Musings of an Old Curmudgeon

The musings and meandering thoughts of a crotchety old man as he observes life in the world and in a small, rural town in South East Nebraska. I hope to help people get to Heaven by sharing prayers, meditations, the lives of the Saints, and news of Church happenings. My Pledge: Nulla dies sine linea ~ Not a day without a line.

23 January 2026

Pope Leo Appoints A Stunning And Brave James Martin Disciple To Lead Priests

Pretty much every single appointment of Pope Leo's has been disastrous, but it's not enough to cause some observers to accept the truth.

The Monk Who Saved The Middle Ages From Crisis

Traditional Catholic Morning Prayers in English | January

Traditional Catholic Christmas morning prayers to help start your day. Christmastide begins with Christmas and extends to Candlemas on February 2. Prayers for the Christmas season, in honour of the Nativity and the Virgin's birth of Christ, the Saviour of the world. This morning prayer video is a compilation of many traditional morning prayers Catholics say, and should not be considered a replacement for those who have an obligation to pray the Divine Office morning prayers.

The 400 BC Prophecy That Makes Protestant Communion Impossible

St Raymond's Advice on What To Do When You Are Persecuted

St Raymond, whose Feast is today, may have invented windsurfing when the King forbade him from boarding a ship and he sailed from Majorca aboard his cloak!

From Aleteia

By Philip Kosloski

If you are feeling persecuted by family, friends, or the government, fix your eyes on Jesus Christ.

Christians in every age are persecuted, whether it involves a coordinated effort by those in power, or (sometimes even more painful) an attack from family and friends.

Whatever type of persecution we may be experiencing, it typically isn't easy to endure.

St. Raymond of Penyafort had some wise words to say about persecution, featured in the Church's Office of Readings.

Set your eyes on Jesus Christ

He explains first how anyone who lives by the Gospel will be persecuted, "The preacher of God’s truth has told us that all who want to live righteously in Christ will suffer persecution."

If Jesus Christ was persecuted, how can we escape it?

St. Raymond recognizes that persecution is especially difficult to endure when it comes from within, whether that is from the Church, or from family and friends:

The sword falls with double and treble force externally when, without cause being given, there breaks out from within the Church persecution in spiritual matters, where wounds are more serious, especially when inflicted by friends.

In a certain sense we expect to be persecuted by enemies, but it hurts most when it is our own friends who seek our ruin.

The key to maintaining a peaceful heart is to keep the faith and set our eyes on Jesus Christ:

Look then on Jesus, the author and preserver of faith: in complete sinlessness he suffered, and at the hands of those who were his own, and was numbered among the wicked. As you drink the cup of the Lord Jesus – how glorious it is! – give thanks to the Lord, the giver of all blessings.

It may not be easy to be grateful for such a cross of persecution, but when viewed in light of Jesus' cross, we will we able to see how we are united to him in a special way, and how the door to eternity will be opened to those who persevere in faith.

The Traditional Latin Mass Explained

An explanation of the Tridentine Mass by Fr. John Carlisle, FSSPX "It is easier for the earth to exist without the sun, than without the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass" The Traditional Latin Mass is profoundly rich in mystery and symbolism, much of which can easily go unnoticed. With this Solemn High Mass, filmed in Kansas City, Missouri and commented upon by a priest, we hope to unfold some of that mystery to the average Catholic, to help all to grow in appreciation and devotion to this, the greatest treasure of the Church. We share this video in profound gratitude to Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, through whom the Traditional Mass was preserved during this time of crisis in the Church. Filmed in Kansas City, Missouri in September 2024 Celebrated by Fr. Gerard Beck Served and Sung by Seminarians of St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary in Dillwyn, Virginia Commentary by Fr. John Carlisle 0:00:00 Beginning of Mass 0:28:26 The Offertory 0:40:25 The Immolation 0:45:30 The Communion 0:58:01 Thanksgiving and Conclusion If you would like to support the seminary, please consider leaving a donation at: give butter.com/stasdonate

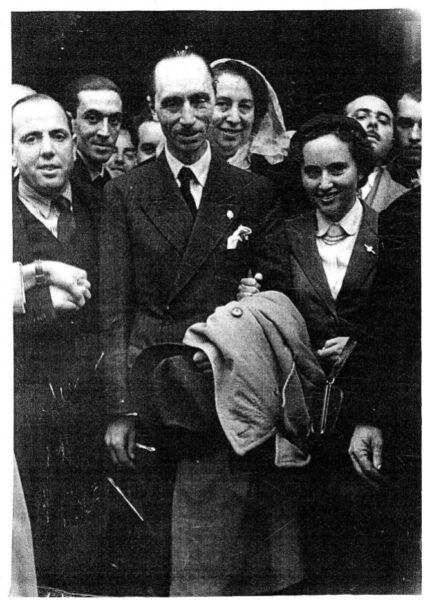

The Everlasting Carlism

I wore a Red Beret for years, because like the Cristeros, the Carlists went into battle with the cry ¡Viva Cristo Rey! on their lips. ¡Dios, Patria y Rey!

From One Peter Five

By Theo Howard

The True Old World

As seen on the latest Mass of the Ages Discover Tradition travel show, when Americans arrive on the Old Continent, and especially Catholics, they express a peculiar fascination. Some attribute this to the historical and architectural condensation of the old world. Or, related to Spain, that the Peninsula is almost a world reduced in scale. The immense variety of geographies and habitats in small areas is a dramatic counterpoint to the vast spaces of the American continent.

But in reality, the historical construction that differentiates them, and causes this admiration, is their worldview. This leaves its mark on their character, way of being, and way of organising themselves as peoples. The 18th, 19th and 20th centuries have happened for everyone. But on the European continent, they occurred as an assault on a very long-lived civilisation: Christendom. Whereas in North America, to quote Tocqueville in Democracy in America, “the thing was new”, truly new.

The admiration then comes from a distant family resemblance. Although one does not know whether that familiarity lies in the classical element or in the revolutionary element. Perhaps it lies in both. Because, throughout the world, it is true that the modern tide has shaken every soul, every house, every village. But the natural and venerable roots have also risen up and survive without being completely subjugated and are never sterile.

This is at the heart of something so common when visiting another country. The resilient survival of nature seeks tradition; a phenomenon that is not understood by those who are shocked that political movements such as monarchical legitimism survive today. Thus, Jacobite remnants in the United Kingdom, or Portuguese Miguelism, but above all, the Carlist defenders of Sixto-Enrique de Borbón in Spain and Spanish America. Mere folklorism, or a romantic affinity for historical re-enactment, cannot explain the courage and dedication, sometimes very sacrificial, of these colourful continuities.

Neither stamp collectors nor lovers of Renaissance clothing consider themselves to be involved in politics. Nor are they a secular survival as an institution in the traditional sense, to whatever degree or intensity. Nor do they provoke the sometimes hostile and dishonest enmity of movements with revolutionary political roots.

Beyond geography, this is the true old world, with religious and natural roots. More than old, it is true in that sense. We see the strong presence of this idea in the backbone of Spanish legitimism, Carlism.

A Different Political Order

We cannot give an exhaustive account of Carlist doctrine here. It must be said that it is the incarnation of the principles of Catholic morality and politics and of natural law, with its peculiar Hispanic concretisation in its customs and traditions. We should also mention the localist and regional aspects, the common union of different regions, the customary flavour of its law, and the protection of the municipality, professional societies, and the weak against the power of the strong or of money.

But let us insist on the aspect of organic order through the natural institutions of society. That authority and obedience be public. That a society of families be crowned in the royal family. That the natural family, municipal, guild, and regional authorities and the King be the face of the political community. These and other elements are opposed to societies atomised into individuals, factions, clandestine influences, and secret powers that seek to change society for their own benefit.

A modern society, or rather a “dissociety,” is divided and manipulable by the worst interests. Even a small, local community, relatively isolated from modern evils and morally healthy, can easily be led to condone or support those evils. This can occur either through voting or preferring the politics of the lesser evil. Such a community is easily vulnerable to those who infiltrate it, know how to dissimulate in an organised manner, and have a hidden loyalty.

The network of natural authorities, with their own ends subordinate to the common good, without excessive powers but with unconditional prerogative in their sphere. This is the remedy offered by Catholic doctrine – which Carlism takes up – to the sociological chaos of the present. Let us draw a comparison with parental authority to discuss the powers of government. The father has the power to fulfil his role, which is the Christian upbringing of his children. He decides what means to use to fulfil it. In this sense, this power is his; no one has given it to him; he has it by virtue of being a father. This does not mean that his authority over his children cannot be excessive, and he cannot stray from his purpose.

In this sense, it is unconditional. Parental authority is not delegated by any social or political institution; it has its source in nature. Thus, the government assumes a conventional form in each case. However, as an institution of government, its authority is not delegated by anyone. Nevertheless, it must always be focused on its purpose, which is the common good.

This fact is not irrelevant. The fact that the King has his authority, that this authority has its scope, means that, for example, he cannot dispose of a subject’s house or rule his family as if it were his own or as if it were his property. In other words, public authority strengthens society, yes. But it also strengthens the societies that comprise it.

All power, or more rightly potestas, is delegated. But not by man, but by God, from the very source of nature. The legitimacy of powers must lie in the naturalness of institutions, including their conventional dimension. Without that reference, it is impossible to distinguish when a power is acting illegitimately. And the truth is that when it is mistakenly understood that all power is delegated by a subjective will, whether of the State or of the Individual, an all-encompassing tyranny can be established.

Legitimacy in Natural Custom

Like all human societies, Spanish society also has its own character and customs. (Some of these treasures are to be observed in the Discover Tradition: Semana Santa broadcast.) Carlism is legitimism in a profound political sense: the power of government is instituted for the common good of society, not for the particular benefit of those who hold power. But it also defends a legal and historical legitimacy: the venerable laws and customs of the Spanish Christian order, which is the root of Spain and Spanish America.

These laws were violated, but never repealed, in 1833, with the usurpation that took place upon the death of Ferdinand VII, although they had already suffered from previous attempts by revolutionaries during the Napoleonic invasion (1808-1814) and the Liberal Triennium (1820-1823). In 1833, Carlism began, later embodied in the Traditionalist Communion, which today is gathered around Prince Don Sixto-Enrique de Borbón.

The solidity of the Spanish Laws of Succession has allowed for uninterrupted royal continuity from the descendants of King Pelayo (718 – initiator of the Reconquista) to the present day. They also allow for the succession of the legitimate claimant to the Spanish throne, Don Sixto-Enrique de Borbón, who is approaching the age of eighty-six and has no direct succession. His Royal Highness has already adopted the appropriate provisions in a document dated 2021, entrusting its execution – even if he were unable to carry it out himself – to certain members of his Political Secretariat.

The dynastic aspect is far from being a fetish or an accessory historical adherence. It is what has allowed the articulation of profound legitimacy, of exercise, into a legitimacy of right that can be embodied in a concrete political reality. It is what has guided the organisation of the Carlist people, as a certain natural continuation of genuine Spain. It is what has enabled the organisation of Spanish Catholics to resist and confront the revolution, and to escape modern dissolution not only, but above all, in the episodes of war that began in 1833, 1846, 1872 and the Crusade of 1936. For almost two centuries, the structures of the Traditionalist Communion served as a refuge and bastion for the Spanish people, who are above all Catholic. Today, perhaps more modest in number, the Traditionalist Communion continues on this path, because it is the Spanish way.

The Relevance of Carlism Today

All social realities with a history behind them are the subject of literary representations of romanticism, even today. But Spanish legitimism is relevant today not only because, for example, it has a Prince who has arranged his succession. The Communion as a whole also has an effectiveness that is less modest than one might think. It has numerous local circles in Spain and carries out training, dissemination and activism work both on social media and on the streets, as well as face-to-face activities. Since the reorganisation of the Political Secretariat of HRH Don Sixto-Enrique de Borbón in 2001, it has grown in quantity, but above all in quality and organisational capacity.

In its expansion, the Communion has spawned notable Circles in practically all Spanish American countries. It also has a Carlist Circle in present-day Texas and a delegation in Florida. The political projects in all these places, in addition to being based on common heritage and continuity, have their own particular focus, as they also do in the regional diversity of Spain.

In the past, Carlism was not free from enemies or attacks, among which we can mention fascist tendencies, Christian democrats, and (liberal) conservatism in archaic guise. These tendencies continue today and sometimes produce dishonest and immoral attacks, as has happened very recently.

The strength of Carlism has always been based on principles rather than numbers. And it was always the strength of these Catholic and monarchist principles that later gave it numbers, as it continues to do today, in an increasing manner.

Don Sixto-Enrique de Borbón, born in Pau (France) in 1940, is currently the last prince of Christendom. He enlisted under an assumed name in the Spanish Legion and fought with the Portuguese Army in the Overseas War in Angola and Guinea. He has travelled throughout Spanish America. He was the only prince who attended the episcopal consecrations of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre in 1988.

His father, Don Javier de Borbón y Braganza (1889-1977), transported a shipment of weapons from Luxembourg to northern Portugal for the Miguelist uprising in the early 20th century. He then launched a peace initiative during the First World War, taking advantage of the fact that his sister Zita had become Empress of Austria. He was later put in charge of leading the Carlist uprising against the Spanish Republic in 1936. A close friend of Pius XII, the latter entrusted him with confidential missions, such as uncovering Masonic infiltration in the Order of Malta. He was also the Order of the Holy Sepulchre’s lieutenant for France.

In today’s Carlism, we can highlight professors José Miguel Gambra and Miguel Ayuso (faculty member of the Roman Forum), along with the former director of Agencia Faro, Luis Infante, who died in 2024, and Father José Ramón García Gallardo, SSPX. We can also mention the Neapolitan historian Dr Maurizio Di Giovine, the Peruvian jurist Fernán Altuve, the Brazilian judge Ricardo Dip and the Colombian ambassador Alejandro Ordóñez as well as their predecessors, professors Rafael Gambra, Francisco Elías de Tejada and Álvaro d’Ors in Spain, José Pedro Galvão de Sousa in Brazil, Osvaldo Lira in Chile, Rubén Calderón Bouchet in Argentina and last but not least former Uruguayan president Juan María Bordaberry. In the United States, professor Frederick D. Wilhelmsen and Brent Bozell (founders of Triumph Magazine and Operation Rescue) were staunch Carlists.

Over two centuries of the Cause, Magín Ferrer, Pedro de Hoz, Cándido Nocedal, Félix Sardá y Salvany (author of Liberalism is a Sin), and Juan Vázquez de Mella, deserve mentioning among many others.