From One Peter Five

By Whispers of Restoration

NB: See the rest of this series, plus other articles on the same topic here. Readers are also encouraged to acquire a traditional Catholic catechism; see our list, or check Tradivox.

Introduction

The Vatican’s new Directory for Catechesis has received rather scanty attention in the Catholic press (its appearance amid the Covidmadness being likely to blame), but we aim to change that as quickly as possible; because Saints preserve us, this one’s a humdinger. We are aided here by the analysis of one master catechist and educational specialist who has worked in USCCB circles for several years, and will be unpacking their insights in detail over a few installments.

However, even a cursory read reveals this new Directory to be the most concise, comprehensive, and systematic presentation of the core beliefs and methods yet prescribed for the “postconciliar Church,” as it has been called; and in many ways, the Directory is itself a “parallel church catechism.” It may be fairly regarded as a kind of manifesto for what this parallel church believes, how it plans to inculcate those beliefs, and what methods it will adopt for the training of others.

Beyond its sweeping practical implications and not a few doctrinal difficulties (which is perhaps putting it lightly), by far the most troubling aspect of the entire text is its employment of a massive semantic shift, one unprecedented in Catholic catechetical literature. In this, one detects an exercise of what the respected Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira referred to as “unperceived ideological transshipment” – a dimension we will explore further in this mini-series.

Our central claim is that this new Directory is a blueprint for the final evisceration of supernatural faith from any Catholic institution unhappy enough to implement it – which, as the document insists, should be all of them. Let the reader decide if the text bears it out, aware that we undertake this analysis in the hopes of helping others, particularly those entrusted with the care of souls, to both see and act with clarity and conviction.

First, Meet Your Catechists

On June 25, 2020, the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization (PCNE) held a press conference at the Vatican to reveal the new Directory for Catechesis (DC), officially promulgated by Pope Francis on March 23, 2020. The DC is the result of more than one hundred contributing experts (whose names have not been made public), collaborating since early 2015.

The release was chaired by three leaders of the PCNE, pictured above from left to right: Bishop Franz-Peter Tebartz-van Elst (Delegate), Archbishop Jose Octavio Ruiz Arenas (Secretary), and Archbishop Rino Fisichella (President). Although Secretary +Arenas once served on the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (under then-Cardinal Ratzinger) and seems a respectable character, we feel obliged to remind readers that the other two hierarchs pictured above have troubled backgrounds.

As always, we love and pray earnestly for our clergy, and only draw attention to the public scandals recently surrounding these bishops to raise a question: Are these men trustworthy to reshape Catholic catechesis in our time?

President +Fisichella was formerly President of the Pontifical Academy for Life, relocated from that position by Pope Benedict XVI, to the newly-created PCNE in 2010 (some surmising that the PCNE was created for this purpose). This was after major public outcry over a series of statements made by the Archbishop, where he implied the legitimacy of direct abortion in some cases. The situation became so heated that a very unusual step (that is, before CancelChurch) was taken by several prominent members of the Academy: five appealed to the pope to intervene directly and remove +Fisichella from his position, in fear that the Academy was swerving toward moral relativism – fears that seem to have been confirmed since then.

Instead of a removal with disciplinary action, Archbishop Fisichella was promoted to head the new PCNE, where he oversaw the creation of the new Directory for Catechesis and remains today.

Delegate +Tebartz-van Elst was quietly added to the PCNE in 2015, when work on the new Directory first began. Earlier, he had been removed from his diocese due to civil litigation over his scandalous spending habits: having paid a court-ordered fine of nearly $30k to avoid perjury charges (after lying under oath about his luxury first-class flight and “charity trip” to India with his Vicar General) and earning the nickname “Bishop of Bling” – largely for spending roughly $42 million updating his residence and diocesan center. Apparently the renovations included $2.4 million for bronze window frames, $300k for an ornamental fish tank, $350k for a private chapel (which looks like an occult temple of techno-doom), and the grand prize: $22k for a custom French bathtub, which was immortalized in effigy during a town parade.

Although no notable demonstrations of penance have been forthcoming in the years since, the bishop does look barely recognizable since his relocation to the PCNE, where he remains today. One prays he has turned over a new leaf.

For the good of the Church, we feel obliged to pose the question: Should these men be trusted to reshape Catholic catechesis in our time?

“Universal Norms” – Intended Impact

In terms of their theoretical impact on Catholic teaching since the 1970s, it could be argued that few documents have matched the official import of the catechetical Directories of 1971 (GCD) and 1997 (GDC), along with the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC): texts which may be understood respectively as the “methods” and “content” predominant in the Church’s earthly institutions since the Second Vatican Council, or at least since the Vietnam War.

Recognizing that every generally observable trend in the Church since that time has been toward catastrophic loss (or “auto-demolition,” as Pope Paul VI claimed), Catholics are justifiably concerned with precisely what kind of training this new Directory will be prescribing. After all, it is offered as a manual of “universal norms to guide pastors and catechists”[1], held as “indispensable for all those responsible for formal religious instruction”[2], and clearly intended to illustrate the “new normal” for institutional Catholic teaching throughout the world.

In the face of vertiginous statistical collapse in nearly every sector since the above texts were promulgated, the faithful have every right to ask: What manner of norms are our pastors and catechists being given in this newest Directory? What is envisioned for our parishes and schools? Our seminaries? Our parents and children? What exactly does the DC propose for Catholic catechesis on a global scale?

One answer seems readily clear: whatever else it may be, it is very new.

Screenshot from USCCB promo video

The Very New Directory

Far from being a bare revision of the 1997 Directory, the 2020 Directory is an entirely new text, created from scratch over the last five years. Those familiar with the fate of the original document schemas of the Second Vatican Council may detect some similarities here. To quote two of its main architects:

“[The 1997] Directory was examined and the points to be reviewed and updated were noted… [but] it was concluded that it was more appropriate to rework a new Directory” (+Arenas, statement here)“We got the impression it’s not only necessary to work on a revision, but we have to write a totally new text. So we did.” (+Tebartz-van Elst, interview here)

The ostensible warrant for this “totally new text” is of course its current historical context, which the DC frames as an “epochal watershed” (#319), a “change of era” (#38), a dramatic shift “taking place within the horizon of meaning of human experience itself” (#46). Therefore, the Church’s teaching mission must enter a “new stage” (#5, 38, 41); one where “the goal of the catechetical process is reinterpreted” (#3) and the Church is called to “rethink” not only catechesis, but all other “pastoral activities… even the most ordinary and traditional ones” (#303), in order to “find new languages and forms of expression” (#400) as it “strives to keep the Gospel of Jesus Christ relevant” (Preface).

In doing so, rather than ground itself in the enduring Tradition of the Church to face this storm of “profound changes” (#38, 45, 46, 213), the DC opts instead to root its directives in the “ecclesial context of recent decades” (#4) – a period which, it must be said, has been marked by all manner of vicissitude, ambiguity, and error. In point of fact, the DC is so disproportionately indebted to the documents of and since Vatican II, that it would be more aptly entitled the Directory for Postconciliar Catechesis, or even Bergoglian Catechesis.

Analyzing the References

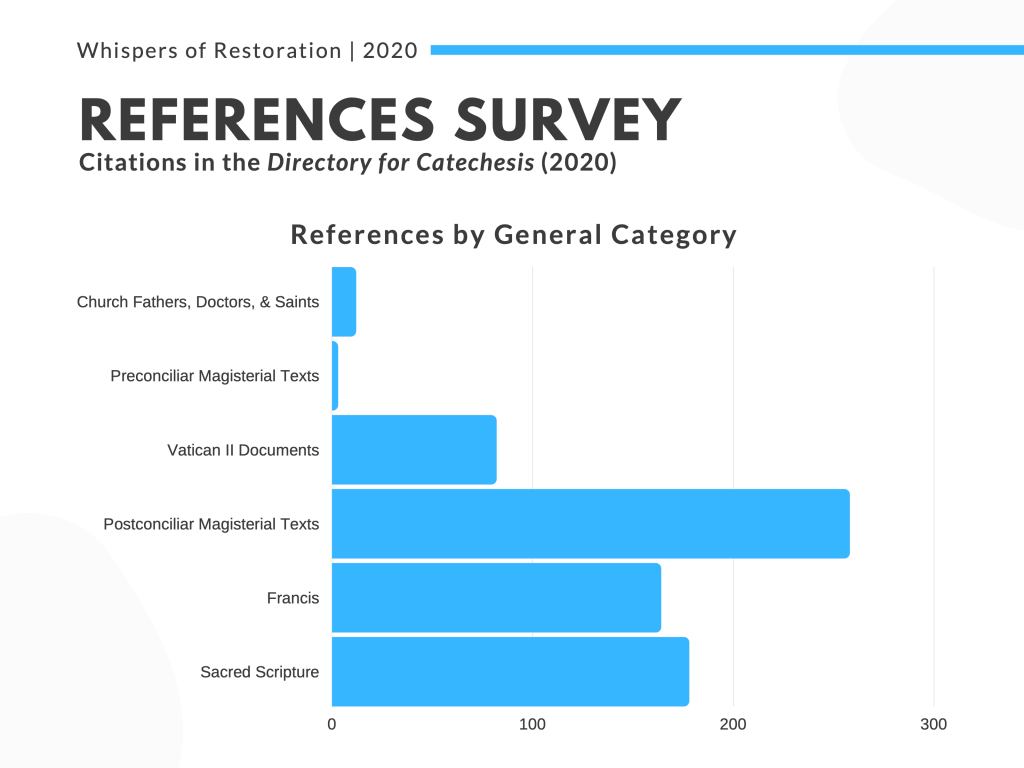

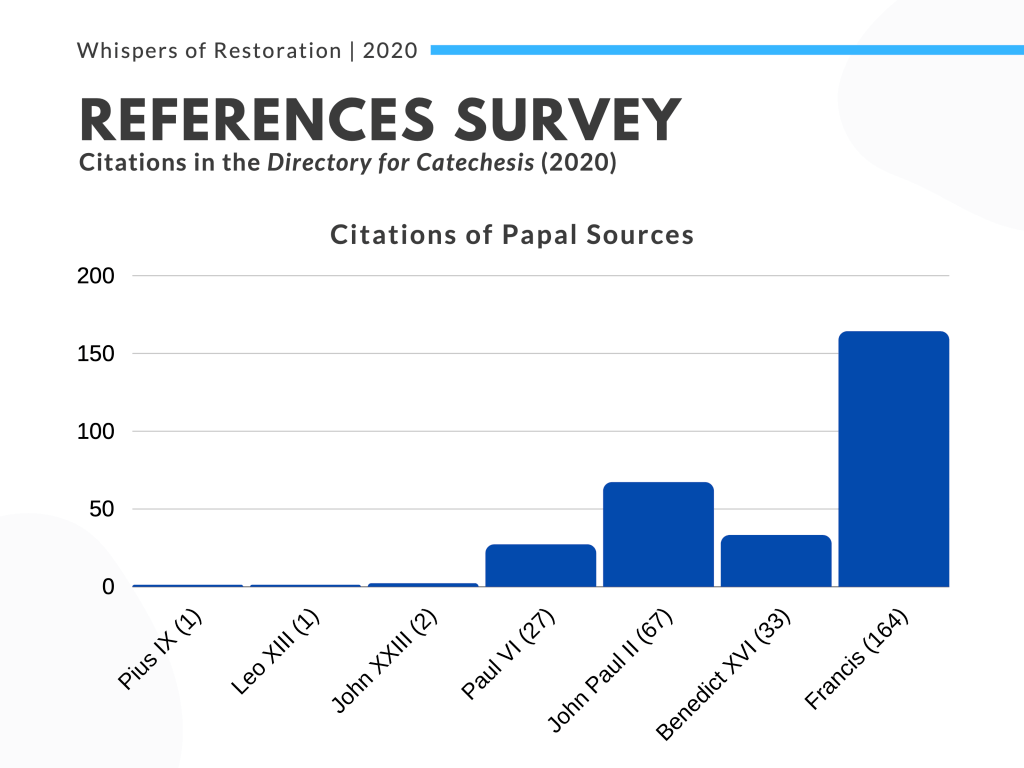

What follows are several visualizations of every citation made in the DC, broken out in various ways. Our method was to tally each of the 706 unique document citations from both the body text and footnotes, allowing for the most precise breakdown of all the DC’s reference material.

One initial point of remark is the DC’s frequent and adulatory references to Vatican II, often referred to simply as “the Council,” and held aloft as il grande catechismo dei tempi nuovi: “the great catechism of modern times” (Preface). Appearing almost sixty years after that council (which clearly failed to bring any flowering in Catholic catechesis – quite the opposite, in fact), it was something of a surprise to find the DC referencing it so often. In total, the DC manages to cite all but three of its sixteen final documents, with nary a qualification or critique, and although it’s unlikely that the editors intended to place the conciliar texts on equal footing with the inspired Word of God, it seems noteworthy that Vatican II is the only source besides Scripture to receive in-text citations. All other sources are footnoted.

Now, on to a survey of the DC’s reference material:

The category of “Church Fathers, Doctors, and Saints” encompasses all citations of non-magisterial works of Catholic theology (all of which predate AD 1960). “Magisterial Text” categories include papal documents, as well as texts promulgated by local, regional, or general Church councils, and any Vatican apparatuses, e.g., Congregations, Commissions, or Pontifical Councils. For convenience, the terms “preconciliar” and “postconciliar” are adopted, to denote the time periods before and after the Second Vatican Council, respectively. Pope Francis’ citations are broken out separately in order to demonstrate the frequency of reference to his thought.

Inasmuch as Scriptural texts can be multivalent (particularly in a Directory concerned principally with methodology), parsing the above data to focus on non-scriptural sources affords greater insight on the DC’s indebtedness and direction.

In doing so, one discovers that, even if the DC had referenced thirty times as many sources from the first one thousand, nine hundred and sixty years of Catholic catechetical praxis, the document would still contain 12% more references to postconciliar sources, those dating from only the past fifty-five years. The DC appears to take very seriously its own exhortation to keep “up-to-date” (#135, 370).

The three most oft-cited sources in the DC, from most to least, are: Scripture, Francis, and Vatican II, in that order. There are 178 citations of Scripture, more than any other single source (although only 14 more than the runner-up). There are 82 citations of Vatican II, which is five times more than all preconciliar source citations combined. No other preconciliar Church councils are cited, although a few postconciliar synods are, and only one other general council gets so much as a mention: when the DC’s Preface recalls the Council of Trent as the progenitor of the first universal Catholic catechism.

The DC’s most-cited individual author, at 164 citations, is Pope Francis. Averaging at least one citation per page spread, Francis’ name is literally all over the DC, with twice as many citations as the documents of Vatican II, and thirty-five more than the other papal citations combined.

Another word must be said about the text’s driving mantra: “NEW.”

Without venturing too far into analysis of the document’s content, it should be noted that, including blank pages and section titles, there are a total of 251 pages of body text in the DC, from Preface to Conclusion. Within that range, the term “new,” including word forms (e.g., newness, renew), occurs 258 times. This means that in the body text, the word “new” occurs more than once per page – even on the blank ones.

Furthermore, terms evoking the sense of novelty and change are found frequently throughout the DC, especially when contrasted with terms connoting the opposite sense of tradition and fixity:

Although semantic analyses are by no means a perfect science and the terms tracked above were not contextually disambiguated, this snapshot fairly reflects the DC’s semantic baseline: just over two-thirds “novelty and change.”

“Creation of a New Language” – Stranger Still

By far the most revealing “raw data” on the DC’s novelty, however, is its alarming lexical range, which we will unpack further in a coming installment. In several places, the DC calls for “the creation of a new language” (Preface, #5, 41, 44, 326, 400), but it certainly doesn’t wait around for that creation: the DC itself marks a seismic shift in Catholic lexicological history. Its pages are so teeming with novel words and phrases, that even attempting to define them all would approach impossibility (which is perhaps why the DC seldom bothers to define its terms, and includes no Glossary).

In truth, the new lexicon so impacts certain sections of the text, that several paragraphs are rendered completely unintelligible. The catechist consulted for this analysis related that one higher-up in a US diocese, upon being asked “What does this mean?” about one of Pope Francis’ phrasings, simply shrugged and responded: “I don’t know.” Here, one may recall a recent word of warning from the former Apostolic Nuncio to the United States:

“[T]he systematic renunciation of the clear, unequivocal and crystalline language of the Church confirms the desire to detach itself not only from the Catholic form but even from its substance.”

(Archbishop Viganò, quoted here)

Despite some recognizably good points, the new Directory has a lot to answer for; and we fully intend to put the DC through its paces here in coming days.

Even from what’s already been shown, what should one make of the Vatican’s claim that this new Directory for Catechesis stands in “dynamic continuity” (Preface) with the Church’s catechetical praxis of the last two millennia? Only that it’s rather long on dynamic, and short on continuity.

Catch you for the next piece,

and Bravo the Restoration!

NOTE: “#” indicates paragraph numbers of the USCCB’s first English edition of the Directory for Catechesis (July, 2020), printed under ISBN 978-1-60137-669-5.

[1] As stated on the USCCB website, and printed on the rear cover of the book itself.

[2] USCCB website. The Directory product page reads, in part: “The Directory will also be indispensable for all those responsible for formal religious instruction, including pastors and parish priests, deacons, lay and religious catechists, and religious education teachers in dioceses, parishes, and schools. The Directory will furthermore aid directors of formation who train the faithful in the forms and means of catechesis, including seminary rectors, directors of formation for the permanent diaconate, and lay ecclesial minster formation program directors.”

This article originally appeared at Whispers of Restoration.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.