'Dostoevsky represents one powerful reply to many of the cataclysmic changes that have swept modern Western civilization since the eighteenth century.'

By Darrick Taylor, PhD

Dostoevsky represents one powerful reply to many of the cataclysmic changes that have swept modern Western civilization since the eighteenth century.

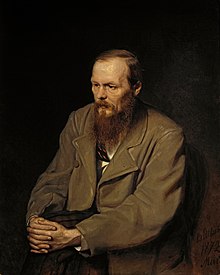

Few novelists have been feted with praise as much as the nineteenth-century Russian novelist Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-1881). Numerous intellectuals regarded him as the prophet of their age, quite literally. Albert Camus proclaimed Dostoevsky, not Karl Marx, the “prophet of the twentieth century.” The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche despised Christianity but admired the Orthodox Dostoevsky, saying he was “the only psychologist from whom I have anything to learn.”

Sigmund Freud called Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov “the most magnificent novel ever written.” Albert Einstein echoed Freud’s opinion, calling it “the most wonderful book I have ever laid my hands on” and that “Dostoevsky gives me more than any scientist, more than Gauss!” (He was referring to Carl Friedrich Gauss, a nineteenth century mathematician.)

The reason for such adulation has to do with Dostoevsky’s response to his own life and times. For these thinkers, facing the upheavals of the 20th century, Dostoevsky represents one powerful reply to many of the cataclysmic changes that have swept modern Western civilization since the eighteenth century. And it is one that Catholics could learn a great deal from. In what follows, I outline for those readers not familiar with his work why his literary response to the crises of modernity is so compelling.

A Modern Life and Times

Dostoevsky was born in Moscow in 1821, raised in a devout, middle-class household by his mother, whose faith influenced him, and his father, a physician. Born into a Russian Empire after the Napoleonic wars, racked by the influence of Revolutionary Western ideas—such ideas inspired a failed coup in December 1825 by Russian military officers against the Czar when he was four years old—Dostoevsky caught the spirit of that age as a young man.

Rejecting the career his father envisioned for him as a military engineer, he resigned his commission to become a writer in 1844. Finding success among critics with his first novel in 1846, he soon rejected his family’s Russian Orthodox faith and became an atheist. The next year, he fell in with a group of socialist thinkers called the Petrashevsky Circle, whose revolutionary schemes were mostly posturing. Dostoevsky would later satirize them in his writings.

The Czarist government took them seriously, however, and, in 1849, arrested the group, including Dostoevsky. After putting them into box cars and letting them sit for several days, the government sent them before a firing squad, only to have the sentence of execution commuted to imprisonment in Siberia at the last moment. In reality, the whole affair was manufactured to punish Dostoevsky and his friends and make an example out of them. It worked: two of his colleagues committed suicide after their commutation.

Dostoevsky spent the next eight years in Siberia, and the whole affair changed his life. While in prison, the middle-class Dostoevsky encountered Russian peasants for the first time, and he found the decency and faith of some of them deeply moving. While in prison, he began to reconnect with his Orthodox faith, even as he struggled with a new challenge, the epileptic fits that would plague him the rest of his days.

When he returned from Siberia in 1859, Dostoevsky proclaimed new allegiances both as a writer and a believer. No longer a partisan of the “Westernizers,” those Russian intellectuals who wanted to reform Russian society along Enlightenment-inspired, often socialist lines, he threw in his lot with the Slavophiles, those intellectuals who looked to the Russian Orthodox tradition as the cure for the country’s ills.

Identifying the Foe

For the next several decades of his life, in articles, journals, and above all in his novels, Dostoevsky worked out the contours of his faith, struggling against the ideas that had engendered his loss of faith and which haunted him until the last decade or so of his life.

For example, after he wrote his first novel, he fell under the influence of the Russian critic Vissarion Belinsky, who gave it high praise, and who was an admirer of Ludwig Feuerbach. Through Belinsky, Dostoevsky imbibed Feuerbach’s atheistic philosophy, which affected him all his life. To boil down Feuerbach’s idea, all statements about God are really projections of the human mind—they are really disguised statements about man.

According to Boyce Gibson, Dostoevsky was haunted by an idea from Russian literature called the Vsechelovek, the “all-man,” a Faustian figure who could encompass the whole of human experience, good and evil. Dostoevsky instinctively hated limits; as he wrote to one of his friends, “I have exceeded the limit all my life.” This fascination with the “all-man” was one he knew he could not sustain as a Christian, and his oeuvre is in some ways a working out of this struggle to escape the grip of his formative unbelief.

Dostoevsky’s ability to hold opposite ideas in tension and articulate them in unique, independent voices in his novels led the Soviet literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin to call them polyphonic, meaning they gave equal weight to clashing ideas. His Notes from Underground (1863) does this in the form of an inner dialogue of a tortured protagonist. In that novel, Dostoevsky took aim at the utopian claims of Western rationalism: the main character is poisoned by “self-consciousness” caused by the “rational egotism” of Liberal, utilitarian ideology.

The main character—the titular “Underground Man”—critiques the idea of social engineers making mankind happy via some mathematical calculus, embodied in the symbol of the “Crystal Palace.” Through this character, Dostoevsky attacked the work of Nikolay Chernyshevsky, a Russian “Westernizer” who epitomized everything that he hated about modern, Western civilization. More specifically, Notes from Underground critiques Russian Liberals of the 1830s and ’40s, whose naive idealism he blamed for the arrival of even worse ideologies (Marxism, anarchism, etc.) in the 1860s.

Dostoevsky parodied the idea of healthy, well-adjusted, Rationalist Man with the Underground Man, who was sick because of his obsession with ideas, a theme he would return to in later novels. He followed up Notes from Underground with Crime and Punishment in 1866, which centers on the university student Raskolnikov.

Raskolnikov is an intellectual who despises the shallow materialism of his age and conceives the idea that great men, individuals who rise above the common herd, must break conventional and natural laws in order to move society forward (with a nod toward Napoleon). To “prove” his idea, Raskolnikov decides to murder his landlady, to whom he owes money, since her life is worth less than his. But during the murder, his landlady’s sister walks in, and he is forced to kill her as well.

The rest of the novel, most of it in fact, deals with the psychological fallout from his actions and the efforts of a sympathetic police detective—who suspects he is guilty but cannot prove it—to convince him to confess to his crimes. In Raskolnikov, Dostoevsky began to perfect his devastating indictment of Russian Westernizers. Raskolnikov is the first of a long line of characters, sensitive and intelligent with a genuine if abstract desire for justice, whose commitment to utopian ideals lead them to commit horrible crimes in pursuit of them, or to set such in motion by their zeal.

The apotheosis of this comes in his 1871 political novel Demons, a work based on real life events. In 1869, a group of Russian anarchists murdered one of their own members on the orders of their leader, Sergey Nechayev. From this, Dostoevsky spun the tale of Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky and his son, Pyotr Stepanovich. Stepan Trofimovich is a liberal intellectual who lives in his own mind, full of lofty and noble sentiments but with precious little contact with reality.

He idolizes the Russian peasantry without ever having met one. He carries on a platonic romance with a wealthy widow without ever bringing it to fruition. Most importantly, he bears a son without actually raising him. He sends Pyotr Stepanovich off to Western Europe to a boarding school, and when Pyotr returns to the provincial town where his father lives, he is a fully radicalized revolutionary.

Pyotr Stepanovich creates a cell of revolutionaries in this provincial town and convinces them to murder one of their members (in imitation of Nechayev). By the novel’s end, they have literally set the town ablaze. Stepan Trofimovich begins only at the end to realize the damage his beliefs have caused, and in a fevered delirium, he wanders the Russian countryside looking to meet a real Russian peasant for the first time, seeking in him the face of Christ. Before he expires, he prophesies that Christ will one day cast out the demons that haunt his beloved Russia, and the people will lay at His feet like the Gadarene madman of the Gospels (hence the title of the work).

Dostoevsky is sometimes lauded as a prophet by anti-communists on the Right because he predicted the horrors of communism. Pyotr Stepanovich and his companion, Stavrogin, have sometimes been seen as anticipations of Stalin and Lenin, respectively. But Dostoevsky’s aim was much wider than this, for his target was not merely representatives of modern Western thought, such as socialism and communism, but the entire train of modern life that denied the reality of God and our transcendent destiny. His genius was his ability to incarnate both this trend and his own antidote for it in his novels.

In the next part of this essay, to be published next Saturday, I will discuss how Dostoevsky, having incarnated the problems he saw with modernity in his novels, attempted to resolve them through the creation of characters who would provide an answer to the challenge they presented to Christian faith. We will then discuss why, despite Dostoevsky’s very pronounced anti-Catholicism, Catholics should become readers of his work.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.