"This is the logical end of a usurious mindset, one that prioritizes immediacy over inheritance, leverage over labor, and short-term relief over long-term stability."

From Crisis

By Drew Blazsik, MA(Econ), MBA(Finance)

Before signing on the dotted line, every Catholic should understand the long-term financial and moral consequences of the 50-year mortgage.

There has been a recent debate in the political realm, and more specifically among Catholics writing at Crisis Magazine, about the proposal of a 50-year mortgage. At the heart of the discussion is a concern shared by all sides: how Catholic families can realistically move toward owning a home rather than remaining permanent renters.

Mike Parrott, who wrote for Crisis Magazine on this topic, has argued that these financial products function primarily to keep families in long-term debt for the benefit of financial institutions rather than the households themselves. He grounds this critique in Catholic social teaching, which holds that economic and social arrangements should be ordered toward the flourishing of the family.

However, some Catholics, such as Jeff Cassman, have argued that these financial products may benefit families by lowering monthly payments. As he puts it, extending the term of the loan “changes the cash-flow profile,” freeing households to pay down credit-card debt, invest in other assets, or cover medical and family needs.

This argument rests on a single assumption: that extending the maturity of a mortgage meaningfully improves a family’s monthly cash-flow position in a way that justifies the additional debt. While I agree with Mike Parrott that an expanding money supply directly drives up home prices—and that our debt-driven monetary system pressures families to take on debt today rather than wait for higher prices tomorrow—the financial validity of the 50-year mortgage itself still needs to be tested.

Those who argue that it makes sense for families to take on debt in order to acquire an asset often point to the logic of buying today before prices rise tomorrow. This way of thinking is not accidental; it is precisely what a debt-based monetary system encourages. By design, such a system requires families to take on debt to maintain liquidity, while legal and tax structures offer preferential treatment to debt holders rather than to savings or outright ownership.

Testing the Financial Case for a 50-Year Mortgage

For this argument to hold, one central claim must be true: that taking on a 50-year mortgage meaningfully improves a family’s monthly cash-flow position through lower payments. Beyond moral considerations, my primary argument here is financial: the case for long-term debt fails on its own terms. Once the numbers are examined, a 50-year mortgage offers little to no benefit. When the additional cost is evaluated using the Blazsik Mortgage Ratio (BMR), the trade-off becomes even clearer—the lifetime cost of the loan overwhelms any modest reduction in monthly payments.

Mortgage Maturity, Risk, and Interest Rates

Because no historical data exists for 50-year mortgage rates in the United States, I adopt a conservative linear approach based on current 15-year and 30-year mortgage rates—5.45 percent and 6.22 percent, respectively—as reported by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED). Lenders charge higher rates for longer maturities because of the risk associated with time. There is a greater chance to default on debt in 50 years than there is in 15 years. Using these two data points, I estimate an incremental increase for each additional five-year term, which implies an approximate rate of 7.25 percent for a 50-year mortgage. To understand why the 30-year mortgage became dominant, it is useful to examine how monthly payments change as loan maturities are extended.

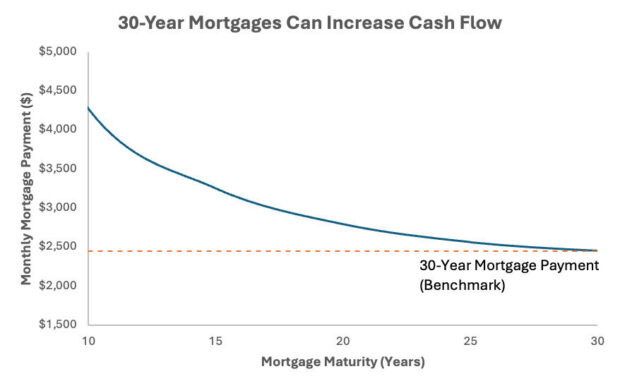

Why the 30-Year Mortgage Became the Standard

When loan terms are extended from shorter maturities toward a 30-year loan, monthly payments fall substantially. This explains why the 30-year mortgage became the standard housing finance instrument in the United States. Up to this point, the cash-flow argument in favor of longer maturities is real and measurable.

Before the 1930s, most U.S. home mortgages had maturities of three to 10 years, required a large down payment, and often involved interest-only payments with the principal due at maturity. Policy changes during the 1930s and 1940s, most notably the creation of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (1933) and the Federal Housing Administration (1934), shifted mortgage lending toward longer terms, eventually normalizing the 30-year mortgage.

For this analysis, I use the average U.S. home price from the Federal Reserve and simply assume a $400,000 mortgage. I also applied the current mortgage rates of 5.45 percent for a 15-year term and 6.22 percent for a 30-year term found on the FRED website. Under these assumptions, the 15-year mortgage produces a monthly payment of $3,258, while the 30-year mortgage results in a payment of $2,455—a difference of approximately $803 per month. This reduction in required monthly payment helps explain why the shift toward the 30-year mortgage was viewed as a financially viable option for households facing affordability constraints.

The Blazsik Mortgage Ratio and the Cost of Time

A clearer way to see the cost of extending a mortgage is through what I call the Blazsik Mortgage Ratio (BMR), which measures the change in total interest paid over the life of the loan divided by the change in monthly payments. If we compare a 15-year to a 30-year mortgage, the BMR is approximately 334. This means that for every one dollar of a reduction in monthly payments, the borrower takes on roughly $334 in additional lifetime interest.A clearer way to see the cost of extending a mortgage is through what I call the Blazsik Mortgage Ratio (BMR), which measures the change in total interest paid over the life of the loan divided by the change in monthly payments.

Why Extending Mortgage Terms Beyond 30 Years Fails

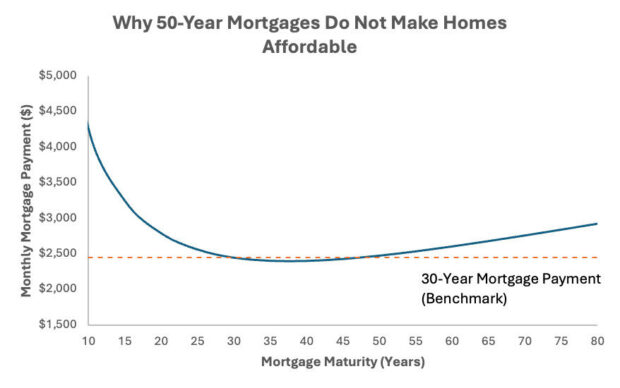

What, then, about a 50-year mortgage? The case for extending maturity rests on the assumption that the same relationship observed between 15- and 30-year loans continues indefinitely. In practice, that assumption fails. The effect of compound interest becomes dominant, and the modest gains in monthly payments that justified earlier extensions no longer materialize. Monthly payments across longer maturities helps explain why extending mortgage terms beyond 30 years fails to deliver meaningful affordability gains.

As interest rates rise with maturity, the payment relief from longer mortgages disappears beyond roughly 35–40 years, at which point longer maturities no longer reduce monthly payments relative to a 30-year loan.

This conclusion does not depend on a moral argument against debt, or even on concerns about obligations being inherited by one’s children, though those concerns are real. Even on strict financial grounds, the structure of a 50-year mortgage fails to deliver meaningful benefits.

Using the same assumptions as before, a 30-year mortgage at an interest rate of 6.22 percent produces a monthly payment of $2,455. Under a reasonable estimate for a 50-year mortgage rate of 7.25 percent, the monthly payment rises to $2,484. In this case, extending the loan term does not reduce the payment at all—it increases it. Rather than improving a family’s cash-flow position, the longer maturity leaves the borrower with less monthly flexibility and substantially greater exposure to compounding interest.

Because the monthly payment is higher rather than lower, the BMR is no longer meaningful in this case. The payment-minimizing effect of extending maturity has already been exhausted. Beyond this point, someone must absorb the growing cost of compound interest over a longer horizon. In practice, that burden falls on the borrower and, increasingly, on the next generation.

Do Lower Interest Rates Change the Conclusion?

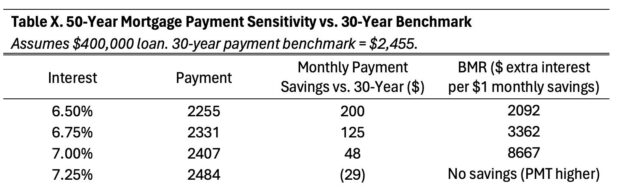

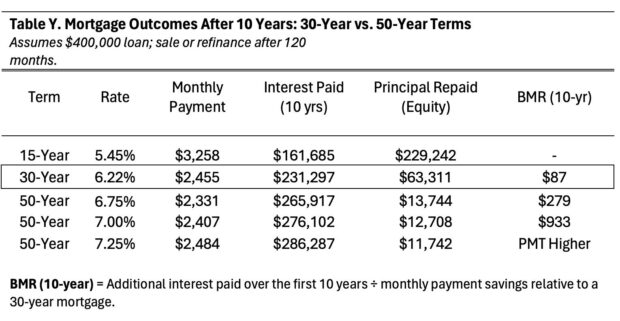

Some may object to the assumed 50-year rate at 7.25 percent. Longer maturity carries greater risk, and lenders historically demand higher rates to compensate for that risk. To test the strength of my analysis, the table below examines several alternative interest-rate assumptions and reports the resulting monthly payments, payment savings or costs relative to a 30-year mortgage, and the corresponding BMR values.

BMR = Total additional interest paid over the life of the loan ÷ monthly payment savings relative to a 30-year mortgage.

(Lower monthly savings correspond to higher BMR values, indicating greater lifetime interest cost per dollar of monthly relief.)

Even if interest rates approached the 30-year rate, a 50-year mortgage is still unconvincing. If the interest rate were as low as 6.5 percent—well below what historical risk premiums would suggest—the monthly payment would fall by roughly $200 compared to a standard 30-year mortgage. But even in this best-case scenario, the trade-off is severe: for every one dollar of monthly payment relief, the borrower takes on more than $2,000 in additional lifetime interest.

As the interest rate rises toward more realistic levels, the cost of that relief escalates rapidly. At 6.75 percent, the monthly savings is about $125, while the lifetime interest cost per dollar of relief jumps sharply. By 7.0 percent, monthly savings falls below $50, yet the additional interest explodes—exceeding $8,000 for each dollar of payment reduction. Once the rate reaches 7.25 percent, the logic collapses entirely: the monthly payment on a 50-year mortgage is higher than on a 30-year loan, eliminating any cash-flow benefit altogether.

In other words, the BMR does not merely worsen as interest rates rise, it breaks down. If we use a more realistic interest rate for our calculations, borrowers no longer experience a trade-off of lower payments for the cost of more interest.

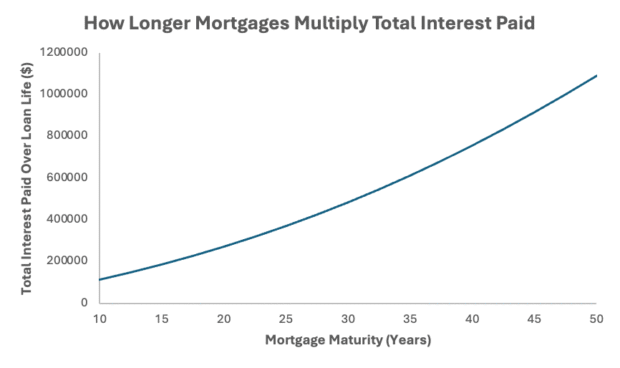

The Hidden Cost: Total Interest and Long-Term Burden

As the maturity of the loan increases, the monthly payments start to flatten, or even eventually rise, and total interest paid over the life of the loan will eventually explode due to compound interest. Under the same $400,000 loan assumption, a 15-year mortgage results in approximately $216,168 in total interest, while a 30-year mortgage results in $483,825. A 50-year mortgage—using the previously discussed interest-rate assumption of 7.25 percent—raises total interest paid to roughly $902,564. In other words, the borrower pays more than twice the original loan amount alone.

This scale of interest accumulation places a heavy burden on families and increases the likelihood that housing debt extends across generations rather than serving as a path to stable ownership.

As mortgage maturity extends, total interest paid rises steeply, particularly at higher interest rates, while offering little additional reduction in monthly payments.

A common response to these figures is that families rarely hold mortgages for the full term of the loan. That is often true. As the calculations indicate under reasonable assumptions for a 50-year mortgage, monthly cash flow does not improve, eliminating the primary justification for extending maturity in the first place. Even if lenders attempted to make such loans more attractive by lowering interest rates, the risk associated with such long horizons would remain substantial.

Equity Accumulation Over a Realistic Time Horizon

In practice, the average mortgage is held for approximately eight to 12 years, depending on economic conditions and region. To evaluate how loan maturity affects real outcomes, it is therefore more relevant to examine equity accumulation over a shorter horizon. The long-term goal of housing finance should be ownership and stability; the short-term strategy of improving cash flow through longer debt obligations often works against that end.

To make the comparison more realistic, assume the home is sold after 10 years rather than held for the full term of the loan. Consider two cases: a 30-year mortgage at an interest rate of 6.22 percent and a 50-year mortgage at an interest rate of 7.25 percent.

Table Y reports interest paid and principal repaid over a 10-year holding period under each loan structure.

The difference becomes even more pronounced once equity accumulation is examined. Under a standard 30-year mortgage at a 6.22 percent interest rate, the borrower would have paid approximately $231,000 in interest while reducing the principal balance by more than $63,000. In other words, after a decade of payments, the family has accumulated meaningful equity.

By contrast, under a 50-year mortgage, equity accumulation is dramatically weaker. At interest rates between 6.75 and 7.25 percent, the borrower pays substantially more interest over the same 10-year period—yet reduces the principal balance by only about $12,000 to $14,000. The 50-year mortgage directly causes ownership to advance far more slowly. Even before accounting for home price appreciation, families trade equity for interest, undermining the very purpose of homeownership.

The Spiritual Formation of Debt

Debt carries a moral and spiritual implication for both individuals and society. Monetary theory is important because the nature of money shapes behavior. When a currency steadily loses value, it encourages borrowing and spending in the present. Over time, such a system pushes households toward debt as a normal condition of economic life. By contrast, a currency increase in value encourages saving, or, historically in the case of gold, hoarding.

The deeper question is what debt does to moral formation. Debt separates reward from work by delivering the benefit immediately while postponing the cost. A simple analogy illustrates the point. If a child is paid before completing a task, the task becomes harder to finish; the reward, and possibly the pleasure, has already been enjoyed. When payment follows the work, effort and reward remain properly ordered. Debt operates similarly, providing instant satisfaction while pushing the burden into the future. That ordering shapes habits and behavior.

Christian tradition understands work not as a burden to be avoided but as a means of a fulfilling life. A life structured around debt trains individuals to minimize present sacrifice in favor of immediate enjoyment. Over time, this disposition has spiritual consequences, forming a preference for ease over discipline and consumption over responsibility.

This helps clarify the Church’s historical teaching on usury. The Fifth Lateran Council defined usury as gain obtained “without any work, any expense, or any risk.” I won’t adjudicate every technical question here; the larger pattern is hard to miss. In modern financial systems, money is largely introduced through lending, profits are generated through interest payments, and returns are often disconnected from productive labor in the real economy.

A debt-centered mindset does not remain confined to consumption; it influences family life as well. Children require time, sacrifice, and long-term commitment. A culture oriented toward minimizing present cost naturally encourages delay of responsibility, delay of family, delay of sacrifice. Christian thought, by contrast, calls for endurance now considering a future good. The horizon is not immediacy but should be eternity. Debt promotes materialism and immediate satisfaction.

It is not an accident that societies with high levels of debt also experience declining birthrates, as families delay having children while their thinking becomes oriented toward immediate financial pressure and short-term satisfaction.

Households that work and save toward a goal tend to value what they acquire because their purchases represent accumulated effort, work, risk, and discipline. Debt obscures that connection by separating enjoyment from cost. The result is not merely a financial outcome but a formative one in the spiritual life.

Why Freedom from Debt Matters for Families

Although I teach through my financial models that paying off a house early is not always the best financial investment, the numbers are not the only factor that matters. Strictly speaking, directing extra cash toward additional mortgage payments is often not the highest return use of capital. However, there are considerations that go beyond spreadsheets and expected returns.

I would argue that if more families were focused on eliminating their mortgage altogether, many would experience greater peace. The fear of losing one’s job, and therefore losing one’s home, is real. Some people are hesitant to speak out, take risks, or change jobs precisely because their mortgage hangs over them. That kind of financial pressure shapes behavior in ways that are often invisible but deeply consequential.

If families did not have to worry as much about a mortgage, property taxes, and other ongoing costs directly tied to their living situation, the result would likely be less stress and greater stability, which would improve family life, encourage larger families, and build a culture that encourages creativity.

Inheritance, Property, and the Purpose of Ownership

Even if a 50-year mortgage did offer modest cash-flow benefits, the idea of placing a long-term financial chain around families is not healthy for society. Rerum Novarum teaches that private property is ordered toward the family and that ownership is not merely a financial preference but a moral and social good. Pope Leo XIII emphasizes that the purpose of property is not endless leverage but stability, independence, and inheritance.

As Leo XIII writes:

It is a most sacred law of nature that a father should provide food and all necessaries for those whom he has begotten; and, similarly, it is natural that he should wish that his children…should be by him provided with all that is needful to enable them to keep themselves decently from want and misery amid the uncertainties of this mortal life. Now, in no other way can a father effect this except by the ownership of productive property, which he can transmit to his children by inheritance.

This teaching makes clear that passing property to one’s children is not incidental, it is central. A society that normalizes permanent indebtedness risks replacing inheritance with obligation. Rerum Novarum further teaches that the family is a true society, possessing rights that are at least equal to those of the State:

A family, no less than a State, is…a true society… Provided the limits which are prescribed by the very purposes for which it exists be not transgressed, the family has at least equal rights with the State in the choice and pursuit of the things needful to its preservation and its just liberty.

How tragic would it be to have a society in which children inherit debt rather than property? It is not difficult to see how a 50-year mortgage makes this outcome increasingly likely. Fathers who never realistically reach ownership may pass on not security but obligation. This is the logical end of a usurious mindset, one that prioritizes immediacy over inheritance, leverage over labor, and short-term relief over long-term stability.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.