This terse announcement touches not only upon the death of a remarkable individual, but of an entire chapter of history not too well known in Europe, and less so in the United States: the relatively short but not inglorious era of the Empire of Brazil. The last time the world press noted its existence was in 2018, when Rio de Janeiro’s former Imperial Palace—the Paço de São Cristóvão, now housing the priceless collections of the National Museum of Brazil—went up in flames thanks to technical incompetence.

The Empire to which Dom Luiz was heir was born in 1822, and in a way very different from the birth of the republics of North and South America. As a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the Portuguese Royal Family, the House of Bragança, had sought refuge in Rio de Janeiro— capital of the then world-spanning Portuguese Empire’s largest possession. In 1821, King John VI returned to the motherland to deal with difficulties, leaving his eldest son Pedro as regent. The following year—partly inspired by the Wars of Independence ravaging Spanish America at that time—a movement arose seeking independence for Brazil. The King advised his son to spare Brazil the bloodshed in their neighbouring countries and take command of the Independence Movement himself. He did so, and in December of 1822 was crowned Pedro I, the first Emperor of Brazil. In order to intervene in Portuguese affairs, Pedro I abdicated in 1831 in favour of his son, Pedro II—a child at the time—and returned home. Pedro II, called “the magnanimous,” came of age in 1840 and presided over the greatest period of progress in Brazilian history. Under his aegis, the country was spared the instability of its neighbours, was respected by both European powers and the United States, and truly entered the modern age. Brazil was victorious in a number of wars, and the Emperor gained a well-deserved reputation as a scholar, sponsoring learning, culture, and the sciences. He was a friend to Richard Wagner, Louis Pasteur, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and many other of the great names of his era.

Despite his popularity, the Emperor had several Achilles’ heels. Having no sons, his heiress was his eldest daughter, Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil. Married to Prince Gaston of Orleans, Count of Eu (and grandson of the usurping and then deposed King of the French, Louis Philippe), she was known to share her father’s distaste for slavery and desire for its abolition, which roused the plantation owners against the Imperial family. Additionally, the republican positivism of August Comte spread amongst the army officers—leading many to oppose both the Monarchy itself and the Princess Imperial’s piety. In 1888, while her father was in Europe seeking medical attention and she was regent, Dona Isabel ordered slavery abolished. Her father returned and approved the measure, but the result was a bloodless military coup in December of the following year. The Imperial family went into exile in Europe, where the Emperor died two years later.

The new republic seized their property and decreed their eternal banishment. There were several monarchist revolts, but the Princess Imperial was as opposed to bloodshed as her father and did not support them; they were quickly suppressed. Brazil’s new republic went on to enjoy a series of governmental mishaps and catastrophes down to the present—in very similar fashion to her neighbours. Dona Isabel’s oldest son, Dom Pedro, renounced his rights in order to marry a non-royal Austrian noblewoman. Her second son, Dom Luís, married Princess Maria Pia of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. He was active in supporting the Brazilian Monarchists until entering World War I; his service therein ruined his health, and he died in 1920. His son, Pedro Henrique, was born in 1909 and assumed headship of the Imperial house when his grandmother died in 1921. In 1937, Pedro Henrique married Princess Maria Elisabeth of Bavaria. The following year, the eldest child of what would be 12 in all, Luiz Gastão Maria José Pio Miguel Gabriel Rafael Gonzaga de Orleans e Bragança was born in Mandelieu-la-Napoule in the south of France. Although the Imperial family underwent great privations during the war, they survived. The ban on their returning to Brazil having been lifted years before, the end of the war meant they could finally return in 1945. Years later, Luiz reminisced about his first sighting, as a seven-year-old, of his ancestral homeland:

Guanabara Bay was wrapped in fog on the morning of our arrival, and so we could only see bits of the wonderful landscape: a bit of the Sugar Loaf and, from time to time, Christ the Redeemer appeared among the clouds, as if to welcome and bless us. However, one more thing impressed me deeply that day: it was the way the Brazilian monarchists, who had come on board to welcome us, greeted my parents and us children. There was something of respect, veneration, and hope, more in their gestures than in their words, that made me feel clearly that I had, like my father, a mission, a duty to the country that I was seeing for the first time. I believe that, for me, it was a grace from God that Rio de Janeiro was covered in mist when we arrived, because it is possible that the panorama of Guanabara, in the light of a beautiful sunny day, would have dazzled me so much that I would not have perceived something much higher, which were the souls of the Brazilians who welcomed us and the duty that this meant for me.

The Imperial Family initially resided in Rio de Janeiro and Petrópolis before moving, in 1950, to the north of the state of Paraná, then Brazil’s great agricultural frontier. In Paraná, they first lived on Fazenda São José, in Jacarezinho, before moving to Fazenda Santa Maria in Jundiaí do Sul in 1957. On those two typically Brazilian farms, Dom Luiz came into contact with the reality of country life, like so many Brazilians of that time. Away from palatial splendor one might expect for a prince, he learned about life and about the deep, authentic Brazil, something that would not have been so easily within his reach had he been born and raised in a royal court.

After receiving a solid education at home, Luiz studied at the schools Coração Eucarístico and Santo Inácio, in Rio de Janeiro, and at Cristo Rei College in Jacarezinho. Speaking fluently Portuguese, French, and German, and understanding Italian, Spanish, and English, he then went to Europe, where he studied political and social sciences at the University of Paris, and later chemistry and physics at the University of Munich. In the sparse free time that the rigid university course allowed him, he took the opportunity to make Brazil better known in the circles of the royalty and the high nobility, and also in the Catholic intellectual circles in Europe.

He returned to Brazil in 1967 with a degree in chemical engineering. Settling in São Paulo, he took over the management of his father’s secretariat, who at the time lived in Sítio Santa Maria in Vassouras, a former coffee-growing center of the Empire in the central southern region of the state of Rio de Janeiro.

The young prince’s moral and religious formation was complemented by Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, eminent Catholic thinker and monarchist, childhood friend of his father, and founder of the Brazilian Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family, and Property (TFP), which Luiz joined upon his return—in order to defend authentically Catholic values and beliefs, and to defend Brazil from the great danger that threatened it, the advance of international communism. In 2006, he was one of the co-founders of the Institute Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira.

When his father died on July 5, 1981, Luiz became Head of the Imperial House, at a time when Brazil was going through the final phase of the military regime. During the constitutional assembly that followed the political climate was favorable to demand consistency from the republican authorities—openness, not only to the Left, but, above all, to the monarchists. The prince, always assisted by his younger brother Dom Bertrand, knew how to skillfully take advantage of the new circumstances, reorganizing his Secretariat and initiating a broad work of linking the countless monarchists that existed in all states of Brazil, from north to south. Under his leadership, the monarchist cause was truly reborn, with a vitality that surprised many who considered it to consist merely of a few nostalgic supporters.

The coat of arms of the princes of Orléans-Bragança, composed of the COA of the Imperial House of Brazil as the

background.

After the National Constituent Assembly was convened in 1987, Luiz sent his “Letter to the Members of the National Constituent Assembly.” In this letter, he showed the senators and deputies who were then drafting the current federal constitution that it was not possible to continue denying a voice to monarchists when even communists and extremist ex-guerrillas freely participated in the public and political life of the country. As a result of his efforts, 366 delegates voted for abolition of the so-called entrenched clause, a constitutional provision that for nearly a century had left monarchists outside the law. There were 29 votes in favor of keeping it and five abstentions. Soon afterwards began the long and laborious campaign of the 1993 referendum, which aimed to consult Brazilians, 104 years late, about Brazil’s form of government: parliamentary monarchy, parliamentary republic, or presidential republic.

Luiz did not think that the time for restoration had come, and he was under no illusions about the referendum’s outcome; he knew that the process would be worked out by the republican authorities, for their own gain. But he nevertheless took advantage of the occasion to spread monarchical ideals throughout Brazil, which has had some fruit down to the present. Although confronted with financial difficulties and unfair restrictions on access to radio and television to popularize his message, Luiz, supported by his brothers, achieved, not a defeat, but a true moral victory. They had proved that the Monarchy was still an alternative and a hope for a large number of Brazilians.

After the referendum, the prince continued his activities, more focused on cultural than political aspects, traveling all over Brazil, participating in Monarchist meetings and related events, always maintaining contact with the real Brazil. Travelling to the United States and Europe, he gave lectures, participated in cultural events, and attended important occasions of the European royalty and high nobility. As rightful Emperor, Luiz sought to address the nation by means of press releases and statements. He also maintained a large correspondence and granted audiences to monarchists from all over Brazil, as well as journalists and other Brazilians who, regardless of party affiliation, wished to learn his opinions on a great variety of issues.

Always aware of his hereditary—and, in his eyes, God-given—obligations, Dom Luiz was also widely read and enjoyed classical music, especially Brazilian Baroque. He was Grand Master of the Brazilian Imperial Orders and member of a number of others, including the Sovereign Military Order of Malta and the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre.

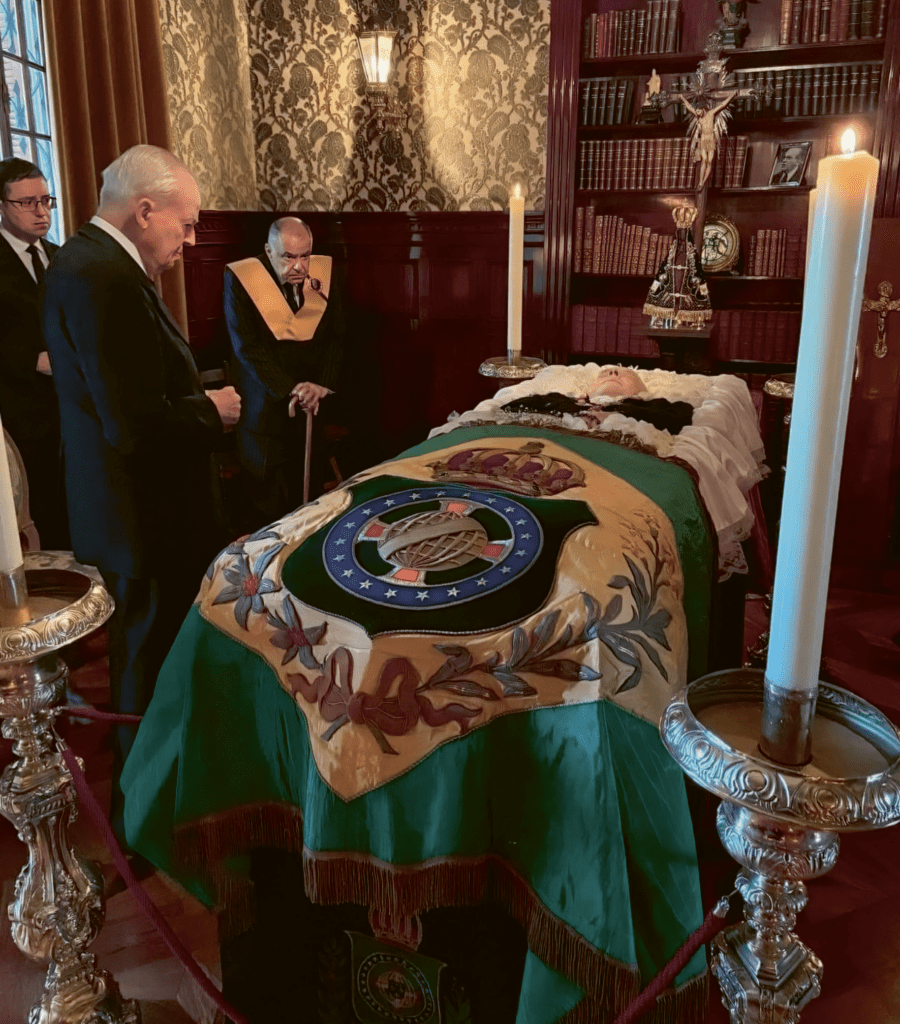

Dom Luiz’s wake took place at the headquarters of the Instituto Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira in Brazil.

At his death, President Jair Bolsonaro decreed official mourning throughout the country: civilian and military institutions throughout Brazil hoisted flags at half-mast in their headquarters and barracks. The federal government, through the Special Secretariat of Social Communication, also paid tribute to Dom Luiz. Several Brazilian states and foreign countries offered condolences. Sympathy notes were sent to the Imperial Family from all over Brazil, the rest of the Americas, and Europe. Expressions of regret came from reigning and former reigning families related to the Imperial Family.

After the funeral mass, in Santa Teresinha Church, his burial, accompanied by hundreds of people, took place in the Consolação Cemetery, in the presence of the Honor Guard of the Brazilian Navy and detachments of the Brazilian Army. Dom Luiz was succeeded as the Head of the Imperial House by his brother, Prince Bertrand. Their brother, Dom Antonio, is now Prince Imperial; his heir presumptive, in turn, is his son, Dom Rafael. They and their followers have surely rededicated themselves to the cause of Restoration in Brazil.

This tribute appears in the Fall 2023 edition of The European Conservative, Number 28:117-120.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.