From Weird Catholic

By Thomas L. McDonald

Some popular devotions arise as a substitute for something else. The scapular is a cut-down habit. The rosary is a simplified Psalter. The Hours of Our Lady is a smaller Liturgy of the Hours.

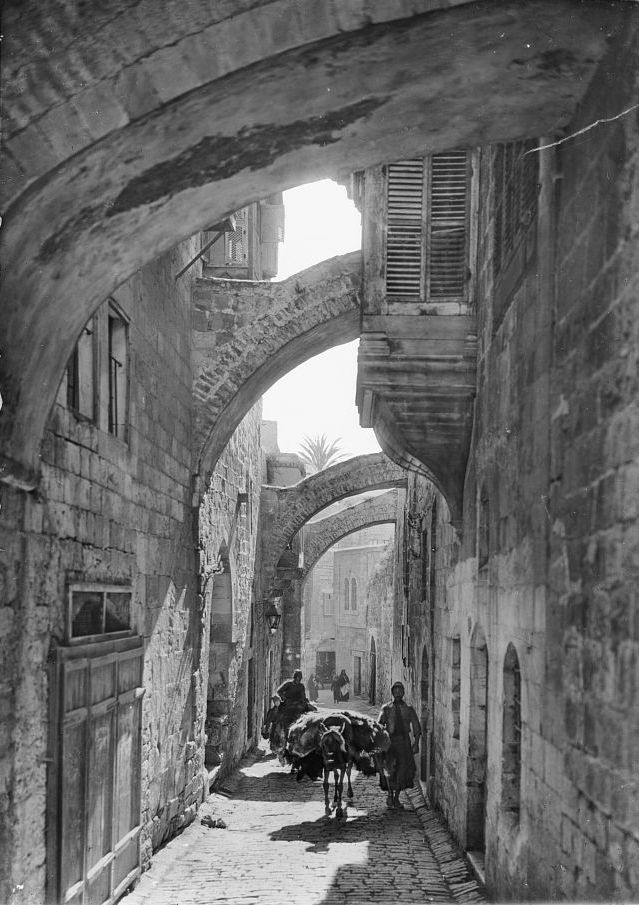

And the Way of the Cross is a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

The idea that the Stations of the Cross developed as European versions of a Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem when pilgrims could no longer safely travel due to the crusades it not quite right. A journey of several thousand miles (one way) was no picnic in the 14th century with or without Ayyubids or treacherous Palaiologoi, and even under the Ottomans some kings were able to negotiate access to Jerusalem. More to the point, the 14 Stations that we know today didn’t assume their final form until long after the last Holy Land crusade, and didn’t have exact corollaries in Jerusalem until after they took form in Europe.

What we find instead is a gradual process of development linked to pilgrimage, but also to piety. Proof that a path known as the Via Dolorosa, marked from early days and already practiced in the time of Constantine, is lacking, and the modern path is aproximate due to two millennia of shifting geography. Indeed, there is nothing in the records of pilgrims of the first ten centuries that includes the Way of the Cross as we know it today.

The memory of locations remained strong with the Christian community, and there is no doubt they knew and revered where certain things happened. The pilgrim known as Egeria, for example, writes in 380 identifying the Church of Anastasis (Holy Sepulchre), Calvary, the Church of Ascension, Gethsemane and the Grotto of Agony, the brook of Cedrom (Kidron), Mt. Zion, and the column of flagellation. There is, however, no mention of any sites not found in the Bible, nor of a devotional path from one to the next.

The Home Pilgrimage

Holy sites were often recreated elsewhere, as with the Church of the Anastasis in Constantinople, or Santa Croce in Rome. San Stefano in Bologna is a complex of churches that forms a “New Jerusalem,” recreating the major shrines related to the crucifixion. In Fabriano, brothers (or cousins) John and Peter returned from Jerusalem in the late 14th century to build a reproduction of the Holy Sepulchre with altars dedicated to the savior crucified (complete with 12 steps called Mt. Calvary), the swoon of Mary, Mary’s grief with pieta, Our Lady of Grace, and a final altar with their remains. In 1420, the Dominican Blessed Alvaro built oratories in his friary to recollect the locations of the passion, which were in turn copied by other religious houses. Blessed Eustochium, a Poor Clare who died in 1491, created representations of various locations, and would walk from place to place reliving the moments of her Savior’s life.

The legend of the Pilgrim nun tells the story of a devout nun who, for a year, made a pilgrimage of the spirit by walking around her convent in silence as though she was making the actual trip. At the end of her journey, she dies in prayer, and a visitor newly returned from he Holy Land claims she accompanied him on his travels.

What we see from these examples and others is the phenomena of the home pilgrimage, informed by a combination of scripture and the written records of those who made the trip. By the late 13th and 14th centuries, the pilgrim accounts begin to offer some hints of a route taken by Christ to Calvary, with certain moments noted. These include the first mentions of the place where Simon helps carry the cross, where Jesus met the weeping women, and where Mary swooned. They are noted as holy places, not as a unified Way of the Cross to follow. The medieval version of a packaged tour also included locations we now associate with the Stations and many we don’t, including a house where the rich man from the parable of Lazarus was supposed to have lived.

By the end of the 14th century, with the Holy Land in the hands of the Turks, pilgrims were locked into the Church of the Sepulchre in the evening, and then in the middle of the night were guided by torchlight to many of the familiar locations in reverse order. The Franciscans maintained tight control over pilgrims, in part in order to get them in and out of the city quickly to avoid conflicts with the Turks.

This peculiar reverse path was eventually attributed to the actions of the Blessed Mother, who would weary herself on a nightly perambulation among all the places visited by her Son in his final hours. We see the first hints of this in some early apocryphal accounts of Mary visiting Christ’s tomb. These were gradually expanded to her wandering to all the locations of his life, including his baptism in the Jordan, his miracles, and others. Dominican theologian Felix Fabri left a detailed account of Mary’s daily journey as it was understood in the 15th century, and if it doesn’t reliably tell us anything about the actions of the Blessed Mother, it tells us a great deal about the piety of the age and how it shaped the Stations of the Cross.

In the pilgrim account of William Wey of Eton College, who travelled to Jerusalem in 1458 and 1462, we find the idea of “statio,” or stopping places, as well as the earliest mention of the place of Veronica’s meeting. Stations begin to appear more regularly into the early 16th century. In 1517, Sir Richard Torkington wrote a description of his visit, lifting his text directly from previous works, but with a new twist: the direction of the “longe way by whiche our Savyour Christe was led unto the place of His crycifyinge” was reversed to follow the path Christ would have travelled. This tells us that shortly before Torkington’s trip, the Franciscans started leading pilgrims in a chronological journey toward, rather than away from, Calvary and the Sepulcher.

The Seven Falls of Christ: A Proto-Stations of the Cross

A key influence on the shaping of the modern stations was the seven reliefs carved about 1490 in Nuremberg by Adam Krafft. These Seven Falls of Christ were widely copied and influenced later depictions as the devotion grew in size and spread. Kraftt’s sculptures were prompted by the pilgrimage of Martin Ketzel, who left an account of his journey. The distance Christ walked from the place of judgment to Calvary became so import to the devotion that Ketzel return to Jerusalem to measure it again after losing his notes. The distance varies considerably from chronicle to chronicle, ranging from 450 paces to 1050 paces. This is another indication that, due to the changing layout of the city, the actual path shifted from age to age.

Booklets featuring a fixed Way of the Cross start appearing at the end of the 15th and early 16th centuries, such as the Dutch “The Journey which our Lord Jesus made from Pilate’s House up to the Mount of Calvary,” which includes 13 stops. Another, published in Nuremberg, has 16. The earliest may be that by Bartholomew, Canon of Pola in Istria, “Considerations upon the Passion of our Lord for those who wish to visit the Holy Places in spiri”t (c. 1480-90). There’s an emphasis on actual distances, in steps, paces (double steps), “ells,” yards, and other measurements between each station, with various psalms, scripture passages, Our Fathers, and Hail Marys specified at each stopping point.

The starting point of these journeys to calvary sometimes vary, with some beginning as Jesus bids farewell to his mother in Bethany, the entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper, or Gethsemane. Henry Suso’s Wisdom’s Watch Upon the Hour, with its meditation of the crucifixion, also grew in popularity.

The starting point of these journeys to calvary sometimes vary, with some beginning as Jesus bids farewell to his mother in Bethany, the entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper, or Gethsemane. Henry Suso’s Wisdom’s Watch Upon the Hour, with its meditation of the crucifixion, also grew in popularity.

One German pamphlet from 1521 begins with the words, “The geistlich [ghostly, or spiritual] way I am called, well known as the Passion of Christ. If you perform this pilgrimage, here are psalms for you to recite; if you want to visit the Holy Land, what you would find there, you can find here.”

Pascha’s Spiritual Pilgrimage

Jan Pascha, Carmelite prior of Louvain, wrote The Spiritual Pilgrimage (1563) as an imaginary journey of 365 days to and from the Holy Land, with particular meditations and prayers on each leg of the journey. In one edition, this includes each day’s travel, such as from Louvain to Tirlemont, Tirlemont to Tongres, and so on to the locations in Jerusalem and back again.

The text was adapted by English translator and printer John Higham, with “from London, or like place” as the starting point. In this version, you come to Jerusalem on the 180th day:

From Silo you shall come to Jerusalem, and before you enter the city, the names of the Pilgrims are registered again, where remember again why thy name was first given thee, and what promise thou made in Baptism.The 181st day, Meditate how many sad and sorrowful steps, Jesus took through the streets of Jerusalem, and how his colour changed passing through the streets, whilst he went there meditating of his bitter passion and torments, and how his most precious blood should be trodden under their vile feet.

With day 188, we begin “Prayers for the voyage of the cross, which are in number 16, which you may say at any other time.” With this, we begin the Way of the Cross proper, done over many days, following the path of Christ from Gethsemane to Calvary.

Pascha’s description of Jerusalem is notable for its details. At the 13th station, on Calvary, he describes what a 16th century pilgrim would have seen:

At an altar in the choir, is a place where the wicked played at dice for Christ’s garments, at which place our blessed Lady and Magdalen did greatly sorrow. On the left hand it is where the Jews prepared the vinegar and gall. In a Chapel under the ground is the place where Saint Helen was wont to pray, and where she died, and was first buried, but after was translated to Venice. Yet deeper is the place where Saint Helen found the three crosses, and three nails, and the Crown of Thorns. Ascending on another Altar thou shalt find under the same a short pillar, where on our Lord did sit when the crown of thorns was put on his head. Now you ascend the mount of Calvary which is a white rock there is a fair Church or Chapel which is all gilded with gold and azure, and is paved with marble. On the one side there is the place where our Lord was hanged on the cross into this place few people do enter. By the door there is the hole of the holy Cross all open two feet deep, and a space broad, into which you may put your arm.

By this point in history discrepancy in the practice of the Stations of the Cross in Europe and the pilgrim trail in Jerusalem is mostly attributable to the starting point, the counting of falls, the separation or blending of incidents, and the demands of pious practice. For example, in some pilgrim accounts the first fall and the meeting of Mary happen in the same place and are sometimes counted as one stop, in others as two. (Today, they are two.) The blending of the Seven Falls devotion with the Way of the Cross thus allows room for all seven falls, if Jesus is considered to have fallen at stations four (Mary), five (Simon), six (Veronica), seven (the weeping women), or upon reaching the summit of Calvary.

Christian Kruik van Adrichem made a widely circulated and adapted map of the Holy Land that marked the path of Jesus through Jerusalem and the locations of various incidents. The map was published around 1584, with data derived from various sources, since van Adrichem probably never made it to Jerusalem himself.

By the close of that century, travel to the Holy Land was becoming more challenging under the Turks, even with deals like the Capitulations of 1604. These difficulties made the devotion easier to carry out at purpose-built stations in Europe rather than in the fractious political climate of Jerusalem itself. Little Jerusalems could be raised at pilgrim sites closer to home, and eventually in every parish church.

These myriad influences flow together to form the shape of the Stations through a combination of travelogues, art, legend, history, and piety. Nuremberg and Louvain in particular helped fix the form in stone, while printed devotional texts and maps helped that form spread.

The devotion, in turn, influenced the experience of pilgrims, who came to expect 14 stops on the Jerusalem path. This isn’t to say the path and the stops have no historical grounding, but merely that their format was shaped by the needs and expectations of the faithful. This began to occur as early as the 17th century, when the descriptions and enumeration of the European stations begin to influence the way Franciscans in the Holy Land presented the sites to pilgrim.

The 14 stations we practice today took root and spread for a very simple reason: they were indulgenced. The Franciscan guardians of the Holy Land adopted this format, and beginning with Innocent XI the faithful could merit an indulgence by performing it. At first the indulgence was limited to the Holy Land, then to Franciscan churches, followed by churches where stations were erected on the authority of Franciscans, and finally to any churches following the proper format.

Only three elements were necessary for the indulgence: meditation on the passion, moving from station to station, and visiting all four without interruption. Subsequent indulgences would reduce the need to move from station to station so people could remain in their pews and follow the procession mentally. In performing the devotion this way, the faithful achieved all the spiritual benefits guaranteed to those who made a full pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

As an aid in drawing the faithful closer to God, the Way of the Cross has long been considered a deeply meaningful practice, and is no less meaningful if, for example, there is no scriptural or historical basis for a particular place where Veronica knelt. It’s never been the stone that counts, but rather the true image—the vera eikon—toward which the stone and Veronica direct the heart.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.