From Bitter Winter

By Ruth Ingram

Ninety years ago today, the first 20th century Uyghur Christian martyr was slain for his faith in East Turkestan.

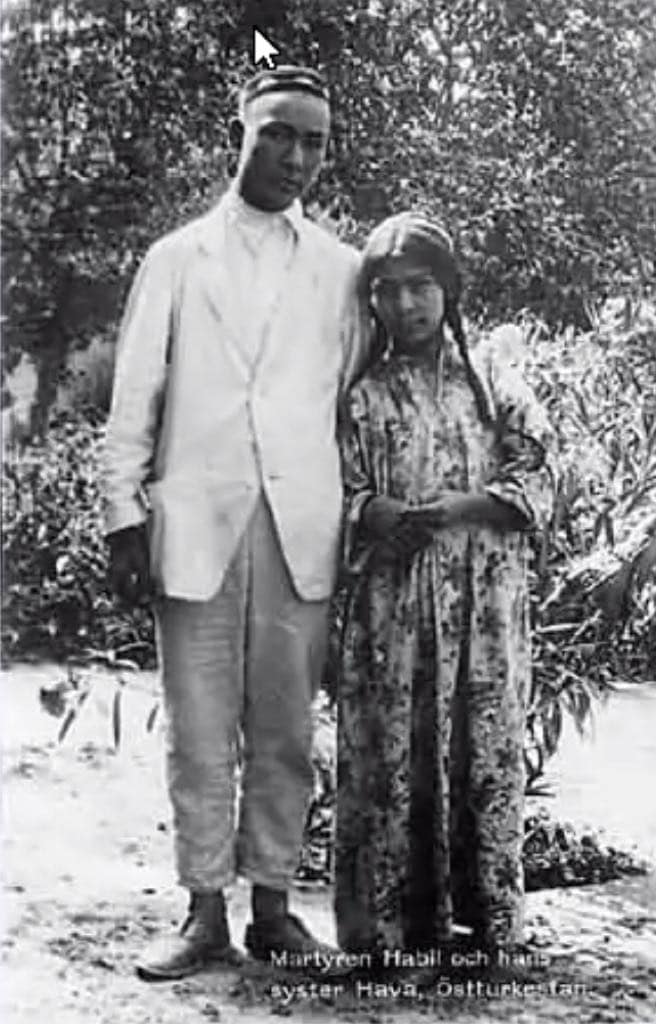

Executed during a period of turmoil and civil war in Southern Xinjiang, the eighteen year old Habil’s violent death on April 27, 1933, is being remembered by the small but growing community of Uyghur followers of Jesus around the world who have called for this day to be a memorial to his legacy.

Habil Akhond, born Mohammed, in Kashgar, Southern Xinjiang, 1914, was the son of Tohta Ahun, a carpenter cum muezzin who called the faithful to prayer five times a day in the nearby mosque. Hava, his sister, joined the family a few years later, and they grew up in a rented room of a merchant’s saray (a large wayside inn) immersed in the comings and goings of camels and horses, roguish Afghan drug smugglers and traders who plied their wares along the silk route. Uyghur traditional culture permeated their lives, with weddings and funerals, mulberries and silk worms, hours spent playing in the river on hot summer days, music, singing, dancing and of course communal prayer for men at least twice a day and the annual 30-day Ramadan fast.

Despite his firm Islamic faith, Mohammed’s father was himself trained under the Swedish missionaries and sent his children to study in their schools. He bore the brunt of being called a “kafir” (unbeliever) for this but wanted his children to benefit from the all round education provided by the Swedes, using secular textbooks printed in their own printing press, and using their own Uyghur language.

Following the arrival of a small team of Swedish missionaries in the late nineteenth century who set up clinics and schools, many in the community had already warmed to the faith of the foreigners and by the early 20th century there were more than 300 Uyghur Christians.

There were still mixed feelings towards the foreigners and their “foreign religion” and often violence would break out against them. Undeterred, it seemed as if they were there to stay and few objected to the hospitals, schools, and orphanages for destitute children they opened in the region.

But Mohammed was not sure and, although he excelled at school, kept his distance from their faith.

The Christian faith is not new for Uyghurs having been well established by 840AD during the Uyghur kingdom of Qocho (Turpan/Beshbalik) when Uyghurs also practiced Buddhism and Manichaeism. By the tenth century, the Uyghur Khanate had become a centre of Christianity with a “Church of the East” (also known as the Nestorian Church) “bishopric” in Kashgar, that thrived until the Mongol era.

Genghis Khan’s favorite wife was a Uyghur Christian; some Uyghur Christian believers held high-ranking positions in his court, undoubtedly because they knew how to read and write in the Syriac script, through which the scriptures had come to them. Increasing amounts of archaeological evidence have come to light to bear witness to Christianity’s significant presence in East Turkestan, including more than one thousand Biblical fragments recovered from the remains of a large monastery in Turpan in Syriac, Middle Persian and New Persian, and the ruins of a significant church in the ancient city of Gaochang outside the Turpan oasis.

Wide scale persecution of Christians later by Mongol rulers on embracing Islam however meant the dissipation of Christian communities, the church being driven underground and believers only remaining in isolated pockets.

Fast forward to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century when Swedish missionaries travelled over the mountains from India to set up schools and medical clinics in the south of East Turkestan, as it was known in those days, and began to win the trust and support of many of the community.

Life was turned upside down for Mohammed and Hava Han when their mother died suddenly, followed soon by their father. At twelve and six, they were orphaned with nowhere to go and no one volunteering to take them in, and the mission offered them a home together with several hundred other destitute orphans cared for by the missionaries in Kashgar and Yerken.

With its emphasis on learning through their mother tongue, Mohammed loved the Mission school’s geography and science, studying at the same time Chinese and Arabic and a range of subjects using books printed in the printing press, also carried over the mountains and assembled on arrival.

But despite increasingly feeling attracted to the Jesus of scripture he was put off by the suffering and persecution of Christians he had witnessed. A dream one night dispelled his doubts and helped him to embrace the possibility that one day he might also be called to suffer for his faith, but to see beyond the suffering to the ultimate goal; “a beautiful place full of joy and happiness” that he had seen in his dream. At his baptism he told onlookers that he had been brought to a place in his dream where he had to be willing to be crucified. This for him was the turning point. In the biography of his life, “Habil, a Christian Martyr in Xinjiang,” Swedish missionary Gustaf Ahlbert writes: “To Mohammed this was more than a dream. He felt so certain that it was Christ, who in this way, called him to eternal life and eternal blessing, but also to take up the cross and follow him. Mohammed made his choice. He was ready, with the other young boys, to join the cross-carrying group. Bravely, and with joy, he accepted Christian baptism.”

He chose a new name Abel, in Uyghur Habil, whose sacrifice had been pleasing to God in the Old Testament.

He eventually became an assistant teacher in the Kashgar mission school, fell in love with his sister’s best friend Buwe Han who had grown up in the Yerken orphanage and was dreaming of marriage, when suddenly storm clouds of political unrest and civil war loomed and the area was thrown into turmoil.

The missionaries, the Christians, and all who were associated with the Swedish mission came under fire. Cries of holy war, independence, freedom and abundance were mixed with slaughter and plunder and Emir Abdullah ruled the conquering force that was determined to rid the land of the “infidels.”

This was to include the Swedish missionaries, their orphan children and Christian believers, all of whom he ordered should be killed. Three missionaries were sentenced to death, tied up, and tied to a pole awaiting the edict but at the last minute their sentence was postponed.

Habil fled Kashgar to be with his sister and fiancée in Yerken, and as they were gathered with others singing and praying they were surrounded by soldiers who corralled them into the Emir’s palace. Soldiers were sent to the orphanage to round up the girls; they were to become spoils of war as concubines and wives to the invading force. Habil’s sister and fiancée were taken with them.

All the Christian men and boys were eventually killed in the days and months of unrest that ensued.

The Christians were bound together to be shot, but it was late and the Emir decided to take Habil as an example and a warning to the rest. He was untied, he fell on his knees, put his hands together and looked towards the sky. He didn’t plead for mercy “but just shone” say later reports.

The Emir took aim and fired; a single shot. A sword came down on his head, and his body, not allowed to be buried was thrown to the dogs. Ahlbert tells how he lay on the street for three days but no dog would come near it. “The executioners conceded that Habil was a righteous man,” he wrote.

The night before his arrest he had spent the night with his friend Jacob Stephen. They had prayed together. Not knowing what lay ahead for him the next day, Habil had made a drawing of a cross and then a crown. He had told Jacob, “First the cross and then the crown.”

Margareta Höök, daughter of two of the Swedish missionaries serving in East Turkestan at that time, speaking to Bitter Winter, told of her mother’s diary entry from that day. She had been in Sweden at the time but retells her husband Ivar Höök’s account of the events of that night. “At the same time as our three missionary coworkers were arrested, the Emir arrested our Christians in Yarkand and all the children in the children’s homes. Oh what weeping and wailing! But this was not enough! He also had Habil Akhond, our young faithful Christian, killed. The blood of the martyrs is the seed of Christianity.”

Tashten, a modern day exiled Uyghur Christian believer, speaking to Bitter Winter about the Habil’s martyrdom described it as a “sad day” but one that inspires in him courage and hope. He felt that Habil’s steadfastness in the face of terror and violence had been a witness to him of the reality of the words of Jesus in the New Testament’s Matthew 5:11,12: “Blessed are you when people insult you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

He wrote a poem for Habil’s memorial day describing his own faith as a Christian Uyghur.

“On the road”—by Tashten

I’m on this road

Even though I’m in the shadow of death.

Whatever might befall me, I will not fear,

Because you Lord are with me.

Dear friend, even painful days

Won’t stop me carrying on.

Dear friend, even though I might walk through the desert,

I won’t be deterred.

Because I’m dancing in a heavenly Meshrep

With my Lord.

I’m dancing the Sama [traditional Uyghur dance]

With my Lord.

I’m riding the buffeting waves,

Forging through the winter’s storms,

Until I reach my heavenly resting place.

يولدا

ماڭىمەن بۇ يولدا ،

گەرچە ۆلۇملەر يېقىن

قورۇقمايمەن ھىچبىر زامان،

رەببىم سەن ماڭا يېقىن.

دوستۇم مۇشكۇل كۈنلەرمۇ

توساپ قالالماس مېنى.

دوستۇم چۆل-دەستە باياۋان

تۇتۇپ قالالماس مېنى.

ويناپ مەن رەببىم بىلەن

ۇسۇل مەشرەپتە

ويناپ مەن رەببىم بىلەن

ۇسۇل سامادا.

دولقۇن يېرىپ، شىۆىرغان كېژىپ

ارام گاھىمۆا يەتكۈچە .

(تاشتېن)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.