One friend of mine asked another friend of mine a question, and this is the answer.

From Ko-Fi

By Hilary White

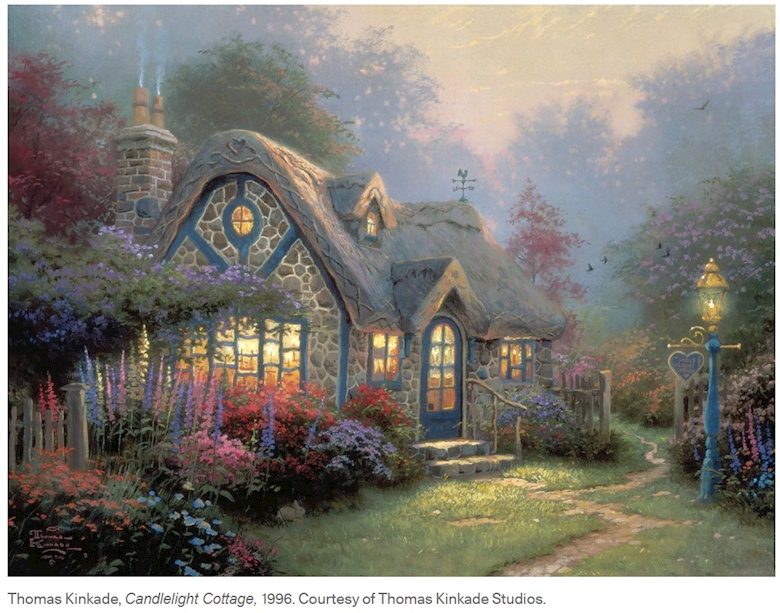

Someone on Twitter asked me an interesting question: what do I think of Thomas Kinkade? My short answer is that it's bad to create bad art to dupe and fleece innocent and good people. To use your knowledge and abilities for evil; to cynically use the honest moral, cultural and political aspirations of simple people for cash.

I gave the short answer yesterday, but then thought about it more. I found this video, and while I was watching it found I was growing really angry. Then I started wondering why. Why did this man and his work make me angry? It wasn't for the same reasons the people in the video were saying. It had nothing to do with the political narrative Kinkade himself used to market his products.

It's not because of the heavy-handed, Disneyfied romanticism. It's not because of the garish palette. Those are just issues of personal taste. I realised I was actually offended by his work, morally. It's not because it's kitsch. It's because it's cynical, exploitative kitsch.

I thought about it and realised there is more to it than just politics. Kinkade was selling a counterfeit of the Real, to assuage the emotional distress caused by the cultural and visual ugliness of our time. He touted himself as a moral opponent of the cynical shysters of the elite art world and made millions selling a blatantly false, synthetic replacement for reality.

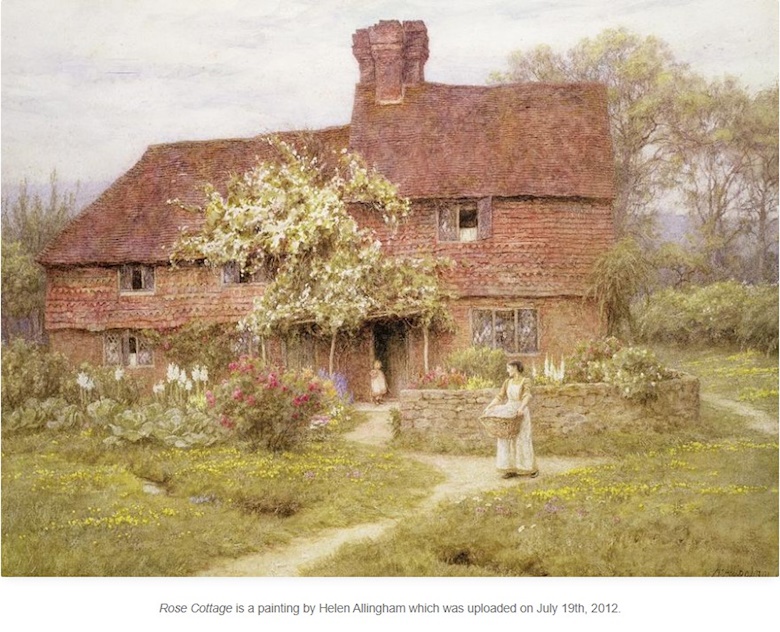

I think it would be useful to compare Kinkade's paintings with those of Helen Allingham, an English watercolourist whose best known work is paintings of country cottages and rural scenes of the end of the 19th century.

The curator of the exhibition says Allingham's work reached peak popularity at the end of the 19th century, offering a curative answer to modernity's anxiety over the growth of stark ugliness in their own urban environments and in art.

"Her works continue to offer everyone a reassuring and nostalgic vision of England."

This scene, while heavily romanticised, is real. This kind of life was really lived by real people, and was well within living memory when I was a child (my grandmother - who had much to do with the raising of me - was born in 1903 and my grandfather in 1897). It is a kind of symbol of a cultural reality in which many people still alive today actually grew up. Including me. In fact, it looks very much like the Victoria I grew up in, populated by elderly ladies of Allingham's own generation who tended gardens that looked exactly like this.

The main difference between Kinkade's and Allingham's country cottages - and indeed the whole genre that includes many beloved children's book illustrators from Beatrix Potter to Tasha Tudor - is truth. Allingham's scenes of rural late 19th century England were painted from life. This was a depiction of the real world - admittedly through a particular lens - that she actually saw and knew. And it shows. However romanticised they might be - and they certainly were that even in her own time - they show an idealised reality as she was actually observing it in real life.

He is the difference between an organic farmer trying to revive healthier eating habits of a previous era, and the corner drug dealer - both want you to feel better...

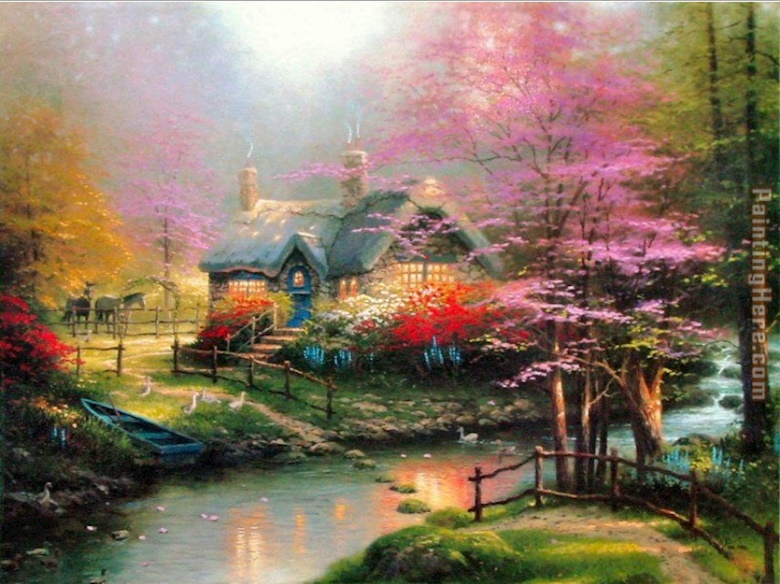

He is the difference between an organic farmer trying to revive healthier eating habits of a previous era, and the corner drug dealer - both want you to feel better... What was Kinkade producing? Cottages that were obviously consciously modelled on the same romantic vision, but so grossly exaggerated and falsified as to be almost parodic, entirely severed from their real-world origins. He was cashing in on the same cultural hunger that gave Allingham success but he was selling a kind of weaponised, synthetic version of her vision, with an underlying malice and obvious ruthlessness that he never did much to hide.

He capitalised on a terrible multi-generational corruption of social culture and the immense century-old deficit of technical training and skill in the art world. By training he had been an illustrator of middling ability who found a formula that he could sell and then stopped dead in his own development. And it is his cynicism toward his own work that is revealing. If anything, Kinkade's work eventually deteriorated into truly un-conscionable levels of emotivist exploitation; from perhaps-excusable kitsch...

At this point, one wonders why we even bother critiquing...

At this point, one wonders why we even bother critiquing...... to outright nauseating schlock to make even the most Disney-Princess-obsessed six year old scrinch up her nose in distaste.

He found a gap and exploited it

His real "talent" was in using an existing political and cultural division, fanning the flames of social discourse, to cash in. And to the tune of (I was shocked to learn) hundreds of millions of dollars. He was, essentially, a cynically exploitative parasite on the American culture wars of the 1980s and '90s.

Kinkade's "genius" wasn't in his painting; it was in his ability to use the degeneration of art in our time - and the political narrative that surrounds it - to sell his brand of snake oil. He knew his mediocre skills as illustrator were more than sufficient to wow his target market - people three or four generations removed from the time when the ordinary skill of drawing was a normal part of primary education and everyone had at least a basic familiarity with art.

The total blackout in the art world over the last hundred years of ordinary technical skills (drawing is NEVER taught now, even in university or other academic art schools) has created wide openings for such people to exploit, even if they are possessed of a skill level that would have got them ignored by the art world of the 19th century. You don't have to have a lot of technical training to really impress modern people - who think the ability to draw is a kind of magic Harry Potter wizard-gene granted by heaven only to a special few.

In other words, Kinkade proved that to clean up as a "genius" with "massive talent" is a matter more of cunning and lack of conscience than artistic ability.

Why does he make me angry? Because it's nasty to be lied to.

It did indeed make me angry, so much so that I had to turn it off half way. And I was surprised by my own passion - I didn't realise how much I disliked the man until I learned more about him.

The over-the-top hyperbole from the New York elites against Kinkade in that video is not artistic but political: of the same kind and from the same ideological source that produced Trump Derangement Syndrome - the Left's lack of self-awareness, mostly. And of course their criticisms were so off target that they only served to make his point; "I'm hated by morally degenerate New York elites? All to the good... Ka-CHING!$$$"

But I'm not on the Left, and I don't despise the people who bought his products. In fact, I rather prefer the company of the countrified, gun-toting, farming class "deplorables" to nearly any other category of person, and have done my own years of railing against the morally degenerate city elites. I don't think it's "stupid art for stupid people". I think it's bad art for people desperate for something really good, but who have been deprived and starved for it.

But tribalism is not what this is about. It was Kinkade himself that made it about tribes. Kinkade did politicise his work, quite deliberately, as a way of corralling his target market, consciously using the political and moral arguments of the time to ensure loyalty to his brand: "If you don't buy not only my work but my hyperbole about it you're fuelling the satanic modern elitist anti-culture."

If you're producing bad art and people are buying it, more power to you; but if you're using a deliberate web of trickery to create and capitalise on social division, you're a narcissistic grifter - and of the particularly nasty, slimy kind who likes to dupe old widows out of their life savings.

And because only the Real counts

Thomas Kinkade died in 2012 of "acute intoxication" from over use of alcohol and diazepam. He left a wife and a mistress to wrangle over his fortune. An ugly end to a man whose reputation was built offering a Disneyfied version of a Christian moral crusade. (And maybe this would be a moment to offer a prayer for the repose of his soul - something he won't get from his Evangelical followers.)

It's worth noting, perhaps, that in his youth he had been a friend and collaborator with another one of my favourite illustrators, James Gurney, with whom he created a handbook on sketching.

But I think it is also noteworthy that his "painter of light" persona came forth after a stint working with the disgusting animation pornographer, Ralph Bakshi:

The success of the book led them both to Ralph Bakshi Studios where they created background art for the 1983 animated feature film Fire and Ice. While working on the film, Kinkade began to explore the depiction of light and of imagined worlds.

After the film, Kinkade earned his living as a painter, selling his originals in galleries throughout California.

In defence of real kitsch

I don't actually have the least beef with "kitsch". The people who bought his work probably really liked it. It's not helpful to just be a snob. We can just let people like what they like, remembering there is plenty of criticism for everyone. I think the urge to despise people who like simple things is a temptation to pride that people can fall into from any end of the political spectrum. And its only too common to accuse anyone who likes beautiful things - including medieval and Renaissance sacred art - of being an unsophisticated rube.

I like simple old fashioned things. I was raised on Beatrix Potter and the EH Shepherd (that is, English) version of Pooh and Christopher Robin.

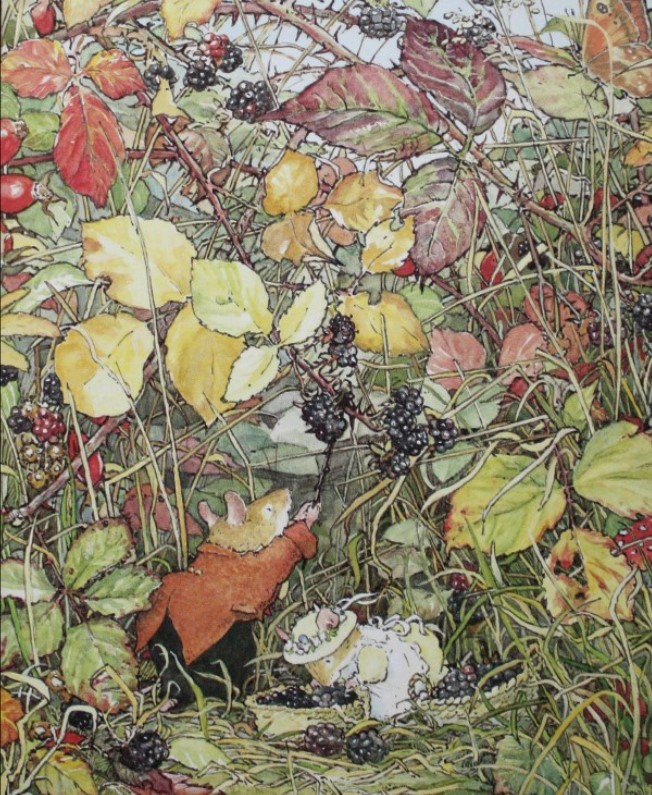

As an adult I especially love Jill Barklem's "Brambly Hedge" children's book illustrations. I've got a collection of Brambly Hedge stories, and even have a little print of one of the paintings on my wall, that I rather treasure.

The real difference, I think, between what Allingham and Kinkade offered is the former's devotion to the Real above the feelings it gives you. Obviously she wanted to sell her paintings, but she was offering something real, if a bit nostalgic and romanticised, that meant something serious to her. It's the difference between a hearty meal of good food and a drug.

Thomas Kinkade devoted his life's work to ruthlessly exploiting the sadness and misery of the modern world - using an ongoing political and cultural struggle to enrich himself - without being willing to do the extra work to actually alleviate it. Without, in fact, devoting himself to anything but himself.

His work was simplistic, formulaic to the point of being indistinguishable from one piece to the next. He made no personal sacrifice to develop as an artist, to devote himself to anything outside himself, or to fulfil any real cultural "nutritional" need.

He didn't work to revive anything, preserve anything or develop anything. He didn't study anything or discover anything. He didn't seem to love anything he was painting about. He didn't go to any effort to learn about and present 19th century rural vernacular architecture (a critical eye on his "cottages" will reveal them to often have been tarted-up versions of suburban American McMansions as much a product of the mass-production culture as his paintings). He didn't bother his head about botanical accuracy - all his gardens are fuzzed-out decorative blurs. He presented himself as "the painter of light" without apparently having the slightest interest in depicting light in reality (hint: it doesn't come from every direction at once.) He championed nothing in his life's work but himself.

There are many ways in which his work reminds me of a drug, but the main one is that it offered a counterfeit, a replacement, of the kind of joy-in-the-real people are so desperately wanting.

***

Great thanks to all who have followed this page, and who have kindly helped with donations. If you like, leave a comment and we can talk. If you have enjoyed this and other articles, please consider donating through the page button below, or using my external PayPal, here.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.