As His Eminence Francis, Cardinal George prophesied,

I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square. His successor will pick up the shards of a ruined society and slowly help rebuild civilization, as the church has done so often in human history.And as Hilaire Belloc said in the final paragraph of his Survivals and New Arrivals,

But if I be asked what sign we may look for to show that the advance of the Faith is at hand, I would answer by a word the modern world has forgotten: Persecution. When that shall once more be at work it will be morning.Remember, Tertullian, the third century theologian, said in his Apologeticus, 50, s. 13,

Plures efficimur, quoties metimur a vobis; semen est sanguis christianorum, 'We multiply whenever we are mown down by you; the blood of Christians is seed', or, as often quoted, ‘The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.'

The coming of persecution is the surest sign of ultimate victory!

From the Remnant

Running on funds supplied from their North American headquarters, as well as charity fundraisers and donations, the Sisters eventually established the Sacred Heart Orphanage, the Holy Infant Foundling Home, two schools and a leprosarium, with two freshwater wells and electricity.

Situated outside the city, the mission’s buildings, with the crèche atop a small hill, were spacious and well-ventilated with large windows, all made possible with philanthropic gifts from Boon-Haw Aw (1882-1954), renowned as the Tiger Balm King. All children had their own beds, all babies had their own cribs and all slept covered with their own mosquito netting.

With 60 babies below 1 year old, 33 between the ages of 2 and 5, and 34 between 5 and 18, to ensure all infants had proper attentive care, the nuns set up a system where eight of the older teenage girls were designated as little mothers. Each took care of a brood of five babies.

At the end of World War II, when aid was being distributed by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, Western doctors and nurses thoroughly inspected the grounds and commended the nuns on their efficiency and the overall cleanliness of the facilities. The kitchen was spotless, and all formula and bottles were sterilized.

After the Communists had completed their investigation, the nuns asked if they should continue their work. Not only were they praised for their service, but they were encouraged to go on as before. So the nuns resumed their daily duties, as permitted and urged by authorities.

However, subsequently, each of the orphans was ordered to police headquarters, where they were photographed for official records and questioned endlessly while authorities tried, unsuccessfully, to coerce the children to make accusations against the Sisters.

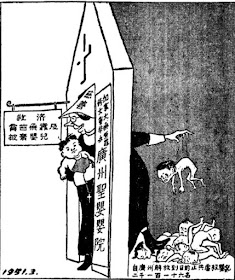

And then on February 7, 1951, the Sisters found themselves under attack in the newspapers. The Communists accused the women of being responsible for all 2,116 deaths of the babies, even those who had arrived at death’s door.

The first attack was followed by another, on February 28, 1951, when the regime’s newspapers published an editorial that eviscerated the Sisters. In part, it read:

“This orphanage, opened in 1933 with money from international Catholic organizations, symbolizes the hypocrite mask of the imperialists in their consistent plot of waging aggression under the pretext of charity work. Let’s deliver our next generation from the hand of those swindlers who have charitable faces and snake-like hearts!”

The anti-Catholic propaganda editorial agitated the masses. Newspapers printed letters, supposedly from outraged readers who demanded that authorities investigate and punish the imperialists. Alongside the letters ran lurid newspaper stories with exaggerated accounts that were more fiction than fact: that the nuns lived in luxury, that the orphans were treated less than human, that the Sisters plucked eyeballs from the orphans to make traditional Chinese medicine, and that the orphanages were slaughterhouses.

On March 1, 1951, at 2 in the afternoon, as part of the orchestrated theatrics of outrage, about 30 officers entered the mission and summoned Lo-Sail Chan, one of the older orphans, who had been entrusted with the management of the orphanage after the People’s Government decreed that institutions run by foreigners must appoint Chinese directors.

“I am responsible for everything here, not the Sisters,” Lo-Sail said.

“As far as the direction and administration of the house goes, well and good, as to the great number of dead infants, the Sisters alone are responsible,” the soldier said.

One of the officers stood in the orphanage and read a formal decree of confiscation: “The People’s Government, aware of the mismanagement of the Foundling Home operated by the Sisters, orders them to turn the establishment over to the government, which will immediately assume the direction of this work.”

Hearing that the facility was to be taken over, the children, many who never knew a home outside the orphanage, screamed and cried so loudly that the reading had to be stopped twice.

“You children are not grateful to the People’s Government for assuming control of your care!” the authority scolded.

A Party doctor examined the orphans. Disgusted that some of the children were ill and covered with lesions, he expressed that they were not worth the effort to save their lives, for surely they would die.

One of the older orphan girls spoke out.

“We would have died, too, when we came in like that, if it hadn’t been for the care of the Sisters!” she exclaimed.

Lo-Sail requested of the head officer, “If you wish to assume the direction of the work, we cannot resist you. There is, however, one request we want to make: Leave us the Sisters, who have brought us up as real mothers.”

“Your request is quite reasonable. The Sisters will remain with you,” the officer said.

Although accused of being responsible for the deaths of babies, the devastated nuns were ordered to remain in their convent and continue with their duties until the orphanage would be officially taken over by the Communists.

One of the authorities asked some of the older girls what they would do when the People’s Government would assume control.

“We will work hard and keep the Foundling Home going until the Sisters return,” they answered.

On the morning of March 12, 1951, three of the Sisters received permission to leave the premises, to attend Mass, but were called back as soon as they stepped outside.

“Something important will happen today, so you had better remain here,” a guard told them.

At 1 in the afternoon, four policemen and one policewoman from Central Bureau arrived at the mission and ordered the children to congregate in the refectory.

Sensing doom, Lo-Sail ordered the children not to gather in the refectory, but rather to meet in the sewing room, next to the Sisters’ quarters, where they heard authorities order Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur and Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine to follow them to headquarters.

“Oh, no! The Sisters are being taken from us!” cried the orphans as they ran to the nuns and clung to them as the authorities pried them off and pushed them back until the arresting party was through the exit gate, with it closed and locked behind them.

But the wailing of the orphans continued as the nuns walked away. In the distance Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur turned and defiantly waved her rosary, before one of her escorts violently shoved her along.

The two women had left behind on their beds scapulars, medals, passports and money, which their consoeurs found and put away, as they packed up blankets, towels, soap and other toiletries to take to their imprisoned Sisters.

The newly appointed Communist director of the orphanage stayed behind and was confronted by the orphans.

“You are forever telling us that you represent the People. We are the People! We are the victims of your underhanded schemes,” cried the children. “If you don’t believe the Sisters, believe us. You despise us, because we are orphans, but the Sisters loved us and took motherly care of us! We want the Sisters! Give us the Sisters!”

The director tried to assure them that the nuns would soon return, that they were merely going away for questioning.

“Lies! Lies! You have taken the Sisters to prison, and we know all about it. Don’t try to fool us into believing your deceitful words. The Sisters have no bedding in prison, and they will be sick.”

“The prisoners have all they need. Go back to your quarters.”

The next day, March 13, at noon, again four policemen and one policewoman arrived, locked the orphans in one common room and guarded the door.

In another room, the policewoman ordered three nuns to remove their rosary beads and crucifixes, as one of the policemen yelled through the closed door for them to hurry up. Pushed out of their room, the nuns were escorted through the building, as the children screamed and cried, silenced only when one of the policemen pounded threateningly on their door.

And then they were gone, walking down Wai San Road to prison.

The five nuns arrested over the two days were:

Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur (born Antoinette Couvrette, 1912-98, Sainte-Dorothée, County de Laval, Quebec) had been appointed superior of the orphanage four years earlier, after she arrived directly from Canada;

Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine (born Germaine Gravel, 1907-98, Saint-Prosper, County de Champlain, Quebec), the assistant superior, had arrived only months before the Communist armies. Previously, she spent 14 years in mission dispensary work in Manchuria, followed by one year in Shanghai, where she trained in pediatrics;

Sister Sainte-Foy (born Élisabeth Lemire, 1909-87, Baie-du-Febvre, County de Yamaska, Quebec) had been in Canton since before the routing of the Nationalist troops that abandoned the city in anticipation of the attack and invasion by the Japanese army, in October 1939. Her first assignment was to help take care of the abandoned 730 inmates in the Municipal Insane Asylum;

Sister Saint-Germain (born Imelda Laperrière, 1907-98, Pont-Rouge, County de Portneuf, Quebec) had arrived in Canton three months before the Communists “liberated” the city. Previously, she spent 12 years taking care of unwanted babies on Chung Ming Island (old form of Chongming), near Shanghai;

And Sister Saint-Victor (born Germaine Tanguay, 1907-77, Acton-Vale, County de Bagot, Quebec), had arrived in Canton, in 1948, and was placed in charge of material management of the orphanage. Previously, she spent 14 years in missionary work in Soochow, Kiangsu province (old forms of Suzhou, Jiangsu).

After the arrests, the Chinese People’s Relief Committee took complete physical control of the facilities, and, on March 26, the children were forced out of the orphanage to make room for authorities to move in, seemingly, the plan all along.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are subject to deletion if they are not germane. I have no problem with a bit of colourful language, but blasphemy or depraved profanity will not be allowed. Attacks on the Catholic Faith will not be tolerated. Comments will be deleted that are republican (Yanks! Note the lower case 'r'!), attacks on the legitimacy of Pope Leo XIV as the Vicar of Christ, the legitimacy of the House of Windsor or of the claims of the Elder Line of the House of France, or attacks on the legitimacy of any of the currently ruling Houses of Europe.