Both St Paul of Thebes and St John Calabytes, are venerated today in both the West and the East.

St Paul

From the West:

From Fr Alban Butler's Lives of the Saints

ELIAS and St. John the baptist sanctified the deserts, and Jesus Christ himself was a model of the eremitical state during his forty day’s fast in the wilderness; neither is it to be questioned that the Holy Ghost conducted the saint of this day, though young, into the desert, and was to him an instructor there: but it is no less certain, that an entire solitude and total sequestration of one’s self from human society, is one of those extraordinary ways by which God leads souls to himself, and is more worthy of our admiration, than calculated for imitation and practice; it is a state which ought only to be embraced by such as are already well experienced in the practices of virtue and contemplation, and who can resist sloth and other temptations, lest instead of being a help, it prove a snare and stumbling-block in their way to heaven. 1

This saint was a native of the Lower Thebais in Egypt, and had lost both his parents when he was but fifteen years of age: nevertheless he was a great proficient in Greek and Egyptian learning, was mild and modest, and feared God from his earliest youth. The bloody persecution of Decius disturbed the peace of the church in 250; gad what was most dreadful, Satan by his ministers, sought not so much to kill the bodies, as by subtle artifices and tedious tortures to destroy the souls of men. Two instances are sufficient to show his malice in this respect: A soldier of Christ, who had already triumphed over the racks and tortures, had his whole body rubbed over with honey, and was then laid on his back in the sun, with his hands tied behind him, that the flies and wasps, which are quite intolerable in hot countries, might torment and gall him with their stings. Another was bound with silk cords on a bed of down, in a delightful garden, where a lascivious woman was employed to entice him to sin; the martyr, sensible of his danger, bit off part of his tongue and spit it in her face, that the horror of such an action might put her to flight, and the smart occasioned by it be a means to prevent, in his own heart, any manner of consent to carnal pleasure. During these times of danger, Paul kept himself concealed in the house of another; but finding that a brother-in-law was inclined to betray him, that he might enjoy his estate, he fled into the deserts. There he found many spacious caverns in a rock, which were said to have been the retreat of money-coiners in the days of Cleopatra, queen of Egypt. He chose for his dwelling a cave in this place, near which were a palm-tree 1 and a clear spring; the former by its leaves furnished him with raiment, and by its fruit with food; and the latter supplied him with water for his drink. 2

Paul was twenty-two years old when he entered the desert. His first intention was to enjoy the liberty of serving God till the persecution should cease; but relishing the sweets of heavenly contemplation and penance, and learning the spiritual advantages of holy solitude, he resolved to return no more among men, or concern himself in the least with human affairs, and what passed in the world: it was enough for him to know that there was a world, and to pray that it might be improved in goodness. The saint lived on the fruit of his tree till he was forty-three years of age, and from that time till his death, like Elias, he was miraculously fed with bread brought him every day by a raven. His method of life, and what he did in this place during ninety years, is unknown to us: but God was pleased to make his servant known a little before his death. 3

ELIAS and St. John the baptist sanctified the deserts, and Jesus Christ himself was a model of the eremitical state during his forty day’s fast in the wilderness; neither is it to be questioned that the Holy Ghost conducted the saint of this day, though young, into the desert, and was to him an instructor there: but it is no less certain, that an entire solitude and total sequestration of one’s self from human society, is one of those extraordinary ways by which God leads souls to himself, and is more worthy of our admiration, than calculated for imitation and practice; it is a state which ought only to be embraced by such as are already well experienced in the practices of virtue and contemplation, and who can resist sloth and other temptations, lest instead of being a help, it prove a snare and stumbling-block in their way to heaven. 1

This saint was a native of the Lower Thebais in Egypt, and had lost both his parents when he was but fifteen years of age: nevertheless he was a great proficient in Greek and Egyptian learning, was mild and modest, and feared God from his earliest youth. The bloody persecution of Decius disturbed the peace of the church in 250; gad what was most dreadful, Satan by his ministers, sought not so much to kill the bodies, as by subtle artifices and tedious tortures to destroy the souls of men. Two instances are sufficient to show his malice in this respect: A soldier of Christ, who had already triumphed over the racks and tortures, had his whole body rubbed over with honey, and was then laid on his back in the sun, with his hands tied behind him, that the flies and wasps, which are quite intolerable in hot countries, might torment and gall him with their stings. Another was bound with silk cords on a bed of down, in a delightful garden, where a lascivious woman was employed to entice him to sin; the martyr, sensible of his danger, bit off part of his tongue and spit it in her face, that the horror of such an action might put her to flight, and the smart occasioned by it be a means to prevent, in his own heart, any manner of consent to carnal pleasure. During these times of danger, Paul kept himself concealed in the house of another; but finding that a brother-in-law was inclined to betray him, that he might enjoy his estate, he fled into the deserts. There he found many spacious caverns in a rock, which were said to have been the retreat of money-coiners in the days of Cleopatra, queen of Egypt. He chose for his dwelling a cave in this place, near which were a palm-tree 1 and a clear spring; the former by its leaves furnished him with raiment, and by its fruit with food; and the latter supplied him with water for his drink. 2

Paul was twenty-two years old when he entered the desert. His first intention was to enjoy the liberty of serving God till the persecution should cease; but relishing the sweets of heavenly contemplation and penance, and learning the spiritual advantages of holy solitude, he resolved to return no more among men, or concern himself in the least with human affairs, and what passed in the world: it was enough for him to know that there was a world, and to pray that it might be improved in goodness. The saint lived on the fruit of his tree till he was forty-three years of age, and from that time till his death, like Elias, he was miraculously fed with bread brought him every day by a raven. His method of life, and what he did in this place during ninety years, is unknown to us: but God was pleased to make his servant known a little before his death. 3

The great St. Antony, who was then ninety years of age, was tempted to vanity, as if no one had served God so long in the wilderness as he had done, imagining himself also to be the first example of a life so recluse from human conversation: but the contrary was discovered to him in a dream, the night following, and the saint was at the same time commanded, by Almighty God, to set out forthwith in quest of a perfect servant of his, concealed in the more remote parts of those deserts. The holy old man set out the next morning in search of the unknown hermit. St. Jerom relates from his authors, that he met a centaur, or creature not with the nature and properties, but with something of the mixed shape of man and horse, 2 and that this monster, or phantom of the devil, (St. Jerom pretends not to determine which it was,) upon his making the sign of the cross, fled away, after having pointed out the way to the saint. Our author adds, that St. Antony soon after met a satyr, 3 who gave him to understand that he was an inhabitant of those deserts, and one of that sort whom the deluded Gentiles adored for gods. Saint Antony, after two days and a night spent in the search, discovered the saint’s abode by a light that was in it, which he made up to. Having long begged admittance at the door of his cell, St. Paul at last opened it with a smile: they embraced, called each other by their names, which they knew by divine revelation. St. Paul then inquired whether idolatry still reigned in the world? While they were discoursing together, a raven flew towards them, and dropped a loaf of bread before them. Upon which St. Paul said, “Our good God has sent us a dinner. In this manner have I received half a loaf every day these sixty years past; now you are come to see me, Christ has doubled his provision for his servants.” Having given thanks to God, they both sat down by the fountain; but a little contest arose between them who should break the bread; St. Antony alleged St. Paul’s greater age, and St. Paul pleaded that Antony was the stranger; both agreed at last to take up their parts together. Having refreshed themselves at the spring, they spent the night in prayer. The next morning St. Paul told his guest that the time of his death approached, and that he was sent to bury him, adding, “Go and fetch the cloak given you by St. Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, in which I desire you to wrap my body.” This he might say with the intent of being left alone in prayer, whilst he expected to be called out of this world; as also that he might testify his veneration for St. Athanasius, and his high regard for the faith and communion of the Catholic church, on account of which that holy bishop was then a great sufferer. St. Antony was surprised to hear him mention the cloak, which he could not have known but by divine revelation. Whatever was his motive for desiring to be buried in it, St. Antony acquiesced to what was asked of him: so, after mutual embraces, he hastened to his monastery to comply with St. Paul’s request. He told his monks that he, a sinner, falsely bore the name of a servant of God; but that he had seen Elias and John the Baptist in the wilderness, even Paul in Paradise. Having taken the cloak, he returned with it in all haste, fearing lest the holy hermit might be dead, as it happened. Whilst on his road, he saw his happy soul carried up to heaven, attended by choirs of angels, prophets, and apostles. St. Antony, though he rejoiced on St. Paul’s account, could not help lamenting on his own, for having lost a treasure so lately discovered. As soon as his sorrow would permit, he arose, pursued his journey, and came to the cave. Going in, he found the body kneeling, and the hands stretched out. Full of joy, and supposing him yet alive, he knelt down to pray with him, but by his silence soon perceived he was dead. Having paid his last respects to the holy corpse, he carried it out of the cave. Whilst he stood perplexed how to dig a grave, two lions came up quietly, and as it were mourning; and tearing up the ground, made a hole large enough for the reception of a human body. St. Antony then buried the corpse, singing hymns and psalms, according to what was usual and appointed by the church on that occasion. After this he returned home praising God, and related to his monks what he had seen and done. He always kept as a great treasure, and wore himself on great festivals, the garment of St. Paul, of palm-tree leaves patched together. St. Paul died in the year of our Lord, 342, the hundred and thirteenth year of his age, and the ninetieth of his solitude, and is usually called the first hermit, to distinguish him from others of that name. The body of this saint is said to have been conveyed to Constantinople, by the emperor Michael Comnenus, in the twelfth century, and from thence to Venice in 1240. 4 Lewis I. King of Hungary, procured it from that republic, and deposited it at Buda, where a congregation of hermits under his name, which still subsists in Hungary, Poland, and Austria, was instituted by blessed Eusebius of Strigonium, a nobleman, who, having distributed his whole estate among the poor, retired into the forests; and being followed by others, built the monastery of Pisilia, under the rule of the regular canons of St. Austin. He died in that house, January the 20th, 1270. 4

St. Paul, the hermit, is commemorated in several ancient western Martyrologies on the 10th of January, but in the Roman on the 15th, on which he is honoured in the anthologium of the Greeks. 5

An eminent contemplative draws the following portraiture of this great model of an eremitical life; 5 St. Paul, the hermit, not being called by God to the external duties of an active life, remained alone, conversing only with God, in a vast wilderness, for the space of nearly a hundred years, ignorant of all that passed in the world, both the progress of sciences, the establishment of religion, and the revolutions of states and empires; indifferent even as to those things without which he could not live, as the air which he breathed, the water he drank, and the miraculous bread with which he supported life. What did he do? say the inhabitants of this busy world, who think they could not live without being in a perpetual hurry of restless projects; what was his employment all this while? Alas! ought we not rather to put this question to them; what are you doing whilst you are not taken up in doing the will of God, which occupies the heavens and the earth in all their motions? Do you call that doing nothing which is the great end God proposed to himself in giving us a being, that is, to be employed in contemplating, adoring, and praising him? Is it to be idle and useless in the world, to be entirely taken up in that which is the eternal occupation of God himself, and of the blessed inhabitants of heaven? What employment is better, more just, more sublime, or more advantageous than this, when done in suitable circumstances? To be employed in any thing else, how great or noble soever it may appear in the eyes of men, unless it be referred to God, and be the accomplishment of his holy will, who in all our actions demands our heart more than our hand, what is it, but to turn ourselves away from our end, to lose our time, and voluntarily to return again to that state of nothing out of which we were formed, or rather into a far worse state? 6

Note 1. Pliny recounts thirty-nine different sorts of Palm-trees, and says that the best grow in Egypt, which are ever green, have leaves thick enough to make ropes, and a fruit which serves in some places to make bread. [back]

Note 2. Pliny, l. 7. c. 3. and others, assure us that such monsters have been seen. Consult the note of Rosweide. [back]

Note 3. The heathens might feign their gods of the woods, from certain monsters sometimes seen. Plutarch, in his life of Sylla, says, that a satyr was brought to that general at Athens; and St. Jerom tells us, that one was shown alive at Alexandria, and after its death was salted and embalmed, and sent to Antioch, that Constantine the Great might see it. [back]

Note 4. See the whole history of this translation, published from an original MS. by F. Gamans, a Jesuit, inserted by Bollandus in his collection. [back]

Note 5. F. Ambrose de Lombez, Capuchin, Tr. de la Paix Intérieure (Paris, 1758.) p. 372. [back]

Dom Prosper Gueranger:

Today the Church honours the memory of one of those men who were expressly chosen by God to represent the sublime detachment from all things, which was taught to the world by the example of the Son of God born in a cave at Bethlehem. Paul the Hermit so prized the poverty of his Divine Master that he fled to the desert where he could find nothing to possess and nothing to covet. He had a mere cavern for his dwelling. A palm tree provided him with food and clothing, a fountain gave him with which to quench his thirst, and Heaven sent him his only luxury, a loaf of bread brought to him daily by a crow. For 60 years did Paul thus serve, in poverty and in solitude, that God who was denied a dwelling on the Earth He came to redeem and could have but a poor stable in which to be born. But God dwelt with Paul in his cavern, and in him began the Anchorites, that sublime race of men who, the better to enjoy the company of their God, denied themselves not only the society, but the very sight, of men. They were the Angels of Earth in whom God showed forth, for the instruction of the rest of men, that He is powerful enough and rich enough to supply the wants of His creatures who indeed have nothing but what they have from Him.

The Hermit, or Anchoret, is a prodigy in the Church, and it behoves us to glorify the God who has produced it. We ought to be filled with astonishment and gratitude at seeing how the Mystery of a God made Flesh has so elevated our human nature as to inspire a contempt and abandonment of those earthly goods which heretofore had been so eagerly sought after.

The two names, Paul and Antony, are not to be separated: they are the two Apostles of the Desert. Both are Fathers — Paul of Anchorites, and Antony of Cenobites. The two families are sisters, and both have the same source, the My stery of Bethlehem. The sacred Cycle of the Church’s year unites, with only a day between their two Feasts these two faithful disciples of Jesus in His crib.

*****

Father and Prince of Hermits, you are now contemplating in all His glory that God whose weakness and lowliness you studied and imitated during the sixty years of your desert-life: you are now with Him in the eternal union of the Vision. Instead of your cavern where you spent your life of unknown penance, you have the immensity of the Heaven for your dwelling. Instead of your tunic of palm leaves, you have the robe of Light. Instead of the pittance of material bread, you have the Bread of eternal life. Instead of your humble fountain, you have the waters which spring up to eternity, filling your soul with infinite delights. You imitated the silence of the Babe of Bethlehem by your holy life of seclusion. Now your tongue is for ever singing the praises of this God, and the music of infinite bliss is for ever falling on your ear. You did not know this world of ours, save by its deserts, but now you must compassionate and pray for us who live in it. Speak for us to our dear Jesus . Remind Him how He visited it in wonderful mercy and love. Pray His sweet blessing upon us, and the graces of perfect detachment from transitory things, love of poverty, love of prayer and love of our heavenly country.

From the East:

Saint Paul of Thebes was born in Egypt around 227 in the Thebaid of Egypt. Left orphaned, he suffered many things from a greedy relative over his inheritance. During the persecution against Christians under the emperor Decius (249-251), Saint Paul learned of his brother-in-law’s insidious plan to deliver him into the hands of the persecutors, and so he fled the city and fled into the wilderness.

Settling into a mountain cave, Saint Paul dwelt there for ninety-one years, praying incessantly to God both day and night. He sustained himself on dates and bread, which a raven brought him, and he clothed himself with palm leaves.

Saint Anthony the Great (January 17), who also lived as an ascetic in the Thebaid desert, had a revelation from God concerning Saint Paul. Saint Anthony thought that there was no other desert dweller such as he. Then God said to him, “Anthony, there is a servant of God more excellent than you, and you should go and see him.”

Saint Anthony went into the desert and came to Saint Paul’s cave. Falling to the ground before the entrance to the cave, he asked to be admitted. The Elders introduced themselves, and they embraced one another. They conversed through the night, and Saint Anthony revealed how he had been led there by God. Saint Paul disclosed to Saint Anthony that for sixty years a bird had brought him half a loaf of bread each day. Now the Lord had sent a double portion in honour of Saint Anthony’s visit. The next morning, Saint Paul spoke to Anthony of his approaching death and instructed him to bury him. He also asked Saint Anthony to return to his monastery and bring back the cloak he had received from Saint Athanasius. He did not really need a garment but wished to depart from his body while Saint Anthony was absent.

As he was returning with the cloak, Saint Anthony beheld the soul of Saint Paul surrounded by angels, prophets, and apostles, shining like the sun and ascending to God. He entered the cave and found Abba Paul on his knees with his arms outstretched. Saint Anthony mourned for him and wrapped him in the cloak. He wondered how he would bury the body, for he had not remembered to bring a shovel. Two lions came running from the wilderness and dug a grave with their claws.

Saint Anthony buried the holy Elder and took his garment of palm leaves, then he returned to his own monastery. Saint Anthony kept this garb as a precious inheritance, and wore it only twice a year, on Pascha and Pentecost.

Saint Paul of Thebes died in the year 341 when he was 113 years old. He did not establish a single monastery, but soon after his end there were many imitators of his life, and they filled the desert with monasteries. Saint Paul is honoured as the first desert-dweller and hermit.

In the twelfth century, Saint Paul’s relics were transferred to Constantinople and placed in the Peribleptos monastery of the Mother of God, on orders of the emperor Manuel (1143-1180). Later, they were taken to Venice, and finally to Hungary, at Ofa. Part of his head is in Rome.

Saint Paul of Thebes, whose Life was written by Saint Jerome, is not to be confused with Saint Paul the Simple (October 4).

Troparion — Tone 3

Inspired by the Spirit, / you were the first to dwell in the desert in emulation of Elijah the zealot; / as one who imitated the angels, you were made known to the world by Saint Anthony the Great. / Righteous Paul, entreat Christ God to grant us His great mercy.

Kontakion — Tone 3

Today we gather and praise you with hymns as an unwaning ray of the spiritual Sun; / for you shine on those in the darkness of ignorance, / leading all mankind to the heights, venerable Paul, / adornment of Thebes and firm foundation of the fathers and ascetics.

St John

From the West:

From Fr Alban Butler's Lives of the Saints

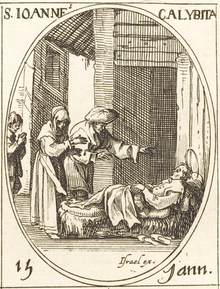

HE was the son of Eutropius, a rich nobleman in Constantinople. He secretly left home to become a monk among the Acæmetes. 1 After six years he returned disguised in the rags of a beggar, and subsisted by the charity of his parents, as a stranger, in a little hut near their house; hence he was called the Calybite. 2 He sanctified his soul by wonderful patience, meekness, humility, mortification, and prayer. He discovered himself to his mother, in his agony, in the year 450, and, according to his request, was buried under his hut; but his parents built over his tomb a stately church, as the author of his life mentions. Cedrenus, who says it stood in the western quarter of the city, calls it the church of poor John; 3 Zonaras, the church of St. John Calybite. 4 An old church, standing near the bridge of the isle of the Tiber in Rome, which bore his name, according to an inscription there, was built by Pope Formosus, (who died in 896,) together with an hospital. From which circumstance Du Cange 5 infers, that the body of our saint, which is preserved in this church, was conveyed from Constantinople to Rome, before the broaching of the Iconoclast heresy under Leo the Isarian, in 706: but his head remained at Constantinople till after that city fell into the hands of the Latins, in 1204; soon after which it was brought to Besanzon in Burgundy, where it is kept in St. Stephen’s church, with a Greek inscription round the case. The church which bears the name of Saint John Calybite, at Rome, with the hospital, is now in the hands of religious men of the order of St. John of God. According to a MS. life, commended by Baronius, St. John Calybite flourished under Theodosius the Younger, who died in 450: Nicephorus says, under Leo, who was proclaimed emperor in 457; so that both accounts may be true. On his genuine Greek acts, see Lambecius, Bibl. Vind. t. 8. p. 228. 395; Bollandus, p. 1035, gives his Latin acts the same which we find in Greek at St. Germain-des-Prez. See Montfaucon, Bibl. Coislianæ, p. 196. Bollandus adds other Latin acts, to which he gives the preference. See also Papebroch, Comm. ad Januarium Græcum metricum, t. 1. Maij. Jos. Assemani, in Calendaria Univ. ad 15 Jan. t. 6. p. 76. Chatelain, p. 283, &c. 1

Note 1. Papebroch supposes St. John Calybite to have made a long voyage at sea; but this circumstance seems to have no other foundation, than the mistake of those who place his birth at Rome, forgetting that Constantinople was then called New Rome. No mention is made of any long voyage in his genuine Greek acts, nor in the interpolated Latin. He sailed only three-score furlongs from Constantinople to the place called [Greek], and from the peaceful abode of the Acæmetes’ monks, ([Greek], or dwelling of peace,) opposite to Sosthenium on the Thracian shore, where the monastery of the Acæmetes stood. See Gyllius, and Jos. Assemani, in Calend. Univ. T. 6. p. 77. [back]

Note 2. From [Greek], a cottage, an hut. [back]

Note 3. Cedr. ad an. 461. [back]

Note 4. Zonaras, p. 41. [back]

Note 5. Du Cange, Constantinop. Christiana, l. 4. c. 6. n. 15. [back]

HE was the son of Eutropius, a rich nobleman in Constantinople. He secretly left home to become a monk among the Acæmetes. 1 After six years he returned disguised in the rags of a beggar, and subsisted by the charity of his parents, as a stranger, in a little hut near their house; hence he was called the Calybite. 2 He sanctified his soul by wonderful patience, meekness, humility, mortification, and prayer. He discovered himself to his mother, in his agony, in the year 450, and, according to his request, was buried under his hut; but his parents built over his tomb a stately church, as the author of his life mentions. Cedrenus, who says it stood in the western quarter of the city, calls it the church of poor John; 3 Zonaras, the church of St. John Calybite. 4 An old church, standing near the bridge of the isle of the Tiber in Rome, which bore his name, according to an inscription there, was built by Pope Formosus, (who died in 896,) together with an hospital. From which circumstance Du Cange 5 infers, that the body of our saint, which is preserved in this church, was conveyed from Constantinople to Rome, before the broaching of the Iconoclast heresy under Leo the Isarian, in 706: but his head remained at Constantinople till after that city fell into the hands of the Latins, in 1204; soon after which it was brought to Besanzon in Burgundy, where it is kept in St. Stephen’s church, with a Greek inscription round the case. The church which bears the name of Saint John Calybite, at Rome, with the hospital, is now in the hands of religious men of the order of St. John of God. According to a MS. life, commended by Baronius, St. John Calybite flourished under Theodosius the Younger, who died in 450: Nicephorus says, under Leo, who was proclaimed emperor in 457; so that both accounts may be true. On his genuine Greek acts, see Lambecius, Bibl. Vind. t. 8. p. 228. 395; Bollandus, p. 1035, gives his Latin acts the same which we find in Greek at St. Germain-des-Prez. See Montfaucon, Bibl. Coislianæ, p. 196. Bollandus adds other Latin acts, to which he gives the preference. See also Papebroch, Comm. ad Januarium Græcum metricum, t. 1. Maij. Jos. Assemani, in Calendaria Univ. ad 15 Jan. t. 6. p. 76. Chatelain, p. 283, &c. 1

Note 1. Papebroch supposes St. John Calybite to have made a long voyage at sea; but this circumstance seems to have no other foundation, than the mistake of those who place his birth at Rome, forgetting that Constantinople was then called New Rome. No mention is made of any long voyage in his genuine Greek acts, nor in the interpolated Latin. He sailed only three-score furlongs from Constantinople to the place called [Greek], and from the peaceful abode of the Acæmetes’ monks, ([Greek], or dwelling of peace,) opposite to Sosthenium on the Thracian shore, where the monastery of the Acæmetes stood. See Gyllius, and Jos. Assemani, in Calend. Univ. T. 6. p. 77. [back]

Note 2. From [Greek], a cottage, an hut. [back]

Note 3. Cedr. ad an. 461. [back]

Note 4. Zonaras, p. 41. [back]

Note 5. Du Cange, Constantinop. Christiana, l. 4. c. 6. n. 15. [back]

St John

From the East:

Saint John the Hut-Dweller was the son of rich and illustrious parents and was born in Constantinople in the early fifth century. He received a fine education, and he mastered rhetoric and philosophy by the age of twelve. He also loved to read spiritual books. Perceiving the vanity of worldly life, he chose the path that was narrow and extremely difficult. Filled with longing to enter a monastery, he confided his intention to a passing monk. John made him promise to come back for him when he returned from his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and take him to his monastery.

He asked his parents for a Gospel so that he might study the words of Christ. John’s parents hired a calligrapher to copy the text and had the volume bound in a golden cover studded with gems. John read the Gospel constantly, delighting in the Savior’s words.

The monk kept his promise to come back for John, and they went secretly to Bithynia. At the monastery of the “Unsleeping” (Akoimitoi), he received monastic tonsure. The young monk began his ascetical labours with zeal, astonishing the brethren with his unceasing prayer, humble obedience, strict abstinence, and perseverance at work.

After six years, he began to undergo temptations. He remembered his parents, how much they loved him, and what sorrow he caused them. He regretted leaving them and was filled with a burning desire to see them again.

Saint John explained his situation to the igumen Saint Marcellus (December 29) and he asked to be released from the monastery. He begged the igumen for his blessing and prayers to return home. He bid farewell to the brethren, hoping that by their prayers and with the help of God, he would both see his parents and overcome the snares of the devil. The igumen then blessed him for his journey.

Saint John returned to Constantinople, not to resume his former life of luxury, but dressed as a beggar, and unknown to anyone. He settled in a corner by the gates of his parents’ home. His father noticed the “pauper,” and began to send him food from his table, for the sake of Christ. John lived in a small hut for three years, oppressed and insulted by the servants, enduring cold and frost, unceasingly conversing with the Lord and the holy angels.

Before his death, the Lord appeared to the monk in a vision, revealing that the end of his sorrows was approaching and that in three days he would be taken into the Heavenly Kingdom. Therefore, he asked the steward to give his mother a message to come to him, for he had something to say to her.

At first, she did not wish to go, but she was curious to know what this beggar had to say to her. Then he sent her another message, saying that he would die in three days. John thanked her for the charity he had received and told her that God would reward her for it. He then made her promise to bury him beneath his hut, dressed in his rags. Only then did the saint give her his Gospel, which he always carried with him, saying, “May this console you in this life, and guide you to the next life.”

She showed the Gospel to her husband, saying that it was similar to the one they had given their son. He realized that it was, in fact, the very Gospel they had commissioned for John. They went back to the gates, intending to ask the pauper where he got the Gospel, and if he knew anything about their son. Unable to restrain himself any longer, he admitted that he was their child. With tears of joy, they embraced him, weeping because he had endured privation for so long at the very gates of his parental home.

The saint died in the mid-fifth century when he was not quite twenty-five years old. On the place of his burial, the parents built a church and beside it a hostel for strangers. When they died, they were buried in the church they had built.

In the twelfth century, the head of the saint was taken by Crusaders to Besançon (in France), and other relics of the saint were taken to Rome.

Troparion — Tone 4

From your early youth, / you longed with fervour for the things of the Lord. / Leaving the world and its pleasures, / you became an example of monastic life. / Most blessed John, you built your hut at the door of your parents’ house and overcame the devil’s guiles. / Therefore Christ Himself has worthily glorified you.

Kontakion — Tone 2

Longing for poverty in imitation of Christ, / you abandoned your parents’ wealth, wise Father John; / grasping the Gospel in your hands, / you followed Christ God, unceasingly praying for us all.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.