everywhere by the same fundamental forces, it appears to be playing out in a more or less similar fashion all across the Western world, and perhaps beyond. In this regard France serves as an especially instructive example, as recent events have served to highlight in striking fashion.

In short, recent national controversy over a pair of open letters directed to the government by a collection of retired and active-duty military officers has not only spawned a month of political controversy in France, but revealed deeper dynamics at work in the country that may help provide a clearer picture of what’s happening everywhere.

On April 21, twenty retired French generals published an open letter to President Emmanuel Macron and the French government in the right-wing magazine Valeurs Actuelles (Today’s Values) denouncing “the disintegration that is affecting our country,” and explaining they were speaking out because “the hour is late, France is in peril, and many mortal dangers threaten her.”

This disintegration, they said, was proceeding as “the Islamist hordes of the banlieue [immigrant heavy city suburbs]” were succeeding in “detaching large parts of the nation and turning them into territory subject to dogmas contrary to our constitution.” For there to “exist any city, any district where the laws of the Republic do not apply,” would soon be fatal, they warned, citing rising crime and the swath of Islamist terror attacks that have struck the country, including the October 2020 beheading of middle-school teacher Samuel Paty by a Chechen refugee that many French viewed as a direct assault on the secular Republic’s deepest values.

However the problem is not only Islamism, the letter writers argued, but “a certain anti-racism” that in reality has “only one goal: to create on our soil a malaise, even a hatred between communities.” The “hateful and fanatical supporters” of this ideology, who “despise our country, its traditions, its culture, and want to see it dissolve by tearing away its past and its history,” might speak in terms of “indigenism and decolonial theories” and make a show of “analyzing centuries old words,” but what they really want is “racial war.”

Meanwhile Macron’s government had used the “forces of order” [the police and military] as “scapegoats” and “auxiliary agents [of state power]” to suppress “French people in yellow vests expressing their despair” – a reference to the huge populist “Yellow Vest” protests against Macron’s economic policies, including higher fuel taxes, that exploded in late 2018.

“Those who lead our country must imperatively find the necessary courage to eradicate these dangers,” they urge, noting that “like us, a great majority of our fellow citizens are fed up with your wavering and guilty silence.” Fortunately, for the most part it would be sufficient a solution to “apply without weakness the laws that already exist.”

But, they grimly conclude, “If nothing is done, laxism will continue to spread inexorably in society, provoking in the end an explosion and the intervention of our active comrades for a dangerous mission to protect our civilizational values… Civil war will break upon this growing chaos, and the deaths, for which you will be responsible, will number among the thousands.”

Initially, the letter was dismissed as mere “eccentric nationalist nostalgia by octogenarian retirees,” as the British Financial Times put it, and the government appeared content to ignore it. The then head of France’s General Directorate for Internal Security, Patrick Calvar, had already warned that France was “on the edge of a civil war” as early as 2016, so this kind of thing was old news. But that changed as soon as Marine Le Pen – the leader of the right-wing Rassemblement National (National Rally) party who polls show is likely to again be Macron’s top rival in presidential elections next year – endorsed the letter, saying “it was the duty of all French patriots, wherever they are from, to rise up to restore – and indeed save – the country.”

Public conversation in France turned to politicization of the armed forces and whether the letter’s final lines were a call for a military coup d'état (the fact that the letter was published on the 60th anniversary of a failed generals’ putsch against President Charles de Gaulle in 1961 providing evidence for this in the view of many). General François Lecointre, armed forces chief of staff, stated that while “at first I said to myself that it wasn’t very significant,” at least 18 active military personnel had been found to have been among the more than 1,500 people who also signed the letter. “That I cannot accept,” he said, because “the neutrality of the armed forces is essential.” They would all be punished, while any of the generals still in the reserves would be forced into full retirement as part of “an exceptional measure, that we will launch immediately at the request of the defense minister.” Still, the government’s ministers emphasized that the signatories were nothing more than an isolated and irrelevant minority in the military.

But soon enough, on May 10, a second letter appeared, again published in Valeurs Actuelles, this time by more than 2,000 serving soldiers writing in support of the first letter’s retired generals, accusing the government of having sullied their reputations when “their only fault is to love their country and to mourn its visible decline.”

They described themselves as being part of the generation that had served abroad in France’s fight against Islamist forces in Mali, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, where they said they have lost comrades who “offered their lives to destroy the Islamism to which you have made concessions on our soil.”

“Almost all of us,” the letter notes, also participated in “Operation Sentinel,” in which troops were deployed throughout Paris following the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo massacre (many armed soldiers still protect sensitive sites, like subways, schools, and synagogues across France), and therefore “have seen with our own eyes the abandoned banlieues... where France means nothing but an object of sarcasm, contempt or even hatred.”

France, they argue, is fast becoming “a failed state”: “We see violence in our towns and villages. We see communitarianism [identity politics, as the French refer to it] taking hold in the public space, in public debate. We see hatred of France and its history becoming the norm.” Their letter, they say, is thus “a professional assessment we are giving, because we have seen this decline in many countries in crisis. It precedes collapse, chaos and violence. And contrary to what [others] say, chaos and violence will not come from military rebellion but from a civil insurrection.”

“We are talking about the survival of our country, the survival of your country,” the letter concludes, addressing Macron. “A civil war is brewing in France and you know it perfectly well.” For if an “insurrection” breaks out “the military will maintain order on its own soil, because it will be asked to. That is the definition of civil war.”

The second letter, this time open to the public to sign, attracted (as of the end of last week) more than 287,000 signatures.

Again came exasperated reactions from many ministers and observers. But what is most remarkable, in my view, is how little enthusiasm most seemed to have for challenging the basic premises of the letters: that France is in a state of growing fracture and even dissolution. Instead, the focus of controversy was once again on the military taking a political position.

Lecointre, the army chief of staff, said those who signed the second letter should quit the armed forces if they wanted to freely express their political opinions, but dropped his previous threats of punishment in a letter to military personnel discussing the controversy. Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire said the letter was “a waste of time and offers no solution,” before adding “yes, there is a political Islamism that is trying to break up the country, and we are fighting it.”

Rachida Dati, Mayor of Paris' 7th arrondissement and another likely future center-right challenger to Macron flatly agreed that “What is written in this letter is a reality… When you have a country plagued by urban guerrilla warfare, when you have a constant and high terrorist threat, when you have increasingly glaring and flagrant inequalities... we cannot say that the country is doing well.”

But perhaps my favorite example was that of (retired) General Jérôme Pellistrandi, chief editor at the magazine Revue Défense Nationale, who prefaced his otherwise sharp criticism of the outspoken soldiers with: “Everyone agrees that society is breaking up, it’s a known fact, but…”

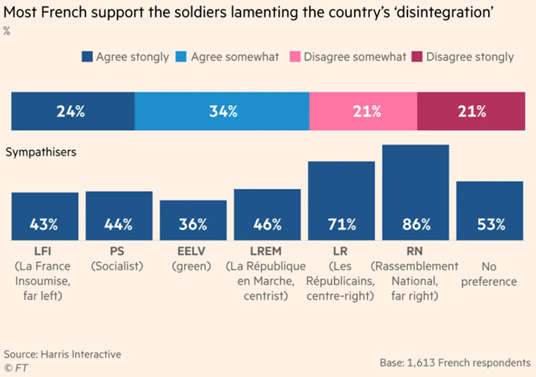

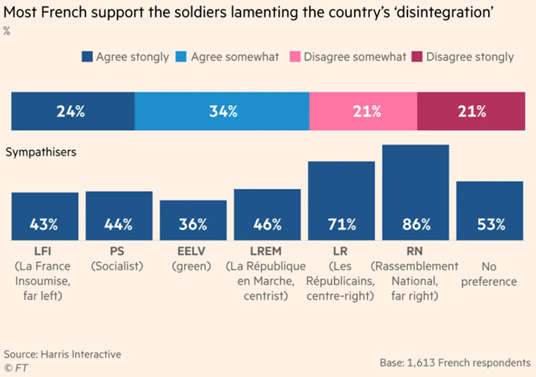

What was going on here? Since when do government officials reflexively agree that their country is falling apart? Well, it turns out that a rather shockingly high proportion of the French public seems to agree with the sentiments the letters expressed. The following chart, created from the results of a Harris Interactive opinion poll taken April 29, after the first letter, is in my view one of the most striking statements about the political mood in a Western country that you’re likely to see for some time:

So, to break this down, not only do 58% of the French public agree with the first letter’s sentiments about the country facing disintegration, but so do nearly half of Macron’s own governing party, the centrist En Marche. Awkward. Nor are those sentiments limited to any one part of the political spectrum, even if the right is more sympathetic overall. Far-left party leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon may have quickly declared that the “mutinous and cowardly” soldiers who signed the letter would all be purged from the army if he were elected, but 43% of his party seem to share their concerns.

But that’s not even the whole of it – an amazing 74% of poll respondents said they thought French society was collapsing, while no less than 45% agreed that France “will soon have a civil war.”

Qui vivra verra…

Several aspects of this whole affair are especially fascinating, from my point of view – and not the talk of a coup, which everyone seems to agree is highly unlikely. Rather, the situation in France says some important things about the nature of the Upheaval that I’m trying to explore here.

The first is simply to demonstrate how the phenomenon is not at all limited to the United States, or even to the “Anglo-Saxon world.” Overall, despite many differences between America and France (e.g. in terms of size, geography, political structures, history, including racial history, language, culture, etc.) the set of simultaneous crises besetting both countries is remarkably similar. Both countries are home to liberal democracies produced by the European Enlightenment, the values of which are now being challenged. Both countries were once largely Christian in moral character – if not in law – but have since been secularized (France earlier), with unpredictable consequences. Both are in the process of coming to terms with a loss of international power and prestige (though this is much more advanced in the French case). Both are obviously influenced by the same technological forces, and by the tide of economic globalization. Both are experiencing growing income inequality, urban vs. rural divides, and distrust of the ruling elites. Both are facing growing social divisions, often along ethnic lines, as well as rising lawlessness. Finally, both are facing major political turmoil over uncontrolled immigration – though the issue lacks the hugely contentious religious aspect in the United States that it does in France.

And, in short, both countries are clearly facing at least one of the defining characteristics of the Upheaval: the collapse of any agreed upon and consistently accepted authority. It is notable that, in both countries (at least until recently) there is only one institution that still garners relatively widespread respect: the military. (And French generals aren’t the only ones trying to capitalize on this with controversial open letters.)

Second, there is the key detail – almost entirely skipped over in the English-language press in favor of focusing on the anti-immigration angle, as far as I’ve seen – of the “anti-racism,” “decolonialism,” and “communitarianism” decried in the two letters as contributing to national dissolution. This is rather unmistakably a reference to the amalgamated, zealously anti-traditional and anti-liberal ideology of the “New Faith” – alternately referred to as Anti-Racism, the Social Justice movement, Critical Theory, identity politics, neo-Marxism, or Wokeness, among other synonymous infamies – that I’ve previously identified as one of the key revolutionary dynamics of our present era.

Let me repeat this proposition again: no revolution has ever remained contained by national borders. The New Faith is a trans-national ideological movement, which can no more remain confined to the United States than it remained confined within the American academy where it matured (it was arguably born in, well… France). And it is more than capable of rapidly adapting itself to and flourishing within whatever national context it penetrates. But, wherever it goes, it’s just as disruptive to the foundations of social and political order.

What’s ironic in this case, however, is that France’s Macron has in fact been one of the only leaders in the West that has clearly recognized this fact and pushed back hard against the New Faith, saying in a 2020 speech for example that “certain social science theories entirely imported from the United States,’’ were prompting ethnic groups to revisit “their identity through a post-colonial or anticolonial discourse.” This, he warned, was aiding and abetting the “conscious, theorized, political-religious project” of “Islamist separatism” in France. The “ethnicization of the social question’’ by American-influenced universities, he claimed in another speech, was in effect “breaking the republic in two.”

Similarly, Marcon’s education minister, Jean-Michel Blanquer, has blamed “an intellectual matrix from American universities” for complicity in excusing and exacerbating Islamist terrorism, and in February the French government announced a commission to investigate the influence within higher education of “Islamo-leftist’’ tendencies that “corrupt society’’ – including by “always looking at everything through the prism of their will to divide, to fracture, to pinpoint the enemy.’’

Meanwhile this has all occurred amid the context of an explosive debate within the French academic world, where (totally unlike in the U.S. and U.K.) the New Faith has faced significant pushback from the establishment elite, with more than 100 prominent scholars banding together to support the government’s inquiry in an open letter decrying theories “transferred from North American campuses,” including the “cancel culture” of radical student activists.

They have popular support: the Harris Interactive poll finds that 74% of the French public think “anti-racist” ideology has only “the opposite effect.” To conceptualize this, one must understand that the French take great pride in their system’s theoretical ability to unite a multitude of diverse ethnic and religious groups under the flag of a single nation. The French state very purposely does not collect or compile racial statistics (doing so is literally illegal) as a function of its liberal commitment to universal rights and treating all citizens equally under the law. It is probably for this reason that Macron has felt emboldened to speak out against America’s ideological invasive species – along with the realization, perhaps, of how absolutely incendiary U.S.-style identity politics was likely to prove in a France already riven with its own social conflicts.

Finally, what’s striking about the situation in France is that every driving factor appears set to only get worse. The COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated the divide between rich and poor; Europe’s economic recovery has been shaky; the ideology of the New Faith is likely to prove more difficult for the French to combat than they expect (the foundation of the established order having been hollowed out over a very long period of time); and the identitarian culture war is likely to only heat up, especially with elections approaching in which Le Pen appears to have a decent chance of actually winning (an outcome that could accelerate political and cultural fracturing, as Donald Trump’s election did in the United States).

In particular, the migration issue is almost guaranteed to only get worse for France. Europe’s declining demographics have created a vacuum that quickly growing populations from impoverished and strife-ridden part of the Middle East and Africa have understandably rushed to fill, and none of these factors have changed. Meanwhile, climate change is likely to rapidly accelerate migration as environmental stressors are expected to hit these regions particularly hard – leading to predictions of a “climate refugee” crisis. Very similar circumstances face the United States, but with Latin America substituting for Africa.

It is notable that every one of these trends, including climate-induced migration, is featured in the U.S. Intelligence Community’s rather ominous recent report evaluating where the world is headed over the next five years, which I’ve written on previously. (Several readers have written to me to criticize my lack of discussion of climate change as a factor in both that post and my essay introducing the Upheaval – well fair enough, though I am uncertain about how much the climate issue has actually driven the turmoil we’re already seeing so far today, as opposed to what we may see in the future.)

France thus seems set to function as an ahead-of-the-curve epicenter for the Upheaval in Europe. No wonder the French are so pessimistic…

In the end, however, I live on the other side of the Atlantic, and have a limited view of what’s going on. If any of you do in fact happen to live in France, or elsewhere in Europe, I’d be particularly interested to hear your thoughts on what’s happening and where you think things are headed – especially if you think I’ve got it all wrong. Go ahead and comment below.

Or, if you’d rather not comment publicly here, please feel free to email me at NSLyons@protonmail.com with your thoughts.

And as always, if you’ve found this interesting, I’d appreciate it if you could share it with others who might as well, and of course remember to subscribe below:

In short, recent national controversy over a pair of open letters directed to the government by a collection of retired and active-duty military officers has not only spawned a month of political controversy in France, but revealed deeper dynamics at work in the country that may help provide a clearer picture of what’s happening everywhere.

On April 21, twenty retired French generals published an open letter to President Emmanuel Macron and the French government in the right-wing magazine Valeurs Actuelles (Today’s Values) denouncing “the disintegration that is affecting our country,” and explaining they were speaking out because “the hour is late, France is in peril, and many mortal dangers threaten her.”

This disintegration, they said, was proceeding as “the Islamist hordes of the banlieue [immigrant heavy city suburbs]” were succeeding in “detaching large parts of the nation and turning them into territory subject to dogmas contrary to our constitution.” For there to “exist any city, any district where the laws of the Republic do not apply,” would soon be fatal, they warned, citing rising crime and the swath of Islamist terror attacks that have struck the country, including the October 2020 beheading of middle-school teacher Samuel Paty by a Chechen refugee that many French viewed as a direct assault on the secular Republic’s deepest values.

However the problem is not only Islamism, the letter writers argued, but “a certain anti-racism” that in reality has “only one goal: to create on our soil a malaise, even a hatred between communities.” The “hateful and fanatical supporters” of this ideology, who “despise our country, its traditions, its culture, and want to see it dissolve by tearing away its past and its history,” might speak in terms of “indigenism and decolonial theories” and make a show of “analyzing centuries old words,” but what they really want is “racial war.”

Meanwhile Macron’s government had used the “forces of order” [the police and military] as “scapegoats” and “auxiliary agents [of state power]” to suppress “French people in yellow vests expressing their despair” – a reference to the huge populist “Yellow Vest” protests against Macron’s economic policies, including higher fuel taxes, that exploded in late 2018.

“Those who lead our country must imperatively find the necessary courage to eradicate these dangers,” they urge, noting that “like us, a great majority of our fellow citizens are fed up with your wavering and guilty silence.” Fortunately, for the most part it would be sufficient a solution to “apply without weakness the laws that already exist.”

But, they grimly conclude, “If nothing is done, laxism will continue to spread inexorably in society, provoking in the end an explosion and the intervention of our active comrades for a dangerous mission to protect our civilizational values… Civil war will break upon this growing chaos, and the deaths, for which you will be responsible, will number among the thousands.”

Initially, the letter was dismissed as mere “eccentric nationalist nostalgia by octogenarian retirees,” as the British Financial Times put it, and the government appeared content to ignore it. The then head of France’s General Directorate for Internal Security, Patrick Calvar, had already warned that France was “on the edge of a civil war” as early as 2016, so this kind of thing was old news. But that changed as soon as Marine Le Pen – the leader of the right-wing Rassemblement National (National Rally) party who polls show is likely to again be Macron’s top rival in presidential elections next year – endorsed the letter, saying “it was the duty of all French patriots, wherever they are from, to rise up to restore – and indeed save – the country.”

Public conversation in France turned to politicization of the armed forces and whether the letter’s final lines were a call for a military coup d'état (the fact that the letter was published on the 60th anniversary of a failed generals’ putsch against President Charles de Gaulle in 1961 providing evidence for this in the view of many). General François Lecointre, armed forces chief of staff, stated that while “at first I said to myself that it wasn’t very significant,” at least 18 active military personnel had been found to have been among the more than 1,500 people who also signed the letter. “That I cannot accept,” he said, because “the neutrality of the armed forces is essential.” They would all be punished, while any of the generals still in the reserves would be forced into full retirement as part of “an exceptional measure, that we will launch immediately at the request of the defense minister.” Still, the government’s ministers emphasized that the signatories were nothing more than an isolated and irrelevant minority in the military.

But soon enough, on May 10, a second letter appeared, again published in Valeurs Actuelles, this time by more than 2,000 serving soldiers writing in support of the first letter’s retired generals, accusing the government of having sullied their reputations when “their only fault is to love their country and to mourn its visible decline.”

They described themselves as being part of the generation that had served abroad in France’s fight against Islamist forces in Mali, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, where they said they have lost comrades who “offered their lives to destroy the Islamism to which you have made concessions on our soil.”

“Almost all of us,” the letter notes, also participated in “Operation Sentinel,” in which troops were deployed throughout Paris following the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo massacre (many armed soldiers still protect sensitive sites, like subways, schools, and synagogues across France), and therefore “have seen with our own eyes the abandoned banlieues... where France means nothing but an object of sarcasm, contempt or even hatred.”

France, they argue, is fast becoming “a failed state”: “We see violence in our towns and villages. We see communitarianism [identity politics, as the French refer to it] taking hold in the public space, in public debate. We see hatred of France and its history becoming the norm.” Their letter, they say, is thus “a professional assessment we are giving, because we have seen this decline in many countries in crisis. It precedes collapse, chaos and violence. And contrary to what [others] say, chaos and violence will not come from military rebellion but from a civil insurrection.”

“We are talking about the survival of our country, the survival of your country,” the letter concludes, addressing Macron. “A civil war is brewing in France and you know it perfectly well.” For if an “insurrection” breaks out “the military will maintain order on its own soil, because it will be asked to. That is the definition of civil war.”

The second letter, this time open to the public to sign, attracted (as of the end of last week) more than 287,000 signatures.

Again came exasperated reactions from many ministers and observers. But what is most remarkable, in my view, is how little enthusiasm most seemed to have for challenging the basic premises of the letters: that France is in a state of growing fracture and even dissolution. Instead, the focus of controversy was once again on the military taking a political position.

Lecointre, the army chief of staff, said those who signed the second letter should quit the armed forces if they wanted to freely express their political opinions, but dropped his previous threats of punishment in a letter to military personnel discussing the controversy. Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire said the letter was “a waste of time and offers no solution,” before adding “yes, there is a political Islamism that is trying to break up the country, and we are fighting it.”

Rachida Dati, Mayor of Paris' 7th arrondissement and another likely future center-right challenger to Macron flatly agreed that “What is written in this letter is a reality… When you have a country plagued by urban guerrilla warfare, when you have a constant and high terrorist threat, when you have increasingly glaring and flagrant inequalities... we cannot say that the country is doing well.”

But perhaps my favorite example was that of (retired) General Jérôme Pellistrandi, chief editor at the magazine Revue Défense Nationale, who prefaced his otherwise sharp criticism of the outspoken soldiers with: “Everyone agrees that society is breaking up, it’s a known fact, but…”

What was going on here? Since when do government officials reflexively agree that their country is falling apart? Well, it turns out that a rather shockingly high proportion of the French public seems to agree with the sentiments the letters expressed. The following chart, created from the results of a Harris Interactive opinion poll taken April 29, after the first letter, is in my view one of the most striking statements about the political mood in a Western country that you’re likely to see for some time:

Copyright: Financial Times

So, to break this down, not only do 58% of the French public agree with the first letter’s sentiments about the country facing disintegration, but so do nearly half of Macron’s own governing party, the centrist En Marche. Awkward. Nor are those sentiments limited to any one part of the political spectrum, even if the right is more sympathetic overall. Far-left party leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon may have quickly declared that the “mutinous and cowardly” soldiers who signed the letter would all be purged from the army if he were elected, but 43% of his party seem to share their concerns.

But that’s not even the whole of it – an amazing 74% of poll respondents said they thought French society was collapsing, while no less than 45% agreed that France “will soon have a civil war.”

Qui vivra verra…

Several aspects of this whole affair are especially fascinating, from my point of view – and not the talk of a coup, which everyone seems to agree is highly unlikely. Rather, the situation in France says some important things about the nature of the Upheaval that I’m trying to explore here.

The first is simply to demonstrate how the phenomenon is not at all limited to the United States, or even to the “Anglo-Saxon world.” Overall, despite many differences between America and France (e.g. in terms of size, geography, political structures, history, including racial history, language, culture, etc.) the set of simultaneous crises besetting both countries is remarkably similar. Both countries are home to liberal democracies produced by the European Enlightenment, the values of which are now being challenged. Both countries were once largely Christian in moral character – if not in law – but have since been secularized (France earlier), with unpredictable consequences. Both are in the process of coming to terms with a loss of international power and prestige (though this is much more advanced in the French case). Both are obviously influenced by the same technological forces, and by the tide of economic globalization. Both are experiencing growing income inequality, urban vs. rural divides, and distrust of the ruling elites. Both are facing growing social divisions, often along ethnic lines, as well as rising lawlessness. Finally, both are facing major political turmoil over uncontrolled immigration – though the issue lacks the hugely contentious religious aspect in the United States that it does in France.

And, in short, both countries are clearly facing at least one of the defining characteristics of the Upheaval: the collapse of any agreed upon and consistently accepted authority. It is notable that, in both countries (at least until recently) there is only one institution that still garners relatively widespread respect: the military. (And French generals aren’t the only ones trying to capitalize on this with controversial open letters.)

Second, there is the key detail – almost entirely skipped over in the English-language press in favor of focusing on the anti-immigration angle, as far as I’ve seen – of the “anti-racism,” “decolonialism,” and “communitarianism” decried in the two letters as contributing to national dissolution. This is rather unmistakably a reference to the amalgamated, zealously anti-traditional and anti-liberal ideology of the “New Faith” – alternately referred to as Anti-Racism, the Social Justice movement, Critical Theory, identity politics, neo-Marxism, or Wokeness, among other synonymous infamies – that I’ve previously identified as one of the key revolutionary dynamics of our present era.

Let me repeat this proposition again: no revolution has ever remained contained by national borders. The New Faith is a trans-national ideological movement, which can no more remain confined to the United States than it remained confined within the American academy where it matured (it was arguably born in, well… France). And it is more than capable of rapidly adapting itself to and flourishing within whatever national context it penetrates. But, wherever it goes, it’s just as disruptive to the foundations of social and political order.

What’s ironic in this case, however, is that France’s Macron has in fact been one of the only leaders in the West that has clearly recognized this fact and pushed back hard against the New Faith, saying in a 2020 speech for example that “certain social science theories entirely imported from the United States,’’ were prompting ethnic groups to revisit “their identity through a post-colonial or anticolonial discourse.” This, he warned, was aiding and abetting the “conscious, theorized, political-religious project” of “Islamist separatism” in France. The “ethnicization of the social question’’ by American-influenced universities, he claimed in another speech, was in effect “breaking the republic in two.”

Similarly, Marcon’s education minister, Jean-Michel Blanquer, has blamed “an intellectual matrix from American universities” for complicity in excusing and exacerbating Islamist terrorism, and in February the French government announced a commission to investigate the influence within higher education of “Islamo-leftist’’ tendencies that “corrupt society’’ – including by “always looking at everything through the prism of their will to divide, to fracture, to pinpoint the enemy.’’

Meanwhile this has all occurred amid the context of an explosive debate within the French academic world, where (totally unlike in the U.S. and U.K.) the New Faith has faced significant pushback from the establishment elite, with more than 100 prominent scholars banding together to support the government’s inquiry in an open letter decrying theories “transferred from North American campuses,” including the “cancel culture” of radical student activists.

They have popular support: the Harris Interactive poll finds that 74% of the French public think “anti-racist” ideology has only “the opposite effect.” To conceptualize this, one must understand that the French take great pride in their system’s theoretical ability to unite a multitude of diverse ethnic and religious groups under the flag of a single nation. The French state very purposely does not collect or compile racial statistics (doing so is literally illegal) as a function of its liberal commitment to universal rights and treating all citizens equally under the law. It is probably for this reason that Macron has felt emboldened to speak out against America’s ideological invasive species – along with the realization, perhaps, of how absolutely incendiary U.S.-style identity politics was likely to prove in a France already riven with its own social conflicts.

Finally, what’s striking about the situation in France is that every driving factor appears set to only get worse. The COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated the divide between rich and poor; Europe’s economic recovery has been shaky; the ideology of the New Faith is likely to prove more difficult for the French to combat than they expect (the foundation of the established order having been hollowed out over a very long period of time); and the identitarian culture war is likely to only heat up, especially with elections approaching in which Le Pen appears to have a decent chance of actually winning (an outcome that could accelerate political and cultural fracturing, as Donald Trump’s election did in the United States).

In particular, the migration issue is almost guaranteed to only get worse for France. Europe’s declining demographics have created a vacuum that quickly growing populations from impoverished and strife-ridden part of the Middle East and Africa have understandably rushed to fill, and none of these factors have changed. Meanwhile, climate change is likely to rapidly accelerate migration as environmental stressors are expected to hit these regions particularly hard – leading to predictions of a “climate refugee” crisis. Very similar circumstances face the United States, but with Latin America substituting for Africa.

It is notable that every one of these trends, including climate-induced migration, is featured in the U.S. Intelligence Community’s rather ominous recent report evaluating where the world is headed over the next five years, which I’ve written on previously. (Several readers have written to me to criticize my lack of discussion of climate change as a factor in both that post and my essay introducing the Upheaval – well fair enough, though I am uncertain about how much the climate issue has actually driven the turmoil we’re already seeing so far today, as opposed to what we may see in the future.)

France thus seems set to function as an ahead-of-the-curve epicenter for the Upheaval in Europe. No wonder the French are so pessimistic…

In the end, however, I live on the other side of the Atlantic, and have a limited view of what’s going on. If any of you do in fact happen to live in France, or elsewhere in Europe, I’d be particularly interested to hear your thoughts on what’s happening and where you think things are headed – especially if you think I’ve got it all wrong. Go ahead and comment below.

Or, if you’d rather not comment publicly here, please feel free to email me at NSLyons@protonmail.com with your thoughts.

And as always, if you’ve found this interesting, I’d appreciate it if you could share it with others who might as well, and of course remember to subscribe below:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.