'Like the person of Christ Himself, which it represents, the Sacred Heart approaches us in many ways and elicits from us many responses.'

By Stephen Beale

Like the person of Christ Himself, which it represents, the Sacred Heart approaches us in many ways and elicits from us many responses.

The Sacred Heart is one of the most recognizable of Catholic devotional images. But there is no one standard way of depicting it. In fact, the visual representation of the Sacred Heart has developed dramatically over time.

The devotion as we know it today got its start with a series of visions received by the French mystic nun St. Margaret Mary Alacoque in the late 1600s. But the devotion’s roots run much deeper into the early history of the Church.

Launch this slideshow of how images of the Sacred Heart evolved over time: Launch the slideshow

The history of the Sacred Heart in art properly begins with images of the piercing of Christ’s side, because the spear is understood to have wounded His heart. This scene was captured in some of the early art of the Church. One such image is found in the Rabula Gospels, which date to 586.

But even in the early Church the heart was shown as an independent organ, separate from the body, as in this image from African pottery in the mid-400s. Examples of the heart itself can also be found in a late medieval prayer book and Renaissance engraving, from around 1500 and the late 16th century, respectively,—well before St. Margaret Mary’s visions (source: The Sacred Heart of Jesus by Peter N. Névraumont).

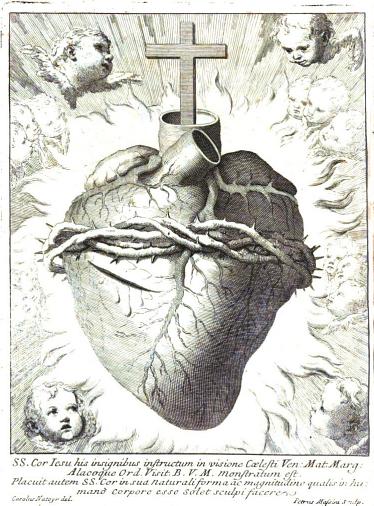

In her mystical encounters with Jesus in the 1670s, the definitive features of Sacred Heart as we know it were revealed to St. Margaret Mary—the cross set in the top, the encircling crown of thorns, and the open wound on one side.

Early renditions of the Sacred Heart after that date emphasize its fleshly reality. In the frontpiece illustration for De Cultu Sacrosancti Cordis Dei ac Domini Nostri Jesu Christi, by Charles-Joseph Natoire 1726, the Sacred Heart is shown in intensely realistic detail, almost like what one might expect from a medical textbook of the time, according to art historian Simonetta Marin (see her article here).

In some instances, the Sacred Heart was displayed apart from the crucified body of Christ but with the figure of St. Margaret Mary, such as this 1765 oil painting of the saint, kneeling before a darkly knotted Sacred Heart in the foreground. That date also marks the year that the Vatican instituted the Feast of the Sacred Heart.

But towards the end of the century, images of the Sacred Heart underwent a dramatic shift from focusing on the heart itself to displaying it with the figure of Jesus, according to scholar David Morgan.

This new development is exemplified in by the small painting of Jesus with His Sacred Heart in the Church of the Gesu in Rome in 1767 by Pompeo Batoni. In the painting, Jesus is wearing a red tunic with a blue cloak wrapped on his shoulders—traditional colors signifying His Passion, or humanity, and His royalty or divinity, respectively. He is holding His heart out to the person viewing the image, almost as some sort of invitation.

As art historian Jon Seydl puts it, it “engages the beholder in a deeply personal exchange that stands outside space and time. Christ’s outward gaze, locking eyes with the beholder, cements this relationship” (quoted by David Morgan in the Sacred Heart of Jesus: The Visual Evolution of a Devotion, 16).

Batoni’s style remained influential into the 19th century, even as other artists made two significant modifications. In both, the heart has moved from Jesus’ hand to His chest. In one version, He is pulling back His outer clothing to reveal the Sacred Heart. In the other, He is pointing to it, according to Morgan.

“The disclosure reenacts the intimate revelation to Alacoque, in effect, sharing his heart with all believers. But it changed the way that people engaged with the Sacred Heart. It was no longer a bloody device signaling penitential suffering, but a gentle, inviting portrait of a benign savior who welcomed an intimate relationship with the devotee, and in less visceral terms than Batoni’s influential image,” Morgan writes (Sacred Heart of Jesus, 23).

There are two other major stages in the history of the Sacred Heart in devotional art, according to Morgan. One came closer to the end of the 19th century and is associated with the practice of enthroning an image of the Sacred Heart in one’s home or other space. These images represent a return to the organic heart, except anatomical realism has been replaced with a more idealized form, more closely resembling Valentine hearts, according to Morgan. (Here is one example.)

A second development can be seen in statues of the figure of Jesus with His Sacred Heart. “The gestures vary, but fall into a few clear categories arms outspread; arms displaying palms, usually bearing wounds; and hands configured in a gesture of benediction, teaching, or presentation of the heart,” Morgan writes (Sacred Heart of Jesus, 32).

Fittingly like the person of Christ Himself, which it represents, the Sacred Heart approaches us in many ways and elicits from us many responses. For example, those images which emphasize its wounded carnality call us to repentance. But Jesus also holds out His Sacred Heart to us as both an offering and an invitation to encounter His love for us.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Francis as the Vicar of Christ (I know he's a material heretic and a Protector of Perverts, and I definitely want him gone yesterday! However, he is Pope, and I pray for him every day.), the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.