From Crisis

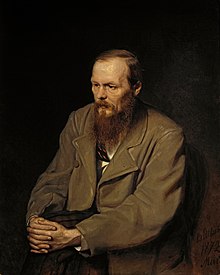

By Darrick Taylor, PhD

Dostoevsky wished to show how a Christian could overcome the powerful grip of modern ideas that denied the existence of God and spiritual realities more generally.

In the first part of this essay, I traced the outline of the life and career of Fyodor Dostoevsky, and I detailed how he pursued his struggle with modern ideas through the creation of his novels—in particular, how he created characters seemingly trapped by powerful but false beliefs that doomed them. In this second installment, we will see how Dostoevsky tried to answer these beliefs and discuss why his answers are not marred by his anti-Catholicism.

The Modern Christ Figure

Dostoevsky’s protagonists in the novels discussed so far, as well as those in his more autobiographical works, Notes from the House of the Dead and The Gambler, portray men and women infected with the modern intellectual diseases with which he believed his native Russia was infected. This is a key to understanding them. But he also wished to show how a Christian could overcome the powerful grip of modern ideas that denied the existence of God and spiritual realities more generally.

After his return from exile in 1859, he struggled to create a convincing psychological portrait of a person who did this, partly for creative reasons, partly political. In Notes from Underground, the Underground Man is presented as an unreliable narrator, uttering contradictory ideas, but Dostoevsky originally planned a conversion for him in the course of the story. But as he wrote to his brother, Russian political censors “cut the part where I deduced from all this the need for belief and for Christ” for political reasons.

The creative difficulties that faced Dostoevsky were the nature of modern man himself. In his view, the “Westernizers” he opposed in Russia misunderstood human nature (and God) because of their drive for self-realization and self-aggrandizement. Their rationalistic, Enlightenment ideas led them to separate themselves from the rest of humanity, and the promise of technical control over self, society, and world seemed to promise a utopian paradise apart from God, nature, tradition, or anything else.

Dostoevsky thought such promises were a dangerous illusion, but he knew personally their enormous power. For someone in thrall to them, the idea that the highest form of life is one of humility, meekness, and submission to God, is a monumental absurdity. How could one break the spell of those beliefs?

His first attempt to create a character who could be a “Christ figure” in the modern world was The Idiot, published in 1869. It tells the story of Prince Myshkin, an honest, decent, but troubled man who is bedeviled by epileptic fits (there is more than a little autobiography in this character, obviously). Myshkin returns from a stay at a sanatorium in Switzerland to find himself involved in a love triangle with two women.

But Myshkin, whom Dostoevsky called his “positively good and beautiful man,” is undone by Ganya, a ruthless and corrupt man who is also involved with the two women. In the end, Myshkin’s goodness and guile cannot overcome the moral turpitude of those around him, and the novel ends with Myshkin breaking down and returning to the sanatorium from which he initially returned. The most beautiful “Christ” figure in this story is no match for the emptiness and nihilism of modern society.

Dostoevsky’s crowning achievement would come in his last—and most would say greatest—novel, The Brothers Karamazov. In that work, he tells the story of a depraved landowner, Fyodor Karamazov, and his three sons, Dmitri, Ivan and Alyosha. The plot revolves around the murder of the old man and the enmity of his sons toward him, as suspicion alights on the eldest, Dmitri, who sparred with his father over his inheritance and a woman. Though he is convicted of the crime, the real drama, as usual in Dostoevsky, was between competing ideas, represented by the two younger brothers, Ivan and Alyosha.

Alyosha, as the novel begins, is a novice in a monastery, and Ivan, a materialist atheist. In order to beguile Alyosha, Ivan tells him of his beliefs in the form of a “poem” (a parable, really), the famous story of the “Grand Inquisitor.” In it, Ivan paints a picture of a 16th century Inquisitor who presents Dostoevsky’s final statement on modernity and the West: in Seville, Christ Himself returns to earth, and heals a dead girl, but the Inquisitor arrests and imprisons Him on sight. In a raging soliloquy, the Inquisitor condemns Christ for having given freedom to mankind, who cannot bear it but must be led by those who have instead chosen “to correct your [Christ] work.” Christ, who never says a word during this harangue, kisses the old Inquisitor on the lips before he orders him to leave, never to return.

Dostoevsky’s parable, put into the mouth of Ivan, the atheist intellectual, has dazzled critics ever since because it seemed to express the heart of the human predicament. But Dostoevsky did not intend Ivan’s message to be his own, and he worried that readers might take it that way. This is because in the novel, Alyosha, who is young, naïve, and no intellectual, is taken in somewhat by Ivan’s false dilemma, mainly out of love for his brother. Dostoevsky feared that readers would mistake Alyosha’s weakness for the author’s disapproval, but he did not put an opposite speech in Alyosha’s mouth because it would not be psychologically accurate. Instead, he placed his rebuttal to Ivan in the last testament of Alyosha’s spiritual mentor, the Elder Zosima.

In the chapter “The Russian Monk,” Dostoevsky has Zosima recall his young days as a soldier, and how he came to the monastery, as an illustration of where Ivan went wrong in his critique of Christianity. In Zosima’s tale, he contends that modern men like Ivan misunderstand human nature because they seek self-realization at the expense of others. For Dostoevsky, Ivan’s Inquisitor represents a type of dualistic thinking—the world must be governed by the rational control of the “elect” or suffer the violent anarchy of the many. There is pure innocence and pure depravity, nothing else. The only way out of this is to be detached, superior to the world and to others—to control them.

In his account of his life, Zosima, without explicitly saying so, confesses that he was once like Ivan: bent on self-aggrandizement and control of others. But through his personal struggle, he came to see this drive as the root of the problem. Modern men, through their obsession with rational control and the isolation of self from the rest of creation, have become “self-lacerated,” cut off from the source of their humanity in nature and God. Against the Samost of the Westernizers (meaning individual self-ownership, directed against others), Dostoevsky, through Zosima, counterpoises universal moral responsibility, rooted in mutual love, and the Russian ideal of Sobornost, a community of jointly living members formed by the Holy Spirit.

The Elder Zosima’s writings critique Ivan’s ideology by demonstrating the false asceticism that lies at the root of his vision. Segregating oneself from the world and other men only sublimates man’s natural inclination to prideful self-assertion. The genius of the critique is that this asceticism characterizes not only modern intellectuals and bureaucrats but also the revolutionaries who want to overthrow society—they are all trapped by this “self-lacerating” asceticism. What is required instead is a self-surrender to others—despite the pain of humiliation it requires—and ultimately to God. True asceticism is not an act of self-realization but of abnegation in the faith that one’s true self will be returned by the “other.”

Dostoevsky completes his critique through the events of the story, in which Ivan, whose isolation leads to a mental breakdown by its end, is contrasted with the child-like Alyosha, whose less intellectual but more open and loving nature outlasts the traumas of the Karamazov family. While Dmitri is forced to flee the country and Ivan must find a way to recover his sanity, the novel ends with Alyosha surrounded by school children cheering his name. (Dostoevsky wanted to write a children’s novel, and the choice of ending was apt, as children have little place in the imagination of “self-lacerated” technocrats.) Thus Dostoevsky, in his final, greatest work, created a character that exorcised the demons of his youth and embodied the truth of Christ in a psychologically modern setting realistically.

Dostoevsky’s Anti-Catholicism

The forgoing portrait of Dostoevsky’s work left to one side a question that must be addressed: his very deep-rooted anti-Catholicism. Enmity toward Rome is ancient in Russia, going back to the medieval and early modern periods and its many wars with the kingdom of Poland. Dostoevsky imbibed this enmity with his mother’s milk, and his firsthand experience reinforced these prejudices.

During his prison stay in Siberia, he observed the machinations of Polish prisoners, many of whom were revolutionaries hoping to throw off the Russian yoke (Russia, along with Prussia, had “partitioned” Poland in the late eighteenth century, dividing its territory between them). He found particularly repellent their loyalty to the Jesuits, whom Russians long regarded as treacherous foreign agents.

Unsurprisingly, contempt for the Catholic Church, Jesuits, and Poles features prominently in his writings, though more so in his journalism than his novels. Dostoevsky saw in the Catholic Church the spirit of the pagan Roman Empire, with its lust for power and control, debased into a spiritual unity predicated on force. One of his favorite sayings, which recurs in his both his fiction and nonfiction writing, is that Rome turned “the Church into the State.”

For him, all the ills of modern society could be blamed on Western materialism and greed, the result of its controlling religious idea, which came from Catholicism. His fable of the “Grand Inquisitor” presumes the truth of this idea: Dostoevsky believed socialism was the outcome of Roman Catholicism when its adherents lost their faith in God, as Ivan indicates in the novel.

Dostoevsky’s prejudices regarding Western Europe were typical of his “Slavophile” comrades in many respects, reinforced by several years of living in Western Europe while escaping his creditors. But his grasp of Catholic history and the origins of its malaise were, to say the least, rather tenuous. Moreover, contemporary Russian writers like Ivan Turgenev disagreed with his complete condemnation of Europe, pointing out the flaws in his position. They noted how much Dostoevsky admired Western art and literature, for example, and tasked him with being inconsistent. If Catholicism was responsible for everything that was evil in Western Europe, surely it must be responsible for the many things that Dostoevsky admired?

Dostoevsky contrasted the horror of Rome with a spiritualized ideal of Russian Orthodoxy (which, to be fair, he knew was an ideal), in which faith and unity were based on love not force. This faith was inextricably bound up with a very nineteenth-century nationalism, in which Russia played a providential role in leading the world back to Christ. Dostoevsky proclaimed in his Diary of a Writer that the Russian Orthodox Church would be the vehicle for the salvation of the world, and the great masses of Russian peasants, the source of the true faith, would be the salvation of Russia, overcoming the faithlessness of its elites. He wrote several letters in which he spoke of a “Russian Christ” at the heart of his thought. For Dostoevsky, Russian nationality and religion were linked, and rootless intellectuals, with no deep connection to their country, were of necessity atheists.

This identification of Christ and nationality is one that Catholics must reject as heresy. There is no denying this. A few things might be said in Dostoevsky’s defense, however. One is that he was hardly a theologian, and statements like these in his writings are not formal doctrinal statements. Another is that he was reacting to Russian activists who rejected Russian tradition entirely.

His position was not unlike that of Westerners today, in which similar activists insist on the total depravity of Western civilization (for being tainted with racism, sexism, etc.,) and that it is worthy of nothing but destruction. Dostoevsky needed to believe in the Russian people and their god before he could believe in Christ, the true God, in order to bypass the abstractions of modern thought, to go from the particulars of his life to a more universal faith in God. If he conflated the two, it is a sin common to those who love their country too passionately, something not unknown in the United States.

And it must be said that his novels are more encompassing on this point than his journalism. Though there are two significant outbursts against Rome in The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov, in general his novels touch on more personal and universal themes rather than strictly theological ones.

Whatever polemical statements he made, Dostoevsky was capable of greater openness in practice. He befriended Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900) at the end of his life, a philosopher and theologian who would enter communion with Rome in the 1880s. Some think the character of Alyosha was based on Solovyov. In any event, Catholics who wish to become mature believers should not let whatever errors Dostoevsky was guilty of prevent them from appreciating the work of a great artist.

Why Catholics (And Everyone Else) Should Read Dostoevsky

Why, then, should Catholics read Dostoevsky? In many respects, for the same reasons that everyone else should. Dostoevsky is one of the great masters of world literature, and an educated person ought to at least have read one of his novels to claim such education. His works will repay those who give them the time and attention they deserve, no matter what their beliefs, because of their keen psychological insight and ability to capture the complexities of human nature.

But more particularly, Dostoevsky can be a great aid to Catholics and even other people of faith (even if it is only faith in Western civilization) in the current state of things. He was the master storyteller of the absurd, the chronicler of what it feels like to keep faith with one’s ideals while being subject to the absurdities of modern life. Dostoevsky understood and was capable of portraying imaginatively the multifaceted nature of humanity, in all of its wonderful and horrifying aspects, perhaps more than any other author I have encountered.

Most especially pertinent to our times was his struggle with attraction to the Vsechlovek, the man without limits, and his ultimate triumph over this temptation. It perhaps doesn’t need reemphasizing that the modern age is a Faustian one, as seemingly every day we consign more of our lives over to our technological creations, so certain this will lead to happiness. Dostoevsky’s warning about the “self-laceration” such faith in technical control requires is a salutary one for believers and unbelievers alike in an age where our technology makes it tempting to abandon our humanity entirely.

For Christian believers, it is his very modern experience of doubt and faith regained that is most important. One of the siren calls of modern atheism is a historical one, probably best articulated by Friedrich Nietzsche. At one time, so the argument goes, Christianity served a purpose in society—built up institutions and cultural resources that were necessary for its growth. But now mankind has matured beyond its strictures, and it must die to make way for a new set of “values.” Others are more materialist in nature, denying the spiritual nature of man and the reality of his immortal soul. Dostoevsky’s genius shows us the near-sightedness and narrowness of such visions, and he allows us to see through the lens of his imagination that humanity can only truly flourish in a dehumanizing world if it bears the image of Christ.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.