St Thomas Aquinas, the Angelic Doctor, called Aristotle 'THE Philosopher'. Here is his view of usury, which Thomas proved is a sin.

[1258b] [1] (for it is not in accordance with nature, but involvesThe musings and meandering thoughts of a crotchety old man as he observes life in the world and in a small, rural town in South East Nebraska. I hope to help people get to Heaven by sharing prayers, meditations, the lives of the Saints, and news of Church happenings. My Pledge: Nulla dies sine linea ~ Not a day without a line.

31 March 2022

Aristotle on Usury

Which Catholic Saint Changed the US Tax Code?

As tax day, 15 April, approaches, may St Katharine Drexel pray for us all! This is, however, a fascinating story.

By Matthew Archbold

I found this fascinating. If your taxes are lessened through charitable giving, you may want to thank a saint.The Arkansas Catholic reports:

St. Katharine Drexel is well known for being a trailblazing figure in the early 20th century, championing the needs of Native Americans and Black Americans, but few know she may have the most lasting impact on philanthropy of any American in U.S. history.

Her unexpected role in the U.S. tax code began at the outbreak of World War I in 1913, which spurred the creation of the federal income tax.

But by 1917, the tax became a graduated one, sending Mother Katharine’s tax bills skyrocketing and potentially endangering the charitable work of her religious order, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. The sisters’ motherhouse is in Bensalem, Pa.

“What made her unique is the order of magnitude. There were years where the amount she gave was almost equal to the combined amount of all the collections and all the parishes in the entire country.”

By 1924, Mother Katharine and her influential family successfully lobbied Congress for what later became known as the “Philadelphia nun provision.” Under the provision, anyone who had given 90% of their income to the charity for the previous 10 years was exempt from income taxes.

It was a distinction that described only one U.S. citizen at the time — Mother Katharine, said Seth Smith, clinical assistant professor of history at The Catholic University of America in Washington.

Phil Brach, vice president of college relations at Belmont Abbey College in North Carolina, said the “Philadelphia nun provision” goes to the heart of what set Mother Katharine apart from her better-known philanthropic contemporaries such as John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie.

“What made her unique is the order of magnitude,” said Brach, who has taught courses on philanthropy for Catholic University in Washington. “There were years where the amount she gave was almost equal to the combined amount of all the collections and all the parishes in the entire country.”

Mother Drexel’s giving mostly benefited Black Catholics and Native American Catholics at a time when racial prejudice ran high and those communities struggled with crippling poverty and lack of access to quality education. Her order built schools and churches across the American South and established what is now Xavier University of Louisiana, the nation’s only historically Black Catholic college.

Mother Drexel also was a staunch supporter of the Josephites throughout her life, purchasing land for the religious order to build many of their parishes and schools.

St. Katharine’s family, the Drexels of Philadelphia, was one of the wealthiest families in America. An heiress to a banking fortune who chose religious life, she devoted her wealth to Blacks and Native Americans served by her religious order and to other people in need. She gave approximately $20 million dollars over her lifetime…

“There is a reason she’s the patron saint of philanthropy,” Brach told The Josephite Harvest, the magazine of the Josephites, known formally as St. Joseph’s Society of the Sacred Heart.

According to “Sharing the Bread in Service: Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament 1891-1991 — Volume 1,” the “Philadelphia nun provision” was essential to the operation of the order in the years after it became part of the law.

“The exemption was really important because the sisters were responsible for basically taking care of 15,000 dependents annually. They had over 300 employees or teachers,” Smith said. “They also contributed annually over $50,000 to support Black and Native American children in schools outside of their own.”

“Frankly, the church historically has fallen short, with Black Americans to the South, but the greatest legacy of Catholic support is in those schools,” Smith said.

According to “Sharing the Bread,” allies of Mother Katharine urged her to seek a refund for almost $800,000 — the equivalent of about $13 million in today’s money — that she had paid the government before the provision took effect, but Mother Katharine declined, worried that it would exacerbate anti-Catholic prejudices at the time…

The “Philadelphia nun provision” was eventually written out of the tax code in 1969, but Mother Katharine’s influence on U.S. philanthropy can’t be understated, Branch said.

“The official language may be out of the code, but in general, it is the genesis of the charitable deduction that still exists,” he said.

That’s a pretty good legacy, huh? I mean, it’s not as good as becoming a saint and showing people the way to Heaven but it’s pretty awesome.

Is There a Global Vocations Crisis? A Look at the Numbers

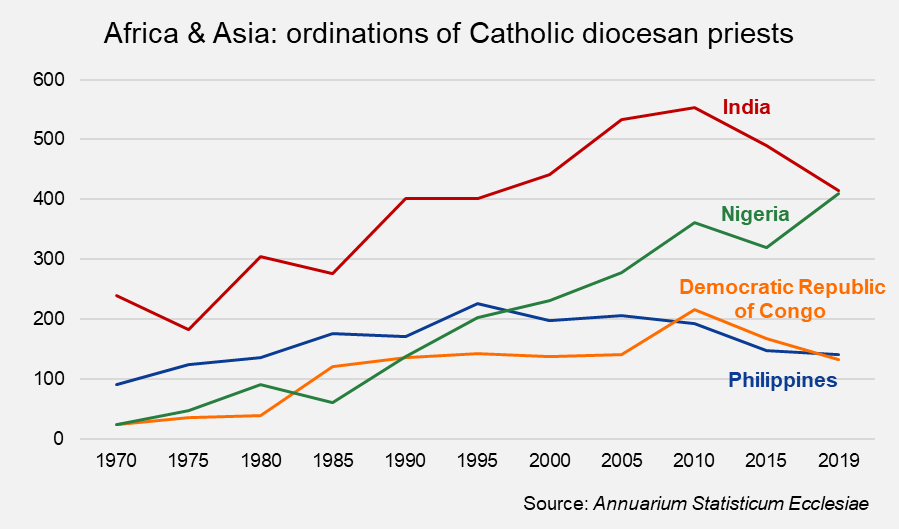

In 2019, India, Catholic population just over 20 million and the U.S, Catholic population 70.5 million, both ordained 415 men to the diocesan priesthood.

From The Pillar

By Brendan Hodge

While ordinations to the diocesan priesthood are on the rise in some parts of the world, they’re also falling fast in some traditionally Catholic countries.

And while a “vocations crisis” might be discussed most often in the United States, where more than one-third of diocesan priests are currently in retirement, the global picture of diocesan priestly ordinations points to changing trends and dynamics in the Catholic Church.

The number of priests around the world is holding steady, but the Catholic population is growing — which suggests a need for more priests, even in some of the most vibrant parts of the world.

The Pillar looks at the numbers.

The big picture

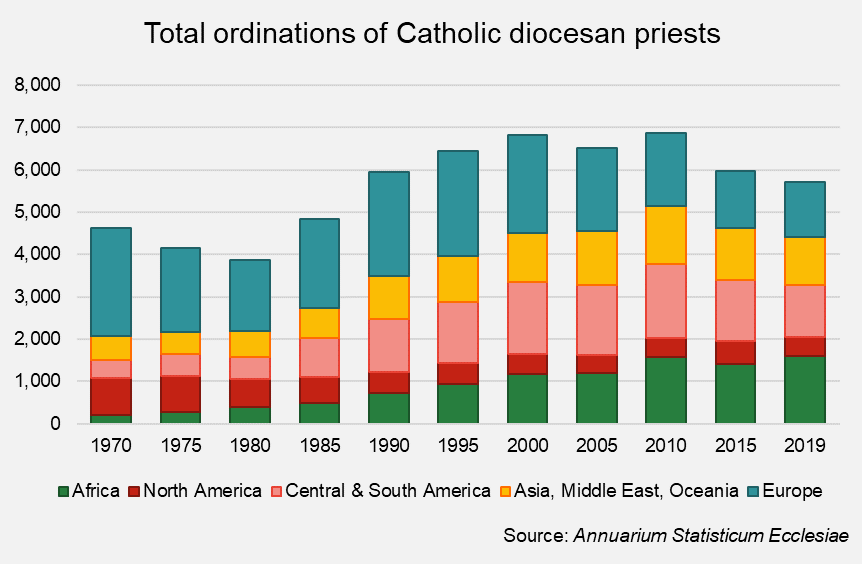

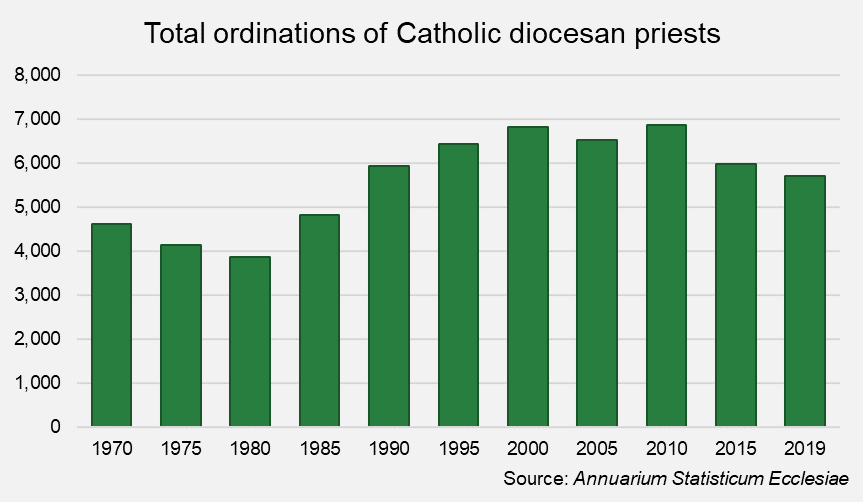

Since 1970, the Vatican has compiled an annual handbook of Church statistics which tracks ordinations to the diocesan priesthood.

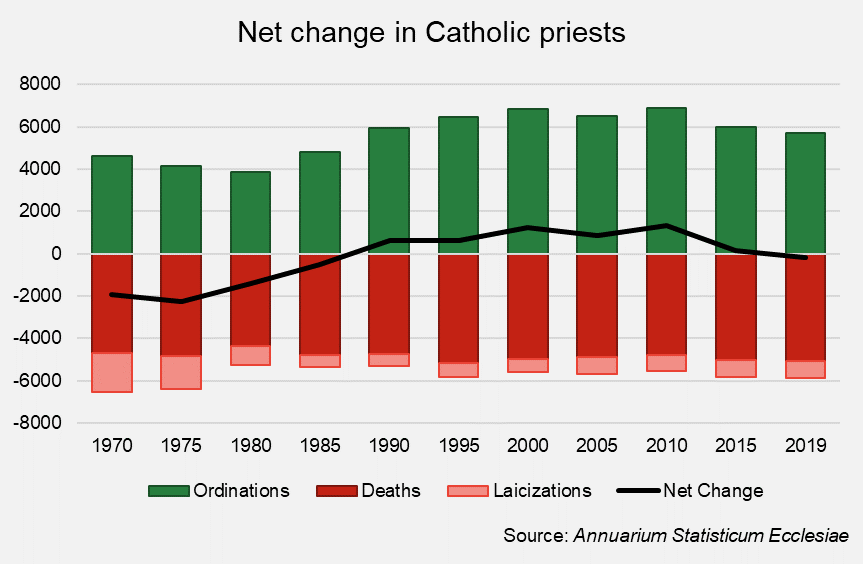

The highest number of ordinations to the diocesan priesthood in the global Church since 1970 came in the decade between 2000 and 2010, when the Church ordained around 6,800 men annually as diocesan priests.

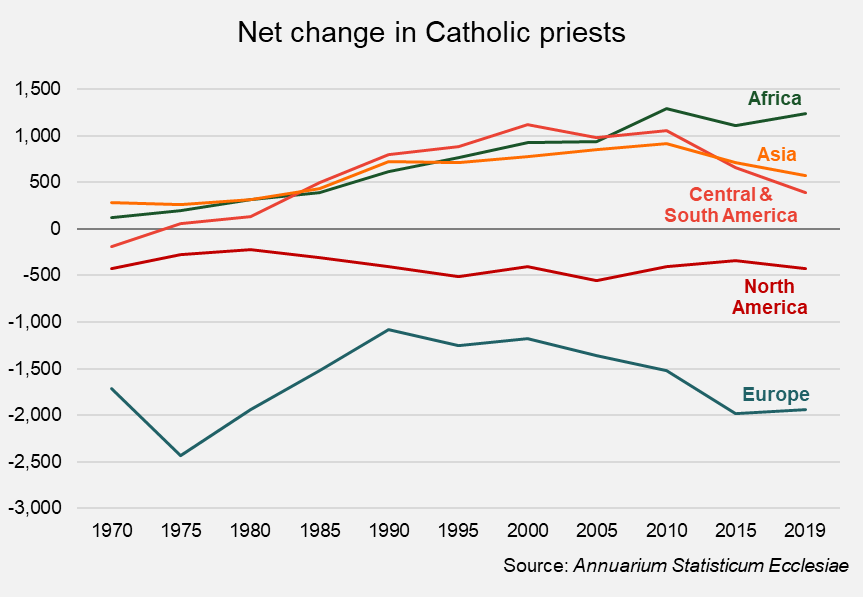

In 1970, Europe accounted for 55% of all the Church’s ordinations to the diocesan priesthood. By 2019, the absolute number of men ordained in Europe had dropped by nearly 50%, and Europeans made up only 23% of all ordinations — European diocesan priesthood ordinations were outnumbered by Africans, who made up 28%.

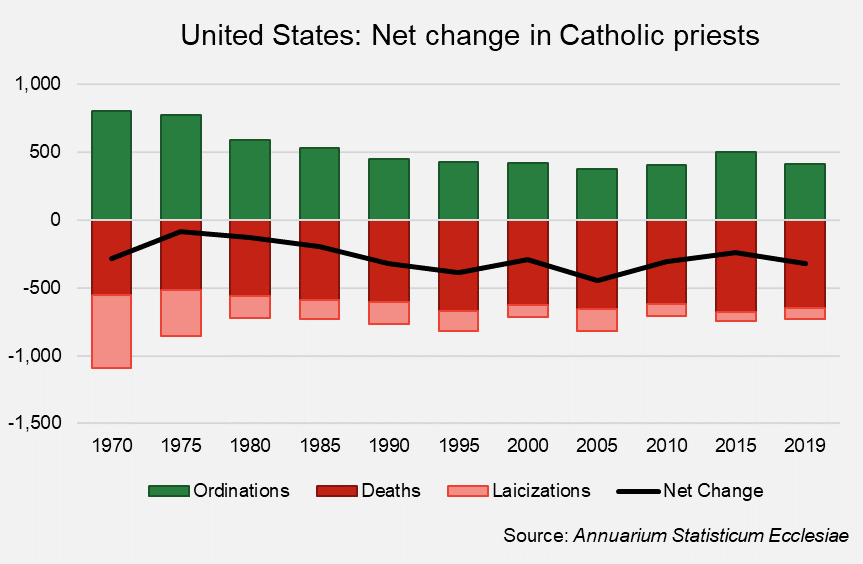

The number of diocesan priests ordained in North America dropped 50% between 1970 and 2000, but has since leveled off.

In Central and South America, as well as in Asia, the number of diocesan priestly ordinations increased dramatically from 1970 to 2010, but has since begun to drop.

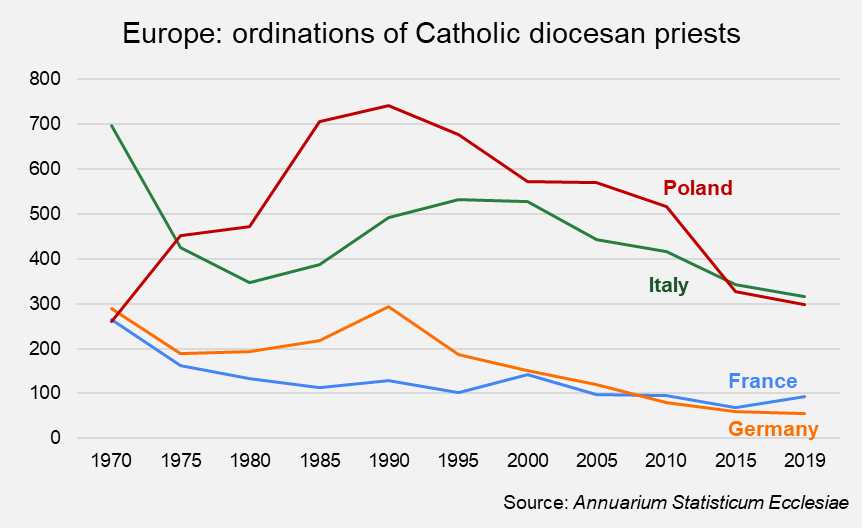

The Church in Europe

Within Europe in particular, there is a great deal of variation between countries.

Italy saw a 50% decline in diocesan priestly ordinations from 1970 to 1980, some increases in the 1990s, and then a new period of decline.

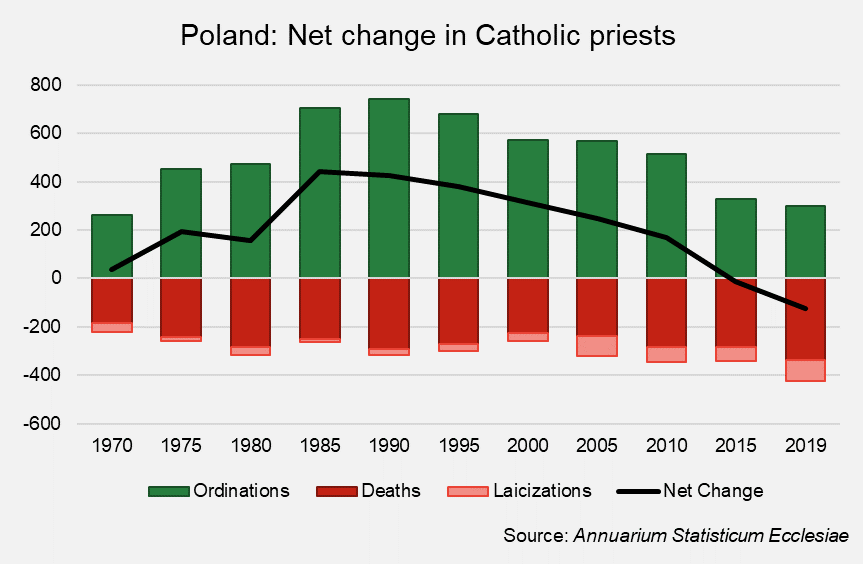

Poland saw a rapid increase in diocesan ordinations during the 1970s and 1980s, peaking around 1990, as the country freed itself from communism.

But the number of diocesan priestly ordinations in Poland has fallen over the last 30 years. In 2019 there were 298 men ordained priests, less than half the 741 who were ordained in 1990.

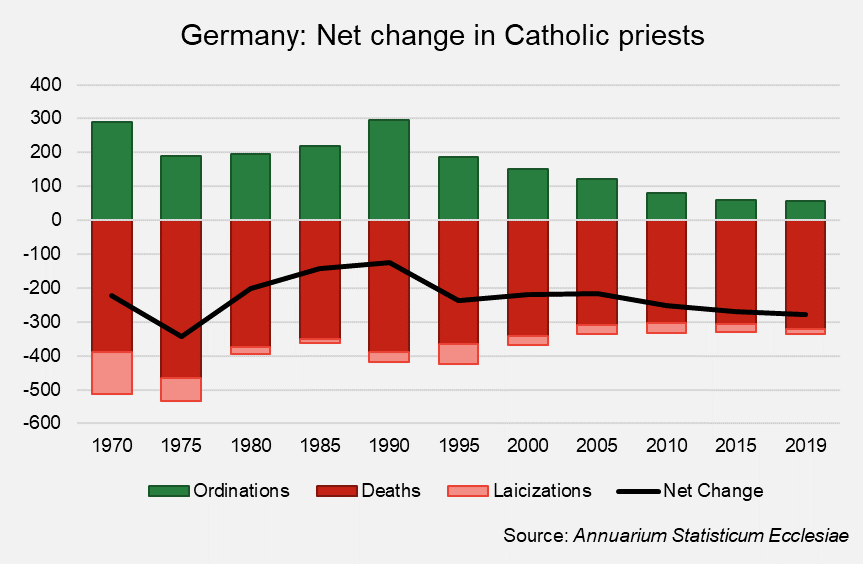

In 1970, France and Germany each had nearly 300 men ordained to be diocesan priests.

Since that time, ordinations in both countries have declined, though Germany saw an increase in ordinations during the waning years of communist rule, peaking in 1989 and 1990 as the Berlin Wall fell and Germany was reunited.

In 2019, France ordained 94 new diocesan priests, while Germany ordained 55.

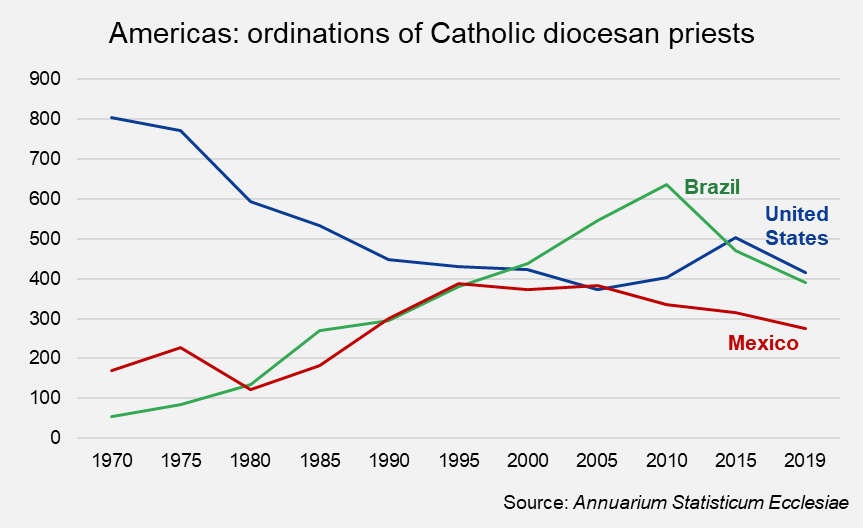

The Americas

The United States has experienced a different ordinations trend from what the Catholic Church has seen in Central and South American countries.

U.S. diocesan priestly ordinations decreased by nearly 50% from 1970 to 1990, but have averaged 428 per year since that time, despite some variation from year to year.

In Mexico, the number of diocesan priestly ordinations peaked between 1995 to 2005. While the number of diocesan priests ordained each year has declined since that peak, it is still well above the level of 1970.

Brazil’s number of annual diocesan priestly ordinations increased steadily from 1970 to 2010, but has since declined, and is now at level last seen in 1995.

Although both Mexico and Brazil have seen more diocesan priests ordained in recent years than they did in the 1970s, the number of Catholics in those countries has grown at even faster rate, presenting a looming crisis to provide ministry to all those nations' Catholics.

In 2019, Brazil had over 11,000 Catholics for each diocesan priest and Mexico had over 8,000.

By comparison, the United States has under 3,000 Catholics per diocesan priest. That number will grow in the coming years, as U.S. priestly ordinations will decline for several decades before stabilizing, based on the current rate of vocations.

Asia and Africa

Asia and Africa have seen some of the most dramatic increases in priestly vocations since the 1970s.

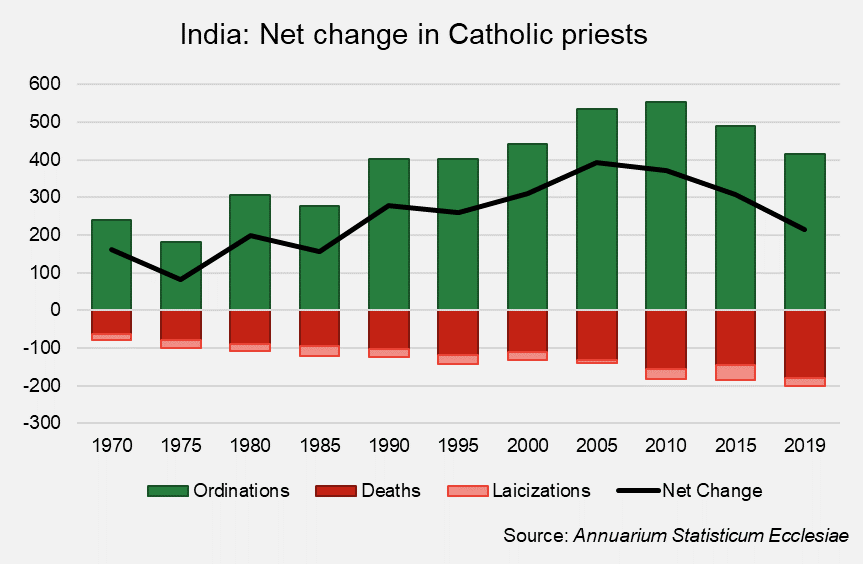

With 1.38 billion residents, India has the second largest population in the world, and will likely pass China within the next few years.

But India’s Catholic population of 22.5 million - which is spread between the Latin Catholic Church and two other sui iuis Catholic Churches - is smaller than that of the number of Catholics in the United States or even Germany.

India has produced a rapidly growing number of priestly vocations for most of the last 50 years, peaking in 2010 with 553 men ordained Latin Catholic diocesan priests – more ordinations that year than the United States, which has three times the number of baptized Catholics.

In 2019, India and the U.S. both ordained 415 men to the diocesan priesthood.

The Philippines has a smaller population but is a majority Catholic country. Its trend in ordinations is similar to that of Mexico, increasing from 1970 to 1995 but declining since that peak.

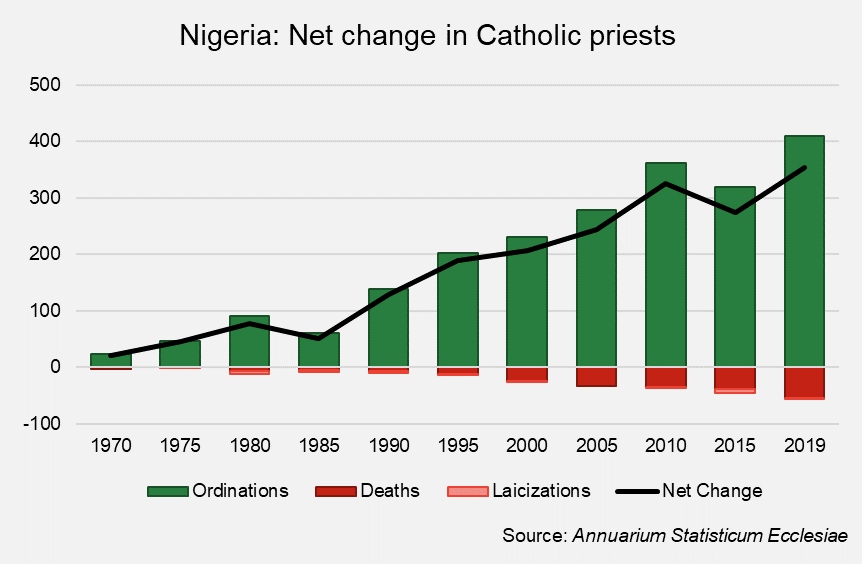

Nigeria is the lodestar of Africa’s vocations boom. With 31.5 million Catholics in 2019 (less than half the number in the United States) Nigeria has increased steadily in vocations since 1970, and in 2019 saw only five fewer men ordained priests than the United States, despite the differences in Catholic population.

The Democratic Republic of Congo has a population which is just over 50% Catholic, giving it more total Catholics than Nigeria. But the country’s number of priestly vocations is smaller.

From 1970 to 2010 the number of priestly ordinations increased in the DRC by more than eight times, to 216.

But the 2019 number was somewhat lower, at 133.

Casting nets

Of course, this analysis focuses on diocesan priests, who consistently form the majority of priests ministering in parishes around the world.

But to examine the impact of vocations on the total number of diocesan Catholic priests, it is necessary to view the number of ordinations against the number of priests who die or are laicized.

In the 1970s and 1980s the net change in priests was negative, because of large numbers of priests seeking laicization in the 1970s, and a dramatic decrease in the number of ordinations in Europe and North America in the years following Vatican II.

In the 1990 and 2000s, the net change in the number of priests turned positive, as the number of laicizations declined and the number of ordinations in Africa and Asia increased.

But in the last few years the net change in the number of priests has sputtered at neutral, because of a slowdown in diocesan priestly ordinations in the developing world, and the death of priests ordained in the 1960s and early 1970s.

But while the number of diocesan priests globally remains flat, the number of Catholics around the world is continuing to increase.

Europe and North America are seeing a net decrease in the number of diocesan priests each year, while countries in many parts of the developing world see a positive net change each year.

Europe’s numbers are driven by countries with traditionally large Catholic populations, which have suffered increasing secularization.

Germany is a key example of that trend: 321 German priests died in 2019 and 14 were laicized, while only 55 were ordained. For every six diocesan priests lost, only one new diocesan priest was ordained.

Italy and Poland have had comparatively high numbers of diocesan priestly vocations even after Vatican II. But both countries have seen a negative change in the number of diocesan priests in recent years; the number of priestly ordinations has slowed and the postwar generation of priests has begun to die.

The United States has seen negative net changes in the number of diocesan priests every year since 1970. But a steady number of ordinations over the last 30 years suggests that the number of diocesan priests in the U.S. might stabilize in the years to come, if current trends continue.

In countries like as Brazil and India - where the number of diocesan priestly ordinations in recent years has been much higher than the number 50 years ago - the net change in the number of priests remains positive, but the number of ordinations has declined somewhat in recent years.

And in countries like Nigeria where the number of diocesan priestly ordinations per year is steadily increasing, the annual net change in diocesan priests continues to march upwards.

The numbers and graphs are interesting in their own right.

But for diocesan bishops around the world, they can serve as a barometer of the health of their dioceses — diocesan priestly vocations often points to a healthy ecclesial culture in both families and parishes. Of course, there are exceptions to that generalization.

But as bishops, and ordinary Catholics, think about the future of the Church, the trends in diocesan priestly ordinations are an important piece of the puzzle.

Popes, Liturgy, and Authority (3): S Pius V Compared with S Paul VI and PF

Fr Hunwicke has some further thoughts on his posts that I shared here on Popes, Liturgy, and Authority, clearing up a common misconception.

From Fr Hunwicke's Mutual Enrichment

We are sometimes told that the imposition of a new rite by S Paul VI is precisely what S Pius V did in 1570.

It is not.

What S Paul VI did is precisely the opposite of what S Pius V did..

People who tell you anything different either have not read Quo primum ... or cannot understand Latin ... or have a regrettably fugitive grasp upon Truth.

S Pius V dealt with the question of churches with a Use of more than 200 years (i.e., going back to before the invention of printing made life so easy for liturgical tinkerers and innovators) in the following way.

He said "nequaquam auferimus" -- in no way whatsoever do we take it (their old rite) off them.

It is true that he added a "permittimus" -- we permit that, if they like my edition of the Missal better, they can adopt it "de episcopi vel praelati capitulique universi consensu" -- provided that the bishop and the unanimous Chapter are in agreement.

If S Paul VI ... or PF ... had really wished to behave like S Pius V, they would have needed to decree something like this:

"We do not take away the right to use a Missal with more than 200 (or 600? Or 1200?) years of lawful use; but if a Bishop and his entire Chapter really do want to use my Novus Ordo instead, I will permit them to do so."

Jesuit Martyrs and the Tudor Terror

Can you imagine any Jesuit today dying for the Faith? James (Jimmy Boy) Martin, SJ? Antonio (2+2=5) Spadaro, SJ? I certainly can't!

By Joseph Pearce

Editor’s note: The following in an exclusive excerpt from Joseph Pearce’s new book, Faith of Our Fathers: A History of True England (Ignatius Press).

In October 1588, a few short weeks after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, a young Jesuit priest, just turned twenty-four-years-old, landed secretly on the coast of Norfolk. This was Father John Gerard, who was destined to become one of the most successful of all the missionary priests and therefore one of the most wanted by Elizabeth’s government. He would serve the English mission in East Anglia for the next five and a half years, evading arrest and eluding the authorities. He was finally arrested in April 1594 and then, after three years in prison, was moved to the Tower of London to be tortured. In October 1597 he made a daring escape from the Tower, by means of a rope stretched from a cannon on the roof of one of the towers across the moat to a wharf on the river Thames.

Father Gerard remained at large for the next eight years, moving mostly between Northamptonshire and London, serving England’s Catholics, including those high-ranking Catholics who had access to the queen’s court, such as the Earl of Southampton, a favourite of the queen who was, at the same time, a devout Catholic and confidant of the Jesuit priest, St. Robert Southwell, as well as being William Shakespeare’s patron. William Byrd, composer of the Chapel Royal, was another of the queen’s favourites. Although Elizabeth knew of Byrd’s recusancy, she not only chose to turn a blind eye to it but instructed her ministers to protect him from the anti-Catholic laws. On more than one occasion, court records show that efforts to fine Byrd and his wife for their refusal to attend Anglican services were abandoned “by order of the Queen’s Attorney General”.1 Not only did Elizabeth intervene personally to rescue Byrd from persecution, she even made him a gift, in 1595, of the lease of Stondon Place, in recognition of his faithful service as her court composer. And yet, according to Byrd’s biographer, “loyal and circumspect as Byrd undoubtedly was, he was more intimately involved in Catholic circles, and probably knew more about Catholic intrigues, than is betrayed by the bare written records”.2 If this is true of Byrd, it is equally true of William Shakespeare, who was raised in a recusant home and who appears to have retained his Catholic sympathies following his arrival in London.

The parallels between William Byrd and William Shakespeare are worthy of note. There is evidence that Byrd might have known the Jesuit martyr, Edmund Campion, as there is evidence that Shakespeare probably knew the Jesuit martyr, Robert Southwell, and it is conjectured that Byrd might have been in the crowd who witnessed Campion’s martyrdom, and that Shakespeare might have witnessed the martyrdom of Southwell. William Byrd set part of St. Henry Walpole’s poem eulogizing Campion to music, risking the ire of the queen by publishing his musical setting of the poem in 1588, and Shakespeare alludes to the poetry of St. Robert Southwell in several of his plays, including Romeo and Juliet, The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet and King Lear.

If Jesuit priests, such as John Gerard and Robert Southwell, managed to evade capture for several years, other newly-arrived priests were not so fortunate. Four priests who arrived on the north-east coast of England in March 1590, expecting to be met as they landed and then taken from one safe house to another, found that they were utterly alone and without any help, the underground network having been betrayed by spies. With little option but to make the long journey south without any assistance, they made the fatal mistake of travelling together and not splitting up. Betrayed by someone who pretended to be a Catholic to gain their confidence, they were tried and executed. Fathers Richard Hill, John Hogg, Richard Holiday and Edmund Duke were hanged, drawn and quartered on May 27, 1590, at Dryburn on the outskirts of Durham.

The way in which the homes of recusants were raided and searched by the government’s priest-hunters was described by Robert Southwell:

Their manner of searching is to come with a troop of men to the house as though they come to fight a-field. They beset the house on every side, then they rush in and ransack every corner – even women’s beds and bosoms – with such insolent behavior that their villainies in this kind are half a martyrdom. The men they command to stand and to keep their places; and whatsoever of price cometh in their way, many times they pocket it up, as jewels, plate, money and such like ware, under pretense of papistry…. When they find any books, church stuff, chalices, or other like things, they take them away, not for any religion that they care for but to make a commodity.3

In October 1591, nine or ten Jesuits, several other priests, as well as a number of laymen who were living in hiding, were gathered for a conference at Baddesley Clinton, a large recusant house in Warwickshire. Fearing that there were not enough priest holes in which to hide such a large number of outlaws, the meeting was kept short. Several of the priests and laymen dispersed, leaving the remnant at the house. At five o’clock on the following morning, the house was raided. “I was making my meditation,” wrote Fr. Gerard, “Father Southwell was beginning Mass and the rest were at prayer, when suddenly I heard a great uproar outside the main door.” There was much shouting and swearing at a servant who was refusing entrance to the priest-hunters. Had not this “faithful servant held them back … we should have all been caught.”

With no time to lose, Fr. Southwell slipped off his vestments and stripped the altar bare. Meanwhile, the other priests grabbed all their personal belongings so that nothing was left to betray the presence of a priest. “Even our boots and swords were hidden away,” wrote Fr. Gerard, “they would have roused suspicions if none of the people they belonged to were to be found.”4 The five Jesuit priests, three of whom were destined to die martyrs’ deaths, two secular priests and two or three laymen clambered into a sort of cave hidden underground, the floor of which was covered with water. Here they remained for four hours while the priest hunters delved into every corner, and every nook and cranny, seeking in vain for their prey. Although Robert Southwell escaped the clutches of Elizabeth’s henchmen on this occasion, he would finally be betrayed the following year after eluding capture for six years. He would face three years of brutal torture, never once divulging information to his torturers. His astonishing resilience and courage earned him the grudging respect of one of those who witnessed his excruciating suffering. “They boast about the heroes of antiquity,” wrote Robert Cecil, the son of Lord Burghley (William Cecil), Elizabeth’s chief minister, “but we have a new torture which it is not possible for a man to bear. And yet I have seen Robert Southwell hanging by it, still as a tree trunk, and no one able to drag one word from his mouth.”5

In the autumn of 1593, another Jesuit, Fr. Henry Walpole, set sail for England. His journey was tracked by Elizabeth’s spies and he was hunted down and arrested only three days after he had landed at Bridlington in Yorkshire. After a brief period of imprisonment in York Castle, he was transferred to the Tower of London. There he was tortured on no fewer than fourteen occasions under the supervision of the sadistic Richard Topcliffe, suffering the same grisly fate as his Jesuit confrere, Robert Southwell. Both men would be hanged, drawn and quartered, the common fate of most of the martyrs, in 1595.

Standing in the cart at Tyburn, beneath the gibbet and with the noose around his neck, Fr. Southwell made the sign of the cross and recited a passage from Romans, chapter nine. When the sheriff tried to interrupt him, those in the crowd, many of whom were sympathetic to the Jesuit’s plight, shouted that he should be allowed to speak. He confessed that he was a Jesuit priest and prayed for the salvation of the queen and his country. As the cart was drawn away, he commended his soul to God in the same words that Christ had used from the Cross: In manus tuas (Into your hands Lord I commend my spirit). As he hung in the noose, some onlookers pushed forward and tugged at his legs to hasten his death before he could be cut down and disemboweled alive. Southwell was thirty-three-years-old, the same age as Christ at the time of his Crucifixion.

Endnotes:

1 David Mateer, “William Byrd’s Middlesex Recusancy”, Music and letters 78, no. 1 (February 1997), 1-14

2 John Harley, William Byrd: Gentleman of the Royal Chapel (Bookfield, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing, 1997), 77

3 Robert S. Miola, ed., Early Modern Catholicism: An Anthology of Primary Sources (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 34

4 John Gerard, The Autobiography of an Elizabethan (Oxford: Family Publications, 2006), 41-2

5 Hugh Ross Williamson, The Day Shakespeare Died (London: Michael Joseph, 1962), 57

Faith and Evidence

Lesson Twenty of Aquinas 101, with Fr. James Brent, OP, PhD, STL, Asst Professor of Philosophy, Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception, Washington DC.

Is there sufficient evidence to believe in the mysteries of the Christian faith? What we believe is no lie, legend, or lunacy.

Famous Nuns of 'Dialogue of the Carmelites' Might Soon Be Named Saints

From Aleteia

By I. Media

The 16 Carmelite nuns of Compiègne could soon be canonized, with the so-called equivalent, or “equipollent” procedure, which recognizes devotion that is already established and perennial.

The nuns were guillotined on July 17, 1794, during the French Revolution and are known throughout the world thanks to the famous “Dialogues” that Bernanos dedicated to them, which in turn was based on Gertrud von Le Fort’s novel Die Letzte am Schafott (1931; The Song at the Scaffold), and was made into an opera.

I.MEDIA spoke with the coordinator of the file in France and with the postulator of the cause in Rome, as Pope Francis had given permission to submit the file to the Congregation for Saints’ Causes on January 20, 2022.

Back in the 1990s, John Paul II was astonished before Bishop Guy Thomazeau, then Bishop of Beauvais — the diocese on which Compiègne depends — that the famous nuns had not yet been declared saints. The file has been bogged down several times, but was recently reopened when the bishop emeritus entrusted the task to Claire Millet, a secular laywoman in the Carmelite Order.

Months of efforts were finally ratified by the unanimous vote of the bishops of France at their fall assembly (November 2021). The present Carmelites of Jonquières-Compiègne, supported by all the branches of the Carmelite Order, then submitted their official request in December, obtaining a favorable response from the Pontiff a month later.

Why the “equipollent” procedure?

With the “equipollent” canonization, the inscription of the saints is done by a simple decree of the pope without the regular process, which involves verification of a miracle. Marco Chiesa, the postulator, explains that “they must have enjoyed a long and uninterrupted devotion, as well as a reputation for signs and graces.” Their canonization is requested by a large representation of the Church, directly to the pope.

Pope Francis has recognized a number of saints with equivalent canonization, including Peter Faber, Marie of the Incarnation, and Angela of Foligno.

Benedict XVI used the same recognition for St. Hildegard of Bingen, who is also recognized as a doctor of the Church.

Benedict XIV formalized this process in the 1700s. Through it, a pope invites the universal Church (as opposed to the local place where a saint might have been from, or a particular religious order he or she belonged to) to recognize the feast of the saint, with Mass and the Divine Office.

This recognizes that the Church’s judgment has been made on the person’s sanctity, even though the usual formula of canonization hasn’t been made.

This process is “an absolute novelty for our Order,” confides the Carmelite, who is in charge of drafting the “positio.”

“We work directly with the Dicastery for Saints’ Causes,” he explains, “seeking to document the uninterrupted devotion dedicated to the Blessed and their beneficial influence on the lives of the faithful, which is expressed in signs and graces.”

The procedure could now be quite fast, says Millet, who expresses the wish of Christians of France that the canonization could be celebrated at the reopening of Notre Dame de Paris in 2024. However, “the process is in its early stages,” the postulator cautiously moderates, “and it is difficult to know how long it will take.”

For the time being, a team working with the nuns of Jonquières-Compiègne is in charge of collecting and cataloguing the testimonies that are pouring in. “There is an incredible number of signs of piety, letters and emails from all over the world,” says Millet. “We just opened a Twitter address, and within 15 minutes of its opening there were 400 tweets requesting prayers and reactions! The same goes for Facebook. In Jonquières, in the current convent of the Carmelites, there is a whole floor of archives, which contains 15,000 signatures of petitions to ask for the canonization.”

A story of sacrifice for peace

“Their cause is known to the whole world, most probably through the script of Bernanos published in 1949,” Claire Millet emphasizes. Even if the writer took some liberties with the story, adding fictional characters, his Dialogues of the Carmelites was followed by an opera by Poulenc, films, and countless publications contributing to the worldwide fame of these nuns.

According to the Carmelite archives, the community’s sacrifice is to be understood in the light of a premonitory dream: “At the end of the 17th century,” says Millet, “a Carmelite nun from this convent saw her sisters ascending to Heaven carrying the Palm of the Martyrs. This has remained in the spiritual heritage of this Carmelite convent. In September 1792, in the midst of the Terror, the prioress interpreted this dream as a sign, proposing to the Carmelites to offer their lives, to make a consecration so that peace might be restored to the Church and to the State.”

After threats and denunciations in a climate of persecution by the Church, the nuns were taken from Compiègne to Paris by cart. They were brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal on July 17, 1794. Condemned, they were executed the same evening at 8:00 p.m. in the Place du Trône — today’s Place de la Nation — and their bodies were thrown into the Fosse commune de Picpus.

Their crime? “Fanaticism and sedition,” declared the public prosecutor. Their story made a lot of noise and became anchored in popular memory. Especially since, when they went up to the scaffold one by one, each of the nuns kissed a little statue of the Virgin held in her hand by their prioress. Before being guillotined in turn, the prioress gave the statue to the crowd, and it became a relic preserved and prayed before today in the crypt of the Carmel of Jonquières-Compiègne.

In the eyes of the Church, it is clear that the 16 Carmelites died “for their attachment to the holy religion. They did not want to renounce their faith,” emphasizes Millet. Recognized as martyrs, they were beatified on May 27, 1906, by Pope Pius X and their feast day was included in the liturgical calendar on July 17.

A heritage that bears scars

“They offered their lives, which gives meaning to their death,” insists Millet. This is the key message that makes this cause incredibly relevant today. They sacrificed themselves for Peace, which we all need so much today.

However, the issue remains delicate in the face of recuperations that would awaken the old scars of the French Revolution. The 16 nuns of Compiègne, says Fr. Chiesa, became martyrs “in the name of those principles that they were already living, but of which they were absurdly deprived: liberty, equality and fraternity.”

For the postulator, this reveals that “every ideology, whatever its form and origin, carries with it a trail of blood, as we still see today in the world, even if it does not make the headlines.”

Chiesa concludes, “Canonizing these 18th-century martyrs today is to encourage the hour of the saints, as Georges Bernanos spoke of: ‘It is sanctity, it is the saints who maintain that interior life without which humanity will degenerate until it perishes. […]. Without a doubt, one could believe that it is no longer the hour of the saints, that the hour of the saints has passed. But as I once wrote, the hour of the saints always comes.'”