This was published prior to 1955 when Pius XII introduced today's Feast of St Joseph the Worker to counteract the Communist's International Labour Day/May Day. Ss Phil & James are now kept on the 11th.

Chartres

Church light-filled! stretto-spires heavenward flying

To greet God, Maker, Master, Harmony

Of souls; Church truth-belov’d, deceit-denying,

Inflamed with amorous divinity:

To greet God, Maker, Master, Harmony

Of souls; Church truth-belov’d, deceit-denying,

Inflamed with amorous divinity:

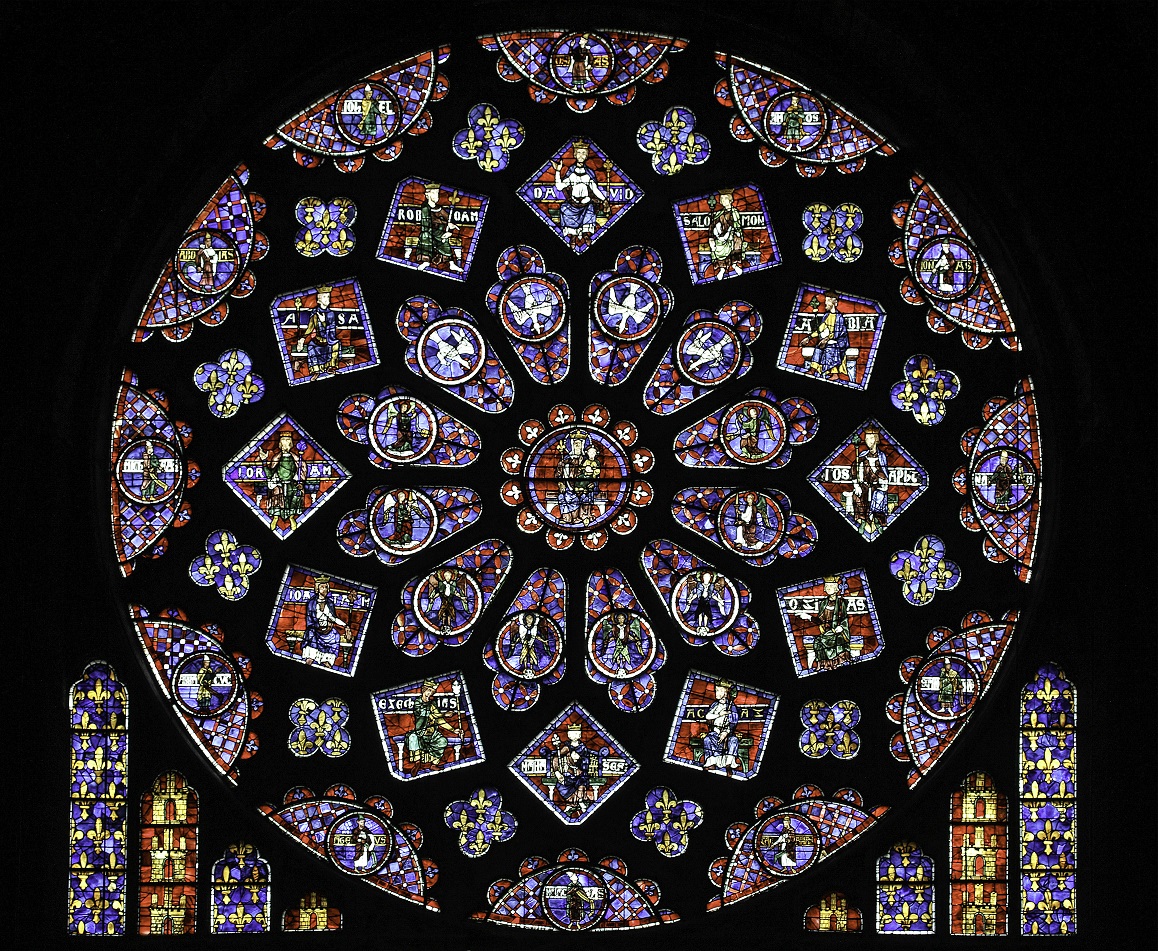

O mighty Chartres (in glass a thousand tales

Beyond world’s ends), stone bends to supplicate

The faithful Virgin, whom our prayer assails

Meek, confident. “I bid thee, hurl this weight

Beyond world’s ends), stone bends to supplicate

The faithful Virgin, whom our prayer assails

Meek, confident. “I bid thee, hurl this weight

Of sin into the sea, a mountain planted

Deep.” Thus the villager; thus lord and king,

All men, athirst for light, contritely panted,

Pilgrims laved and fed at grace’s spring.

Deep.” Thus the villager; thus lord and king,

All men, athirst for light, contritely panted,

Pilgrims laved and fed at grace’s spring.

O Virgin, glass-beheld, in sculpture fair,

I beg thee: Hear with living ears my prayer.

I beg thee: Hear with living ears my prayer.

I wrote a poem in high school about Chartres cathedral not because I had already been there or had immediate prospects of visiting, but because I had just finished reading Henry Adams’ Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, in which a cultivated agnostic gushes his enthusiasm for medieval Catholic France. The most famous chapter is entitled “The Virgin and the Dynamo”: a contrast between the Queen of Heaven whose devotees at Chartres built her a marvelous shrine full of radiance, and the impersonal forty-foot electrical generator that Adams beheld at the Great Exposition in Paris in 1900, symbol of a mechanistic, industrialized civilization.

This contrast invites us to consider the two aspects from which technology can be evaluated: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative superiority means, for example, being able to lift a larger number of heavier objects faster, or being able to produce more books more quickly. Qualitative superiority means being able to craft a beautiful object such as a statue, a stained-glass window, or an illuminated manuscript, even if it takes a very long time and the objects are comparatively few in number. This distinction being made, it is easy to draw the conclusion that medieval technology was superior to modern in a qualitative sense, while modern technology is superior to medieval only in a quantitative sense. In the end, which is the more important of the two?

“In the modern world of measurements,” writes Andrew Gushurst-Moore, “success is defined in physical terms, by that which is faster, bigger, taller—the celebration of power.”[1] One is reminded of the difference between the ancient Roman lectionary still contained in the Tridentine missal, as perfectly suited for its purpose as a slender Gothic column, and the modern multi-volume lectionary used for the Novus Ordo, a heaped-up pile of Soviet-style apartment blocs.

In 2015, I finally made it to Chartres. I was not among those jolly, singing, flag-bearing strong souls who make the trek by foot through mud and rain on the famous pilgrimage from Paris to Chartres—one might say, from the Dynamo to the Virgin. The grace of this visitation came rather during a father-son trip made while I was on sabbatical.

My son and I arrived at the sleepy medieval town on a train from Paris. Given our limited time, we had had to make a difficult choice: visit St. Denis, the first of Gothic churches, or Chartres, the finest of them. St. Thérèse’s “I choose all!” strategy was not going to work in this situation. We agreed on Chartres, the very name of which is like sweet mead or glistening water.

When I first caught sight of the spires, my heart began to race. As we drew near, I fell in love with her face, which I knew was no mere façade but an earnest of more within, as in the verse omnis gloria eius filiae regis ab intus (Ps 44:14). And when we entered, and my eyes had adjusted to the soothing half-light, I was transported out of myself and did not return to my shoes for a long time: my mind was soaring elsewhere, my eyes lost in dizzying vaults and shimmering glass. I do not know how to describe my feelings, except to say with Dionysius the Areopagite: it was no mere learning of divine things, but a suffering of them.

After we had left, I wrote the following in my journal.

* * *

October 1. Chartres Cathedral is, indeed, “a miracle in stone and glass.” I have never seen a church more beautiful than this. Nothing in Rome can even begin to compare with it. It utterly lacks the pomposity, worldliness, self-importance, and humanistic vanity of the Renaissance structures of Italy, the self-conscious triumphalism of the Counter-Reformation Baroque. It is grand but always turned heavenwards—and turning one’s soul heavenwards. There is deep humility and prayer built into, nay fused with, this immensely impressive edifice. Everywhere God is glorified in His saints, in the light that pours through the windows, ever shifting as the day proceeds, in the colors, the eyes, the sculptures… I said to J.: it is nothing less than the Bible in glass and stone. To say that medievals who could understand these images were “illiterates” would be to say that moderns who cannot are idiots.

Baroque art stresses God become man, heaven penetrating into this world—in the sacraments, the Eucharist, the priesthood, the Church visible as a body. It is deliberately sensual, bodily, plastic, dramatic. Gothic speaks rather of man aspiring to God, earth being lifted up to heaven, the ascent of the soul via Christ to God. It is straining to leave the body, to let the light suffuse and transfigure everything visible so that it might shine with intimations of divinity and immortality. The light-colored stone works together with the great height and the exquisite windows to create an effect of weightless uplift: Sursum corda.

It is not so much dramatic as symbolic—more prayer than propaganda. It delivers its message with the existential shock of beauty. But how many are receptive to this shock anymore? Sure, every visitor can say: “It’s lovely” or “it’s amazing,” but does it have a deep and lasting impact on them? In these times, when everyone’s eyes are glued to smartphones, when their ears are stuffed with earbuds, the words of Jesus take on a pitiful sound: “He who has ears to hear, let him hear; he who has eyes to see, let him see.”

Nothing we have done in architecture could even compare with Chartres, let alone equal it or surpass it. Built by people with so little technology compared to ours! But they had faith, vision, wonder, ambition, and the desire to give God the greatest and best. Yet moderns are arrogant, and put down the Middle Ages. This shows how blind we really are (or have become).

October 2. Low Mass [at Église Saint-Eugène-Sainte-Cécile in Paris] for the feast of the Guardian Angels was beautiful—so comforting to have the same Mass, the true Mass, the only real Mass of the Catholic Church—the same everywhere in the world. J. said: “Let’s light a candle for the restoration of tradition.” So we lit two, at a side altar of St. Anthony. My prayer was: “Lord, may the Church’s youth be renewed like the eagle’s.”

* * *

The visit to Chartres changed my life. I was reduced to dust before a theophany of absolute meaning. With a colossal immediacy and certitude, I apprehended the truth, in a way both intuitive and visceral, that high medieval Catholic culture was not merely one among many flowerings of the Christian Faith; it was the quintessential epiphany of what John Henry Newman called the “Idea” of Christianity—it was its imperfectible cultural embodiment, exhibiting a sublime conformity of thought and thing, ideal and incarnation, belief and building, aspiration and aesthetic, the likes of which the world had never seen before and has never seen since.

Chartres Cathedral was finished exactly 800 years ago, in the year 1220, four years before the birth of St. Thomas Aquinas in Roccasecca, and six years before the death of St. Francis in Assisi. It came from the age that gave us the most radical imitator of Christ and first stigmatist, who unleashed a revolution very different from feverish dreams of liberté, égalité, fraternité. It came from the era that gave us the greatest theologian of the Western Church, the Angelic Doctor, still the exemplary teacher and disciple of the harmony of faith and reason.

I had already been a traditionalist and an integralist for many years—theoretically. The experience of the cathedral shattered the last psychological remnants of nominalism, rationalism, liberalism, and every other -ism that lurks in the dingy shadows of modernity. I could see, hear, smell, taste, and touch the glory of Christendom—even at a distance of so many centuries. It was a consoling sight, an invigorating melody, a captivating smell, a heavenly taste, a healing touch. It roused awake the sensus fidei, the sensus catholicus in my soul. Somehow—I think for the first time—I had an overwhelming sense of the humble glory of being Catholic.[2]

The experience was a turning point, too, in my thinking about the liturgy. Prior to this, I had been willing to entertain the “reform of the reform” as a possibility; I played my part in adding smells and bells to the modern papal rite of Paul VI. Afterwards, I felt it was nothing but vanity and vexation of spirit, as if one had been asked to reconstruct Chartres with Lego bricks.

Visiting the cathedral with me that October 1st, my son was similarly overwhelmed. He said: “If I tried to describe this place to someone who had never been here, he wouldn’t believe me. He would think I was exaggerating, making stuff up. And then… you wouldn’t actually be able to find the right words anyway.”

Isn’t this the experience so many of us have with the traditional Latin Mass, when we try to talk about it with others, when we try to get them interested in their own heritage and birthright—in the words of Fr. Faber, “the most beautiful thing this side of heaven”?

Once a year, thanks to the Chartres pilgrimage, this silent, patient house of God resounds again in melodious chant, as the great Roman Pontifical Mass is celebrated at the high altar—that liturgy for which this building and thousands of others of similar ambition were built, and without which they seem absurdly overdone: gigantic relics we no longer know how to venerate, embarrassments in a world of comfort, efficiency, and sensible mediocrity.[3]

This miracle of a cathedral was almost destroyed with explosives at the time of the French Revolution, during the Reign of Terror (September 1793 to July 1794). It was spared, apparently, only when a local architect pointed out how much trouble it would be to clean up the vast amount of rubble.[4] For many years it lay idle and vacant, one of countless “Temples of Reason” proclaimed by the Revolution, with no Holy Sacrifice offered on its altars.

A far more subtle (though no less effective) cancellation of its raison d’être occurred less than two centuries later when Paul VI made the liturgy itself into a temple of reason and extinguished the mystical flame of Catholic worship. To our everlasting shame, it was not radical Jacobins but surpliced churchmen who undertook the more barbaric work of destroying the traditional Mass that constitutes the single greatest work of art in the Christian West—greater, by far, even than the Gothic church architecture of France, for it was nothing less than this “work of God” that inspired everything else surrounding it. A German author, Karl Lechner, observed:

Out of the Mass, among other things, the most profound splendor and ingenious fullness of the Catholic Church’s architectural style has grown ... Only on account of this worship can the proud majesty of a Gothic cathedral be understood. ... But Romanesque architecture, too, has its necessary requirement in the service of the Mass. ... Without the High Mass, no master builder of the spirited Middle Ages would have developed the basilica to this sublime, serious, and magnificent style. Without the Catholic service, neither Raphael nor Fra Angelico, Hubert van Eyck nor the younger Holbein, nor Lorenzo Ghiberti, Veit Stoss, and Peter Vischer would have brought to light the wonders of their brush and chisel, and adorned the Church of God on earth with a wealth of holy beauty that will remain a gem for all ages.[5]

The Mass of which Lechner wrote in 1877 was, of course, the Tridentine rite. The Novus Ordo could never have inspired Romanesque or Gothic architecture. This inspiration came from the Romano-Gallican liturgy of the Middle Ages, suffused with Carolingian “court ritual” and demanding for its setting a house of gold and silver worthy of such a dazzling jewel.

The movement for liturgical reform after World War II was driven by a number of principles, not all of them compatible with each other. But practically speaking, there was broad agreement about this one thing: that which was medieval had, by and large, to be expunged. It lacked the supposed domesticity and familiarity of the early Church—so it was said; in reality this meant it did not accord with the sterile Cartesian ideals of simplicity and clarity inherited from the same Enlightenment rationalism that gave us the French Revolution. The liturgical reformers, like their precursors at the Synod of Pistoia (1786), and their precursors in the Protestant revolt, viewed the medieval period as an age of extravagant superstition, speculation without scholarship, fanciful mysticism, remote otherworldliness. In the name of Modernity and its Progress, medieval liturgy, medieval chant and architecture and theology (scholasticism) had to be purged from the bloodstream, or, if they could not be purged, “renewed” or “renovated.”

To an extent far greater than the ultramontanism so beloved to neoscholasticism would ever have allowed possible, the renovating churchmen succeeded in demedievalizing Catholicism on earth, which was like tearing off the healthiest, most well-developed limbs of a great oak tree. The genius that built Chartres, the genius that had perfected our liturgy and its music, was exterminated. The modern liturgy is a ghostly, bloodless abstraction compared to the richly-textured traditional liturgy that appeals to every sense in a delicate lifelong courtship and raises the mind to the God beyond all, whose Word became flesh for us men and for our salvation.

Can we be so arrogant that we believe modernity represents progress? Progress over the masterpiece tradition gives us? We are like pygmies next to giants. The only sensible thing for moderns to do would be to sit like little children in the schoolroom of medieval Christendom, becoming lifelong apprentices in its workshop of wisdom and beauty, with the hope of someday acquiring a sliver of its mastery, with, perhaps, a renaissance to follow after several generations.

One cannot help thinking of the eloquent “Agatha Christie” petition of 1971, signed by 56 cultural figures in England, many of them not Catholic, and presented by Cardinal Heenan to Pope Paul VI:

If some senseless decree were to order the total or partial destruction of basilicas or cathedrals, then obviously it would be the educated—whatever their personal beliefs—who would rise up in horror to oppose such a possibility. Now the fact is that basilicas and cathedrals were built so as to celebrate a rite which, until a few months ago, constituted a living tradition. We are referring to the Roman Catholic Mass. Yet, according to the latest information in Rome, there is a plan to obliterate that Mass by the end of the current year.One of the axioms of contemporary publicity, religious as well as secular, is that modern man in general, and intellectuals in particular, have become intolerant of all forms of tradition and are anxious to suppress them and put something else in their place. But, like many other affirmations of our publicity machines, this axiom is false. Today, as in times gone by, educated people are in the vanguard where recognition of the value of tradition in concerned, and are the first to raise the alarm when it is threatened.We are not at this moment considering the religious or spiritual experience of millions of individuals. The rite in question, in its magnificent Latin text, has also inspired a host of priceless achievements in the arts—not only mystical works, but works by poets, philosophers, musicians, architects, painters and sculptors in all countries and epochs. Thus, it belongs to universal culture as well as to churchmen and formal Christians. In the materialistic and technocratic civilization that is increasingly threatening the life of mind and spirit in its original creative expression—the word—it seems particularly inhuman to deprive man of word-forms in one of their most grandiose manifestations.

In conclusion, the signatories say that “they wish to call to the attention of the Holy See, the appalling responsibility it would incur in the history of the human spirit were it to refuse to allow the Traditional Mass to survive.”[6] Why appalling? Gushurst-Moore suggests a reason: “The great books of literature, history, science, mathematics, or other subjects, and the great works in the history of art or music, are very much akin to religion and faith in revealing the face of God.”[7]

One can understand why the drafter of the petition might have subscribed to the pious myth that the Holy See is capable of “refusing to allow the Traditional Mass to survive.” Today, we are in a better position to see what Agatha Christie and her cosignatories could not. As Pope Benedict XVI lucidly declared, the liturgical tradition of the Catholic Church does not need a pope’s permission to exist or to continue to exist. The classical Roman Rite is a monument of tradition that can never be abolished, abrogated, or abandoned. The Holy Spirit Who formed this rite in the womb of Holy Mother Church would never allow such a betrayal, nor would the devoted children of that same Mother tolerate it. Cathedrals may rise and fall, revolutions ignite and subside, but this divine worship will endure until the Parousia.

The Traditional Mass survives not by the sufferance of its overlords but by the ever-renewed love of the little ones in Christ, who, however unworthy, join centuries of pilgrims to Chartres, to the Virgin, and to the Mass, threefold image of a single heavenly Jerusalem.

______________

[1] Glory in All Things: St Benedict and Catholic Education Today (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2019), 14.

[2] As a philosopher by training, I try to avoid “the sticky temptations of poetry.” Claims about “seeing the whole picture all at once” sound grandiose, hyperbolic, subjective, indemonstrable. But the philosopher is committed to describing reality as it is—and that includes the totality of one’s experience of it, however mundane or transcendent it may be.

[3] The embarrassment and incapacity extend beyond architecture to the realm of sacred music. Indeed, according to the most recent ecumenical council, “the musical tradition of the universal Church is a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, n. 112)—an astonishing claim to think about when you are standing in front of or inside of Chartres cathedral. The reason given? This music, above all Gregorian chant, is the sacred liturgy; not a mere add-on, but bone and flesh of the thing itself, in a way that no building could ever be. Yet that means the music stands or falls with the liturgical rite. If the rite and its music are perfect for each other, they create a sonic temple that harmonizes with the visual temple. All the traditional art forms cohere in the liturgy that stands at their center. There was a mighty battle over the wording of Sacrosanctum Concilium Chapter VI, on sacred music. Msgr. Johannes Overath won the battle, but lost the war: after the Council, this chapter was more or less ignored by all who implemented the conciliar constitution, with Paul VI leading them in his hand-wringing eulogy for Latin and Gregorian chant.

[4] See the account given at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chartres_Cathedral, where many good photographs of the cathedral are also to be found.

[5] K. Lechler, Die Confessionen in ihrem Verhältnisse zu Christus (Heilbronn: Verlag Gebr. Henninger, 1877), 166f., cited by Michael Fiedrowicz in a forthcoming book from Angelico Press.

[6] For the text and annotated list of signatories, see Joseph Shaw (ed.), The Case for Liturgical Restoration. Una Voce Studies on the Traditional Latin Mass (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2019), 213–16.

[7] Glory in All Things, 121.